Mikhail Vrubel Biography

Mikhail Alexandrovich Vrubel (1865-1910) was a Russian artist of remarkable talent and a turbulent. His paintings were produced in a political climate that was alternately hostile and sympathetic. In his lifetime, he knew both praise and disdain, with critics calling his work everything from “wild ugliness” to “the fascinating symphonies of a genius”. Gradually, however, Vrubel’s painting came to be viewed as an integral part of Russian culture. Some modern scholars compare his work directly to Early Renaissance or Late Byzantine art and recognize Vrubel as a proud artistic individual who held aloof from contemporary trends. Others consider Vrubel the founder of Russian Art Nouveau and group him with that movement.

Born into the family of a military lawyer, Vrubel graduated St. Petersburg University (in 1880) with a law degree, but entered the Academy of Arts the very same year. In his autobiography, written in 1901, Vrubel referred to his Academy years as the happiest in his life as an artist. For that he was indebted to professor Pavel Tchistyakov, who was famous for his method of teaching painting and drawing. Among Tchistyakov’s pupils were such outstanding painters as Vasily Surikov, Viktor Vasnetsov and Vasily Polenov who all thought very highly of their teacher. Vrubel owed much to the Academy and never shared the distaste towards it felt by many prominent painters of the time. Vrubel’s art, academic in a sense, was based on the cult of the model and drawing. His Academy drawings on classical subjects are striking for their elegant workmanship.

However, even during his training, Vrubel never was a devoted follower of the Academy style. Along with an expressiveness and rich imagination, his works already reveal a taste for improvisation, fragmentary composition, his characteristic “unfinished” manner peculiarly fused with classical style and monumentality. In 1884, the famous art historian Adrian Prakhov, who supervised the re-construction of the old and construction of the new cathedrals in Kiev, invited Vrubel to take part in the restoration of the Old Russian murals and mosaics in the 12th century Church of St. Cyril. The knowledge Vrubel acquired in the process of this work contributed to the development of his style as a painter. In St. Cyril’s Church, Vrubel executed new murals in place of the lost ones, The Descent of the Holy Spirit upon the Apostles (Pentecost) and Three Angels over the Body of Christ. Later, he was commissioned to paint icons for the iconostasis of the church, which he did in Venice where he spent several months in the years 1884-85. In Venice, Vrubel was particularly impressed by the medieval mosaics in the Church of San Marco and the Early Renaissance paintings of Giovanni Bellini and Cima da Conegliano. It was in Venice that Vrubel’s palette acquired strong saturated tones resembling the iridescent play of precious stones. While there, Vrubel produced four large icons, including The Virgin. He drew the face of the Virgin from the studies of E. Prakhova, wife of A. Prakhov.

Back in Kiev, Vrubel started a series of watercolor studies for the recently built Cathedral of St. Vladimir, among them several versions of The Lamentation (1887) and The Resurrection (1887). However, the jury rejected all his projects. In Kiev, Vrubel started to work on the first version of The Demon, an illustration to Mikhail Lermontov's 1890 poem of the same name. The Kiev versions of The Demon, both the pictures and sculptures, have not survived. In fact, Vrubel rarely took pains to preserve his works, being more interested in the process of creation than in the result.

Other works of the Kiev period include the large canvas Portrait of a Girl against a Persian Carpet and The Oriental Tale (1886), the latter inspired by The Arabian Nights, Hamlet and Ophelia (1884) and numerous watercolors with flowers. The murals, canvases, or small watercolors done in Kiev have none of the Art Nouveau style, which was to appear only in Vrubel’s works of the Moscow period.

Vrubel initially planned to stop in Moscow for a few days during a business trip, but circumstances and his acquaintances from Moscow's art world kept him in the city for years. During his first year in Moscow, Vrubel went on working on the paintings he had started in Kiev. Among others are a series of Demon paintings, including The Seated Demon (1890) and illustrations to Lermontov's novel A Hero of Our Time (1890-1891). These illustrations made his name known to the public but brought him notoriety rather than fame: too unusual for the tastes of 1880s, they caused bewilderment and derision. Russian artistic circles, however, received Vrubel favorably. He found support from Savva Mamontov, a famous Moscow patron of arts, who invited the artist to work at the pottery shop on his estate in Abramtsevo near Moscow and commissioned him to paint the scenery for his Private Opera in Moscow. Mamontov also recommended Vrubel to his friends, and quite soon the painter had a number of commissions for decorative work at their mansions. Together with Mamontov and his family Vrubel traveled throughout Europe.

Vrubel tried himself in various artistic media, including applied art (ceramics, majolica, stained glass), architectural masks, stage set and costume design, and even architecture. His talent showed in everything he did, and he did almost everything in the search for a lucid beautiful style. This search eventually culminated in the founding of the Russian Art Nouveau.

With its roots in Russian Neo-Romanticism, the most characteristic feature of this style is its cult of beauty – melancholic, enigmatic and refined – and its tendency to the synthesis of arts in everything, be it an illustrated book, a theater performance, or décor. Art Nouveau was never confined to easel painting or sculpture alone. It found its way into people’s houses becoming an essential part of interior decoration and, by extension, peoples' lives. The somewhat affected mannerism generally typical of the style, also manifested itself in Vrubel’s works of the Moscow period. His panels, ceramic dishes, stylized furniture, costumes, and vignettes, perfect as they are, are at the same time somewhat superficial.

Vrubel’s best Moscow works include the Fortune-Teller (1895), Lilac (1900), At Nightfall (1900), Pan (1899), The Swan Princess (1900) as well as the portraits of Savva Mamontov (1891), his business partner K. Artsybushev (95-96), and Painter’s Wife in Empire Dress (1898).

In 1896, in an opera in St. Petersburg, Vrubel heard the singer Nadezhda Zabela, and fell in love with her voice immediately. After the performance they got acquainted and, half a year later, married. At the time Vrubel, being less known, was often referred to as the husband of the famous opera singer Nadezhda Zabela. They settled in Moscow, and Nadezhda started to sing in Mamontov’s Private Opera.

In the last years of the 19th century, Vrubel was preoccupied with motifs of the Russian epic and fairy tales, largely due to the influence of Rimsky-Korsakov’s operas, e.g. The Snow Maiden, The Tale of Tzar Saltan, and others, where his wife sang the parts of the Snow Maiden, the Swan Princess, princess Volkhova, etc. He designed dresses for his wife, both for the stage and for real life, drew stage sets and designed costumes.

Later, he resumed work on the Demon theme. In 1901, he started his large canvas Demon Downcast. Exhibited in 1902, the painting overwhelmed the audience and won real fame for the artist. The painting, charged with motion, is strongly decorative. Striving to improve his masterpiece, Vrubel, who at the time, was becoming increasingly unbalanced, repainted the Demon’s face, his sinister eyes and his lips, twisted by pain numerous times. He insisted on repainting the picture even after it was on display, until he suffered the first of what would become a series of mental breakdowns.

Having recovered, Vrubel never again revisited the Demon theme. While in the hospital, he painted a great deal from life – portraits, landscapes, still lifes, as if in the hopes of rejuvenating the faded palette of his art through the painstaking study of the real world. Most of his late works were painted from life. They include numerous portraits of Vrubel’s wife, a portrait of his little son (1902), several self-portraits, and, at last, his remarkable Pearl Oyster (1904) where the mystifying play of the mother-of-pearl is rendered with the virtuoso brush of the artist.

Alongside these works, Vrubel produced many versions of The Prophet, inspired by the Pushkin’s famous poem of the same. In one of the versions, the Prophet’s face is actually a self-portrait while the figure of the six-winged Seraph is apparently Azrael, the angel of death. Azrael (1904), though not so famous as the Demon Downcast, is one of Vrubel’s greatest achievements. In his many variations on the Prophet theme, Vrubel relates a tragedy of the artist who, as he believed, failed to fulfill his mission to “sear the hearts of men with verbs”.

Unfortunately, many of Vrubel’s works have changed with time. The artist used many novel techniques, such as adding bronze powder to his oils to give them a glistening effect. The bronze darkened, and Vrubel’s paintings lost their initial coloring.

In 1906, when Vrubel was hospitalized in Dr. Usoltsev’s mental clinic, he continued to make studies for the Prophet and even his rapidly developing blindness did not prevent him from doing this. At the same time, Vrubel executed the Portrait of the Poet Valery Briusov, destined to be his last work.

During the last four years of his life, Vrubel's mental episodes became more frequent and greater in duration. Though the true cause of his illness is unknown, it is speculated that he suffered from porphyria.

Bibliography

Vrubel by N.Dmitriyeva. Russian Painters of the XIX century. Moscow. 1990.

Michail Vrubel: The Artist of the Eves by Mikhail Guerman. Parkstone Press, 1998.

The Art of Mikhail Vrubel (1856-1910) by Aline Isdebsky-Pritchard. UMI Research Press, 1982.

The Art and Architecture of Russia (Pelican History Art) by George Heard Hamilton. Yale Univ Pr, 1992.

A Dictionary of Russian and Soviet Artists 1420-1970 by John Milner. Antique Collectors' Club, 1993.

- Swan Princess.

1900. Oil on canvas. The Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow, Russia. Read Note.

- Pentecost. Detail.

1884. Fresco. Church of St. Cyril, Kiev, Ukraine. Read Note.

- The Virgin And Child.

1884-85. Zinc panel. Church of St. Cyril, Kiev, Ukraine.

- Pietà.

1887. A sketch for a mural in the Cathedral of St. Vladimir in Kiev. Watercolor, whitewash on paper. The Museum of Russian Art, Kiev, Ukraine. Read Note.

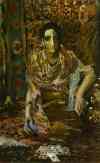

- Portrait Of A Girl Against A Persian Carpet.

1886. Oil on canvas. The Museum of Russian Art, Kiev, Ukraine.

- The Oriental Tale.

1886. Watercolor, whitewash on paper. The Museum of Russian Art, Kiev, Ukraine.

- Hamlet And Ophelia.

1883. Watercolor on paper. The Russian Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia. Read Note.

- The Seated Demon.

1890. Oil on canvas. The Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow, Russia. Read Note.

- Angel With Censer And Candle.

1887. Sketch for wall-painting of the cathedral of St. Vladimir in Kiev. Watercolor on paper. The Museum of Russian Art, Kiev, Ukraine.

- Fortune-Teller.

1895. Oil on canvas. The Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow, Russia.

- Lilac.

1900. Oil on canvas. The Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow, Russia.