David Alfaro Siqueiros Biography

David Alfaro Siqueiros (1896 - 1974) was a Mexican painter and one of the founders of the Mexican Mural Movement, one of the "Big Three", with Jose Clemente Orosco and Diego Rivera. He was also a Communist, life-long political activist, veteran of the Mexican Revolution and Spanish Civil War, sometime political prisoner, outspoken polemicist and would-be assassin. Throughout his life, he espoused the ideal that art, by its nature, had to be political in order to carry any substance, decrying the art of capitalist Europe and the United States. Siqueiros went, perhaps, the furthest of all the muralists in his attempts to combine his political views and aesthetic ideals with modern technical means to create a truly "public art"

Early Life

Jose David Alfaro Siqueiros was born on December 29, 1896, in the town of Santa Rosalia, in the northern Mexican province of Chihuahua (today, the town is called Camargo) as the second of three children. David's father was Cipriano Alfaro, an affluent lawyer who came from a line of well-to-do land-owners, a disciplinarian and a religious Catholic. David's artistic qualities came in large part from his mother's side of the family, Teresa Siqueiros de Barcenas, of Creole hacendado stock, which included musicians, poets and artists.

Teresa died in 1898, soon after giving birth to David's younger brother Chucho. Cipriano, unsure of how to deal with his three children, gave them into the care of their paternal grandparents Eusebita and Antonio Alfaro. Antonio, called "Siete Filos" or "Seven Blades" for his prowess, had fought on the Republican side against the Mexican Imperialists and the French in the War of the French Intervention (1861-1867). He was a strict disciplinarian, as befit his military background, but also held quite a different set of values than his cultured, university-educated son Cipriano. A true vaquero, he taught his grandchildren to ride half-tamed horses, handle fighting bulls that he raised at his ranch, and shoot. Eusebita, a much more gentle soul, took care to see that the children did not run completely wild, but she would unfortunately pass away a short time later. Siete Filos lost no time getting married again -- this would be his third wife -- after which the children were taken out of school and began a wholly carefree existence at the ranch.

When their father learned of this, he was not amused. In 1907, after a row with Siete Filos, Cipriano took his children back to live with him in Mexico City, where the boys were enrolled at the Catholic Franco-English School, run by the Marist monks. Here, for the first time, David was exposed to art: religious paintings by Mexican colonial artists, which produced an indelible effect on him. Later, he had his first art lessons at the Marist school with the painter Eduardo Solares Gutierez.

By 1910, the young Siqueiros had firmly decided to pursue a painting career, even if his father was not in love with the idea, and so, upon enrolling at the National Preparatory School in Mexico City, he simultaneously began taking art lessons at the San Carlos School of the National Academy of Fine Arts. These were years of great political upheaval in Mexico. Since 1884, the country had been ruled by Porfirio Diaz, nominally an elected president, but in reality retaining power through electoral fraud and violence. Needless to say, after more than a quarter-century of his rule, there was growing discontent in Mexico. In the countryside, peasants were forming into armed gangs to resist the hacienda system. By the outbreak of the Mexican Revolution in 1911, there would be entire guerrilla armies in the North and South, led by men like Pancho Villa, Emiliano Zapata and Pascual Orozco. Society in Mexico City was split down the middle, and Siqueiros was in a position to closely observe both ends of the spectrum. The students at the National Preparatory School, all hailing from affluent backgrounds, -- not to mention Siqueiros' own father -- had very conservative leanings, supporting the porifirista government or, at the most, advocating gradual reform. The art students at the San Carlos School were, by contrast, very left-leaning. The budding painter was not long in choosing sides.

Mexican Revolution

In 1911, the art students went on strike in protest against a particularly conservative professor. This rapidly escalated to a protest against the establishment in general, fanned by the outbreak of the Mexican Revolution. The artists' movement took inspiration from the ideas of Geraldo Murillo, called "Dr. Atl", who called for a rejection of European, especially French, academism -- then the prevalent school of art in Mexico -- and the creation of a Mexican National art, based on Pre-Columbian Native American art. The leaders of the students included many painters who would later become prominent figures in the Mural Movement, notably among them Jose Clemente Orozco.

Through his fellows, Siqueiros soon became familiar with communist and anarchist writings, embittering him further against the upper middle class to which he himself belonged. He had an argument with his father, witnessed by several of his father's wealthy friends, and, after an explosive scene, David left the house for good, lodging with his classmate Jose Maria Fernandez Urbina.

Meanwhile, the Mexican Revolution was heating up. In 1911, Porfirio Diaz had been ousted from power and Francisco Madero, a moderate pro-democracy politician, was elected president. Unfortunately, he was unwilling to take a hard-line stance against Diaz' supporters, which allowed many of them to retain important positions in the new government. In 1913, this allowed Victoriano Huerta, a general under the porfirista regime elevated to Commander-in-Chief of the Mexican army, to stage a successful coup against the new democracy. This plunged the country into a new period of chaos and violence that was to last for the next three years.

The art students were faced with a new political climate. The Huerta regime wanted to hear none of their grievances and was prepared to use violence to quell the unrest. The academy was raided. Several of the more outspoken student leaders were arrested and executed. The rest dispersed. Siqueiros, along with two friends, fled to Veracruz where they enlisted in the anti-Huerta Constitutionalist army, led by Venustiano Carranza.

While in the military, Siqueiros traversed much of Mexico. With his battalion, he fought in Veracruz, Chiapas and Oaxaca, before being sent west to Nayarit. He was soon promoted to 2nd Lieutenant and became a staff officer. After Huerta's fall from power, the victorious Constitutionalists fell out among themselves, with Pancho Villa and Emiliano Zapata aligning themselves against the new government of Carranzo. Fighting the villistas, Siqueiros would further see action through most of the north and west of the country. By the end of the war in 1918, some four years later, he had attained the rank of Captain and had been wounded. The military life had allowed him to interact with people from all walks of life that he would never otherwise have met -- workers, peasants, Indians. These experiences would influence his political views and give him a greater understanding

The First Murals

At the end of the war, Siqueiros settled in Guadalajara in the west of the country, where he began to paint after over 4 years in which he hadn't so much as held a brush in his hand. Works included portraits, executed primarily for profit, and paintings themed on the Revolution as the artist had experienced it. There is much religious imagery present in his output of this early period that would be absent after Siqueiros came fully to embrace Communist ideology.

Later that year, the artist married Graciela Amador (called "Gachita"), the sister of his comrade-in-arms Captain Octavio Amador. Soon afterwards, Siqueiros received a grant from the government to study art in Europe. On their way to the continent, the couple made a stop in New York City where Orozco was living in self-imposed exile, ultimately staying for the better part of a year. They finally arrived in Paris in 1919.

The French capital was a disappointment for Siqueiros in artistic terms. He quickly found Diego Rivera, with whom he had been acquainted before the outbreak of the Revolution, and who was then going through a Cubist period. Through him, David was introduced to Georges Braque and other Cubists. He admired and was influenced by the work of Cezanne. The artist found, however, the art of Europe of this period to be dispirited and decadent, narrowly concerned with painting as an end in itself, rather than its greater meaning for society and the world.

Siqueiros thought very differently of the murals of the Italian Renaissance, which he had the chance to see during a trip to Italy with Rivera. These, he claimed, were true public art, imbibed with meaning and accessible to the people. Later that year, while staying in Barcelona, the artist organized the publication of the magazine Vida Americana (American Life). In its first -- and only -- issue, he called for the creation of a national monumental art, based on pre-Columbian Native American art.

This idea had already captured the minds of the artistic avant-garde in Mexico and that very year, the Minister of Public Education Jose Vasconcelos inaugurated a government program to sponsor the painting of nationalistically-themed murals. When Siqueiros and Graciela finally returned to Mexico in 1922, work was already under way.

Siqueiros' first mural, painted in a stairway of the National Preparatory School, was The Elements (1922). The work is rather neutral in theme, but this was soon to change. In 1923, the artist joined the recently-formed Mexican Communist Party (PCM). Simultaneously, and at his urging, the artists formed the Union of Technical Workers, Painters and Sculptors, of which he was elected secretary general. In 1924, they began to publish the newspaper El Machete, with a stated goal of safeguarding the revolution and protecting the interests of the working class.

However, as the painters were leaning further to the left, Mexican politics were going into a reactionary phase. General Alfaro Obregon, hero of the revolution and president of Mexico since 1920, turned out to be no friend of democracy, and Siqueiros often criticized him on the pages of El Machete. Though the Union of Painters stood by Obregon in 1923 during an attempted counterrevolutionary coup, it was only because they saw him as the lesser of two evils.

In 1924, Siqueiros finished work on The Burial of the Martyred Worker, also in the National Preparatory School, taking the bold step of painting a hammer-and-sickle on the coffin. This provoked outrage on the part of the students at the School, then, as prior to the Revolution, representing the conservative element in society. There were several clashes, and the muralists took to carrying firearms to defend themselves. At one point, a battalion of Yaqui Indians, all devout supporters of the Revolution marched into the school to defend the murals.

A short while later, the artists received a major blow when Vasconcelos resigned from his post as Minister of Public Education. Quite soon, the government issued an ultimatum: either the painters had to abandon their Union (and El Machete, its publication), or they would be fired from the government payroll. The painters refused. When Diego Rivera adopted a more conciliatory tone, they voted to expel him from the Union. As a result, within a short period of time, he was the only muralist still allowed to work.

In response, Siqueiros turned to political activism. Leaving Mexico City, he traveled to the state of Jalisco, where he helped organize trade unions for the silver miners there. He was so successful that by 1927 he was head of the United Syndicate Confederation of Mexico (Confederacion Sindical Unitaria de Mexio, or CSUM), a national trade union organization that brought together miners, peasants, factory and railroad workers, schoolteachers and other professional groups. He quickly became persona non grata with the government, and was harassed and detained several times by the police. In 1928, he visited the Soviet Union to attend the Congress of Red Trade Unions. This only further enflamed the Mexican government against him.

During this time, he met Uruguayan writer and fellow Communist Blanca Luz Blum and became romantically involved with her, eventually divorcing his wife, Gachita. Blanca Luz did not meet with the approval of Mexican Communist Party, who questioned her loyalty and in 1930, Siqueiros was expelled from the party. By this point, however, the government was already hot on his heels.

In May of that year, he was arrested while participating in a May Day parade and thrown into prison, without trial or hearing of any sort. After several months that Siqueiros spent in agonizing limbo, unsure of his status and his future, he was allowed to go free, on condition that he would leave Mexico City and settle in the town of Taxco, without the right to travel.

Here, unable to continue his political activities, he at last returned to art -- with a fiery passion -- producing several hundred works in the span of just a few years. In 1932, he had his first one-man exhibition at the "Spanish Casino" in Mexico City, organized by his friends and sympathizers. The works included such politically-charged paintings as Mine Accident, Peasant Mother, Proletarian Mother and Portrait of a Dead Child.

Later that year, the Mexican authorities granted the painter permission to leave for the United States, in an effort to get rid of his noisome interference. In 1932, Siqueiros, accompanied by Blanca Luz and her son from an earlier marriage, arrived in Los Angeles.

Years Abroad

The Mexican Mural Movement had attracted the interest of American intellectuals. Siqueiros was invited to exhibit his works in Los Angeles and subsequently offered to teach fresco at the private Chouinard Art Institute. Here, he took the time to experiment with new exterior mural painting techniques, using modern materials and paintings. As usual, Siqueiros was unable to leave his outspoken politics behind. The practice mural he painted together with his class, depicting whites, blacks and Indians standing side-by-side, scandalized the American public. Within a decade, this one, together with one of the other two murals he'd painted during his stay were brought down.

In the United States, Siqueiros finally officially married Blanca Luz, though their relationship by this point was becoming increasingly strained. One of the final blows was the painter's meeting with the young and attractive Angelica Arenal, a fellow Mexican living abroad, and who would eventually become his third wife. Though there is no evidence of the two becoming romantically involved at this stage, Siqueiros and Blanca Luz would be divorced within a little over a year.

Howsoever, when the painter's visa expired several months later and the US government refused to extend it, he and Blanca Luz departed together for Montevideo in Luz's native Uruguay. There he read a series of lectures to the local artists about the social importance of art. In his painting Proletarian Victim (1933), he experimented, for the first time, with pyroxylin paint applied using a spray gun. This medium would later become his signature.

In June 1933, the painter was invited to lecture and paint in Argentina. Though Siqueiros was initially welcomed and even commissioned to paint a wall, the Argentinean intellectuals and government had not bargained for the sort of firebrand rhetoric that the artist brought with him. Very soon, Siqueiros fell foul of the increasingly fascist government, and was expelled from the country six months later, in December of 1933. Shortly before his departure, he broke up with Blanca Luz.

The painter sailed for New York. Despite his expulsion from the United States less than a year previously, he had no trouble getting back into the country. Soon, he was back in contact with American artists, and once more busy promoting his ideas, both artistic and political.

In 1934, in Mexico, a new president, Lazaro Cardenas, took office. Though originally anointed by the dictatorial jefe maximo Plutarco Elias Calles, he soon clashed with his patron and took control of the government firmly into his own hands, allowing exiled Mexican dissidents a safe return. Siqueiros returned in the beginning of 1935 and immediately resumed his political activity. He was soon reinstated in the PCM. The painter clashed bitterly with Diego Rivera, whom he saw as a traitor to the MMM. Their debates over each other's political stance, artistic vision and personal qualities for several months captivated the intellectual life of the country.

In January 1936, Siqueiros was sent as a delegate to the American Artists' Congress in NYC, where he exhibited two works painted using pyroxylin paint and a spray gun: The Birth of Fascism (1936) and Stop the War (1936). In New York, the painter was visited by Angelica Arenal -- the first time they had seen each other since his time in Los Angeles. Quite soon, and despite initial difficulties, the two had moved into an apartment together.

Spanish Civil War

In 1936, he was visited in New York by some Spanish friends who informed him of the revolutionary conflict brewing in their homeland. Without further ado, Siqueiros handed his studio over to his North American students, packed his bags and departed for Europe. He arrived in Valencia in January 1937, six months after the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War.

After giving one lecture on the revolutionary importance of art, the painter departed the relatively safe Republican-controlled regions and enlisted in the Fifth Regiment, a part of the International Brigades that fought in the Civil War. Commanded by the Italian communist and Comintern member Vittorio Vidali, who went by the nickname of "Carlos Contreras", it espoused a very hardline Stalinist ideology. Siqueiros saw action on his very first day at the lines, was restored to his Mexican Civil War rank of Captain, immediately promoted further to Major and became an aide to Enrique Lister, Vidali's second-in-command. With time, he was placed in command of the 82nd Brigade, consisting of Spanish anarchists, and by the Spring of 1937, he had been promoted to Lieutenant Colonel and was additionally in charge of the 46th Motorized Brigade, called "the Phantom Brigade" for its speed and efficiency. While Siqueiros was in Spain, his father died, back in Mexico.

In March 1937, Angelica arrived in Spain as a news reporter. Though Siqueiros instructed her to stay away from the front, she tracked down his unit and visited him there. A short time later, they were married in a military ceremony conducted by Enrique Lister. Their different duties -- his as military officer, hers as reporter -- would keep them apart for much of the war.

In November, Angelica received news that her mother had fallen ill. Siqueiros. meanwhile, was ordered to return to Mexico to acquire artillery and airplane optics for the Republican forces. The two traveled home together. While waiting on the equipment to arrive, the soldier-painter set about petitioning the Mexican government to expel Trotsky, to whom they had granted asylum. President Cardenas, though on very cordial terms with Siqueiros, turned a deaf ear to this request.

Returning to Spain in the beginning of 1938 with the optics, he was enlisted by the Spanish Military Intelligence Service (SIM) for a spying mission into Italy, where it was hoped his Mexican citizenship would help allay suspicion. He was successful, and soon back in Spain. For him and the other international brigadiers, however, the war was almost over. In September 1938, the Spanish Republicans signed an agreement with the Nationalists to expel the foreign troops in their ranks, though the Nationalists never kept their side of the bargain. Siqueiros, as the highest-ranking Mexican officer, was tasked with gathering up his countrymen and overseeing their withdrawal.

Back in Mexico, Siqueiros campaigned for the Cardenas government to allow Spanish refugees into the country, again bringing him into conflict with the authorities. After a long hiatus, he returned to painting, producing numerous easel works -- the Echo of the Scream (1937) and the Sob (1939) are two of the most notable, perhaps -- and, of course, murals. His major work from this period is the Portrait of the Bourgeoise (1939), painted for the Electricians' Union, again confirming his reputation as a master muralist.

Trotsky Assasination

In Spain, Siqueiros had worked closely with members of the Comintern (Коминтерн, Russian abbreviation of Communist International), the USSR-sponsored militant revolutionary organization, which advocated the use of any means deemed expedient, including terror tactics and assassination, for achieving its goal of overthrowing capitalist society and replacing it with Soviet-style communism; some of them were his direct superiors. Though never a formal member himself, the painter agreed with the organization's politics and, at least to some degree, its methods. When Trotsky, a sworn enemy of the Comintern's Soviet leadership, was given refuge in Mexico, Siqueiros, among other Mexican communists, vowed to remove him from the country -- one way or another.

After his numerous petitions to Cardenas failed to get Trotsky's visa revoked and only strengthened the Mexican government's resolve to guard their dangerous guest, Siqueiros decided the only solution was an assault on the heavily-guarded Trotsky residence. For this purpose, he brought together some 25 men, including artists working under him, associates from his unionizing days and old comrades-in-arms. Though he later claimed to be acting on his own agenda, it is almost beyond doubt that the Comintern played a hand in supplying him with money, supplies and manpower.

On the night of May 23-24th, 1940, Siqueiros and his men made their move. Overpowering the police guard posted around the exterior of the house, they gained access to the building via a traitor among Trotsky's bodyguards. Once inside, the would-be assassins opened indiscriminate fire with automatic firearms. In his bedroom, Trotsky and his wife Natalya hid behind their heavy bed as the house around them was riddled with bullets. Fortunately for them, the attackers were worried about the arrival of police reinforcements -- the commotion and gunfire could hardly be missed by anyone -- and did not bother to make sure their target was dead.

Suspicion fell on Siqueiros almost immediately. Several of his associates were arrested and pointed to him as the leader of the conspiracy. In the United States, where Siqueiros had previously been regarded as a nuisance rather than any sort of real danger, government agencies went wild, collecting any available information on the communist artist. The painter did not bother waiting for Mexico's law enforcement to take action and fled into the Jalisco countryside where he had contacts and sympathizers from his days of trade union activities. A veritable army of police officers and soldiers was raised for the manhunt. The painter was finally apprehended, with little incident, some four months later.

At the trial, Siqueiros maintained that his intention had never been to assassinate Trotsky, but merely to cause a provocation that would get him expelled from the country, and, in part due to his standing with the contemporary government of Mexico, in part to a more pro-Soviet shift of government ideology, he was cleared of the charge of attempted homicide and released on bail. With trials for trespassing, breaking-and-entering and property damage still pending, the new Mexican president Avila Camacho arranged to have Siqueiros expelled from the country. The painter was given a Chilean visa and airline tickets, and was boarding a plane shortly after his release, together with Angelica Arenal and her daughter Adriana.

Their airfare was paid until Panama, leading Siqueiros to suspect a plot to hand him over to the United States, which was firmly established in that country. Acting decisively, the artist cancelled his flight and instead bought tickets to Bogota, Colombia. There, before the startled authorities could take action, he rented a car and took the overland route for Ecuador. This was a move that no one had expected and Siqueiros effectively

| Tweet |

The Mexican family had no problem crossing the Ecuadoran border -- remote, mountainous, poorly guarded and little-travelled -- but beautiful. Though they had neither Colombian nor Ecuadoran visas, the border guards were bemused to find foreigners so far from the regular routes and let them pass. Via Ecuador and Peru, Siqueiros and Angelica eventually arrived in Chile, their original destination, where they caused another stir: the Chilean government had rescinded the painter's visa almost as soon as it had issued it, so the painter was now in the country illegally. Avila Camacho, however, was not overjoyed at the prospect of Siqueiros returning so soon, and high-level diplomacy to resolve the conflict followed. In the end, the painter was allowed to stay and even given a wall to paint, on condition that he would not leave the provincial town of Chillan.

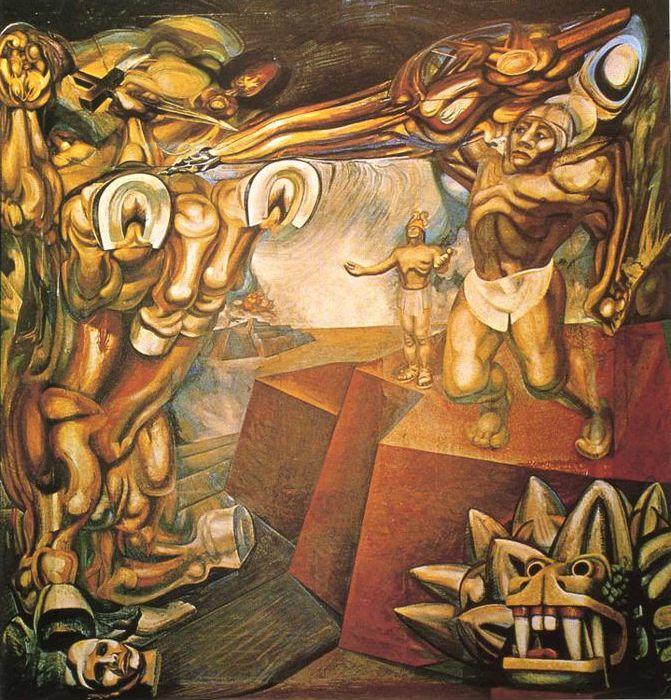

The area had been struck by earthquake earlier that year and a great rebuilding effort was underway. Siqueiros was asked to paint a mural on the interior of a new school hall. The result was Death to the Invader (1942), showing the struggle of Mexico's and Chile's indigenous peoples against European conquerors. The acclaim received by this mural, one of Siqueiros' masterpieces, finally convinced the Chilean government to allow him freedom of movement.

Meanwhile, the United States had finally become embroiled in the Second World War after the treacherous Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, and Siqueiros, due to his staunchly anti-fascist stance, became a temporary, though unlikely, ally. He was paid to go on a tour of South America preaching a message of anti-Fascism. However, all the painter's attempts to be allowed into the United States, where he had invitations for both exhibitions and mural commissions, were blocked by the State Department.

Instead, Siqueiros traveled to Cuba (then within the US sphere of influence), where, in order to fix his dire financial situation, he painted two murals for private parties: New Day of the Democracies (1943; now in the National Museum of Cuba) and Allegory of Equality and Fraternity of the White and Black Races in Cuba (1943). The latter work unfavorably shocked its owner, the wife of one of Cuba's wealthiest industrialists, and was taken down not long after its completion.

Return to Mexico

In 1943, Siqueiros managed to secure a guarantee from the Mexican authorities that he would not be prosecuted upon his return to the country since, though he had been aided in his flight by the president himself, he had jumped bail to do so. He returned to Mexico City in the end of that year.

Siqueiros and Angelica settled in a large house owned by his mother-in-law. For several months, Siqueiros kept a low profile, avoiding friends and newspaper reporters, and painting in quiet seclusion. However, as it became apparent that no retribution for his earlier flight was forthcoming, he made ready to re-enter the Mexican art scene with his usual flair. In the 40s, the Mexican Mural Movement had stagnated, for lack of funding and general interest; Siqueiros intended to re-vitalize it.

In the months that he had spent away from public view, he painted the mural Cuauhtemoc Against the Myth (1944) on the interior of his mother-in-law's house. This, he unveiled that summer. Though the initial reaction of many critics was that Siqueiros was behind the times and that Muralism was dead and buried, the painter was unfazed. With vitriolic attacks on "French formalism" -- the label that he gave all European continental art -- and enthusiastic editorials, Siqueiros whipped up support for the faltering Mural Movement. Soon, he had two new mural commissions: New Democracy (1944), to be painted in the Palace of Fine Arts in Mexico City, and Patricians and the Killers of Patricians (Patricios y Patricidas, only completed in 1968, amid endless obstructions, bureaucratic and otherwise), to be painted in Mexico City's old customs-house, the "ex Aduana". In 1947, the artist had a solo exhibition at the Palace of Fine Arts, his first in Mexico in some 15 years, where he showed El Coronelazo (1945, a self-portrait), Our Present Image (Nuestra Imagen Actual, 1947), Cain in the United States (1947) and the Devil in the Church (1947), among others.

During this time, the painter also resumed his political activities, re-joining the Mexican Communist Party, participating in rallies, writing articles and engaging in polemics. Soon, he was again arousing the ire of conservative elements in society -- not to mention the US intelligence agencies that had been keeping a close watch on him ever since the ill-fated attack on Trotsky. The brief camaraderie that the West had experienced with the Soviet Union during the Second World War was rapidly coming to an end, to be replaced by the Cold War. Siqueiros would feel the repercussions of this later. For now, however, he was in favor with the government.

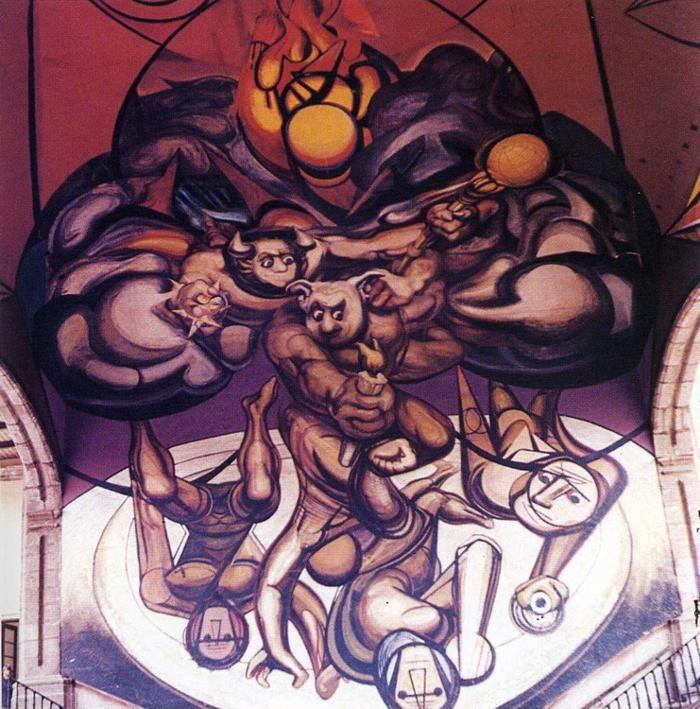

1950 marked an important breakthrough for the painter: at the Venice Bienniale, the first at which the work of the Mexican Muralists had been represented, he won second place, narrowly losing the first place to Henri Matisse. This was a profound, if pleasant shock for the artist, who had believed that Mexican art would never be recognized in "European Formalist" circles. That year, he received two new mural commissions in the Palace of Fine Arts, the products of which were Cuauhtemoc Reborn (1951) and The Torture of Cuauhtemoc (1951).

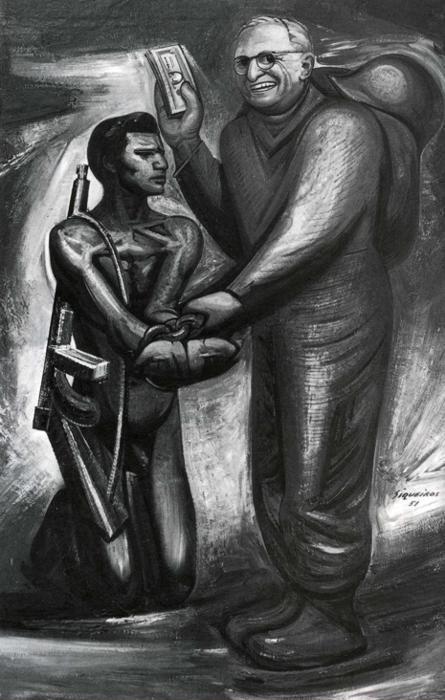

With the Cold War beginning to escalate, the new Communist cause celebre became an effort to stop the Korean War, which was termed a "manifestation of Western imperialism" that "went contrary to the wishes of the Korean people." Siqueiros, of course, was a spear-head of this movement in Mexico. In the Spring of 1951, he organized an exhibition entitled the Salon of May, after the substantially more famous Salon of Paris. Its political theme was a condemnation of war, and it was geared mainly towards lower-class people. Numerous artists were represented. Siqueiros unveiled one of his most famous and outspoken paintings: The Good Neighbor or How Truman Helps the Mexican People (1951).

In all, the 1950s became the painter's most productive decade, part of an overall surge in mural commissions throughout Mexico. In 1952, Siqueiros became involved in decorating the buildings of the new National Autonomous University of Mexico. He put forward the idea that muralists and architects collaborate on the project to create a "perfect synthesis" of art and design. Though his ideas were rejected out of hand, he was given several large walls to paint that would occupy him for a large portion of the next few years. Some of the products of this were: Man, the Master of the Machine, and Not the Slave (1952); From the People to the University -- From the University to the People (1956); New University Emblem (never finished).

Some others of his most notable works of the 1950s include the murals Velocity (1953) on the Chrysler Corporation building, For a Complete Social Security of All Mexicans (1955) in the Hospital de la Raza, and Defense of the Future Victory of Medical Science over Cancer (1958). He also painted an important series of easel works called the Streets of Mexico, which focused on the lower classes.

With increased interest in Mexican Art among Europeans, the painter made several tours abroad, reading lectures in France, Italy, the Netherlands, as well as Eastern bloc countries like Poland and Czechoslovakia. In 1952, he had an exhibition at the Paris Museum of Modern Art. This was marred by protests from, ironically, French Communists, who were angry over Siqueiros' participation in the attacks on Trotsky. In 1956, the painter visited China and India, where he was welcomed by top government figures: Zhou En Lai and Jawaharlal Nehru, respectively. Upon being shown the monumental art of the Hindus and Buddhists, the painter reportedly quipped: "Unless Socialist art can come up with something to equal this, I swear, I will have to become a Buddhist!"

1958 was a year of political turmoil in Mexico. Amid labor unrest, Adolfo Lopez Mateos became Mexico's new president through the government's method of imposing its candidates, and he took a hardline stance against trade unions. Bringing in the army, he dispersed protest marches and demonstrations and authorized mass arrests. Soon, several thousand protesters -- largely railroad workers -- were being held in prison without formal charges or trial.

Siqueiros naturally took a stance against the government -- and suffered for it. Funding for his murals was cut, both by the government and private parties, who wanted to distance themselves from his dangerous ideas. Used to suffering setbacks in his artistic career for the benefit of his political one, the painter paid no heed. In 1959, he founded the Committee for the Freedom of Political Prisoners and Defense of Democratic Liberties. The last straw, however, was when Siqueiros toured Venezuela and the newly-Communist Cuba with a series of political speeches, attracting international attention to the actions of the Lopez Mateos government.

The painter returned to Mexico to discover that a smear campaign had been unrolled against him in the government-controlled press. He received death threats. On March 31, 1960, he was arrested by the Special Security Police, though released a few hours later with a stern warning to stop his activism. Siqueiros refused to be intimidated. Then, on the day of August 9th, as the painter and Angelica were heading home for lunch, they realized they were being followed. Angelica, who was driving, sped away through the narrow streets of Mexico city and managed to lose their tail. They headed for the Cuban embassy, where Siqueiros hoped he would have the ambassador's protection. It was Sunday, however, and the embassy was closed to all business. Telling Angelica to go home, the painter took a cab to the house of his friend Dr. Carrillo Gil. It seemed, however, that this was being watched. Police agents arrived and knocked on the door. They presented no warrant and, overpowering both the homeowner and his guest, dragged Siqueiros off to the police station.

For the next several days, the painter was kept in solitary confinement and subject to several rounds of intimidating interrogation. Publicly, the police denied having him in custody. Siqueiros' fame and high profile, however, meant that this could not be kept up for long and, a week later, the artist was moved to a regular prison with the other political prisoners. The government had little to formally charge Siqueiros with -- incarceration served to stop the painter's political activities, and now the prosecution dragged its feet as much as possible. The trial took place some 17 months after the artist's arrest; he was accused of sedition. The guilty verdict and an 8-year sentence were delivered 2 months later.

An international campaign calling for the liberation of Siqueiros unrolled almost immediately. In France, a group of painters led by Picasso petitioned for his release. There was much outcry among the artists of the United States, and even John and Jackie Kennedy took an interest, though the State Department advised that it would be unwise for the USA to interfere in Mexico's internal affairs. The Mateos Lopez administration was flooded with letters demanding the artist's immediate release and, in the end, they succeeded. On July 13, 1964, nearly 4 years since his arrest, Siqueiros was led out of his cell.

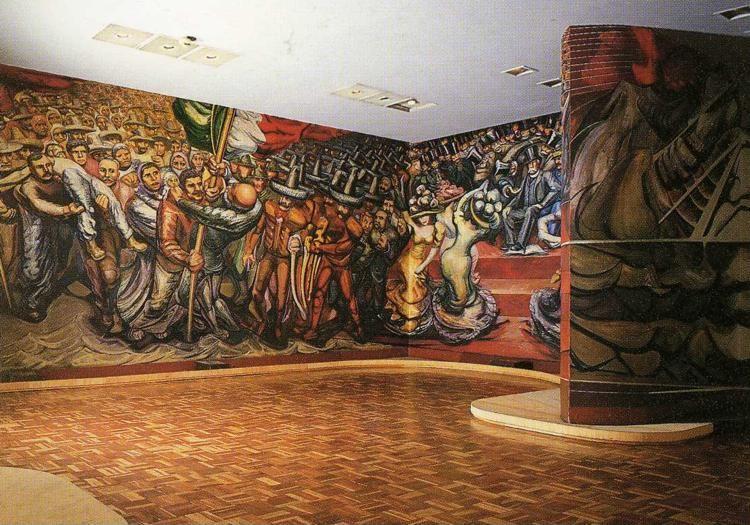

The artist had aged visibly during his imprisonment. He had been allowed to paint in prison -- in fact, he had amassed a small fortune through the sale of these "Prison Paintings" -- and the toxic pyroxylin paints that he used had taken a toll on his health. Inwardly, he was unchanged. Not long after his release, he was busy at work on the mural projects he had been forced to abandon because of his time in jail. From Porfirio to the Revolution (1966) is by far one of Siqueiros' most iconic works: eloquent, powerful, straightforward and executed with great technical mastery. His political sympathies were equally unchanged, and he continued to attend protests, speak at meetings, file petitions and equivocate endlessly against the injustice of the Mexican political system and society.

In 1967, Siqueiros was presented with the Lenin Peace Prize -- the Soviet equivalent of the Nobel Peace Prize.

Though the painter continued to be productive through the end of the 60s and early 70s, he was already very ill with prostate cancer. A strong and stubborn man, however, Siqueiros refused to see the doctors, until the pain became too severe to endure. He was diagnosed in May 1973, by which point little could be done to help him. The verdict was given to him beneath his own mural, Defense of the Future Victory of Medical Science over Cancer (1958), painted more than a decade earlier.

Siqueiros died on Sunday, January 6, 1974, putting a cap on a long and adventurous life. He was interred in the Rotunda of Famous Men of the Civil Pantheon of Mourning, in Mexico City. Hundreds attended the funeral, including people from all walks of life: fellow artists, politicians, Party comrades and simply admirers of his art.

Bibliography

Me Llamaban El Coronelazo (Меня называли лихим полковником) by David Alfaro Siqueiros. Moscow, 1980.

Mexican Muralists: Orozco, Rivera, Siqueiros by Desmond Rochfort. Chronicle Books, 1998.

Siqueiros: His Life and Works by Philip Stein. International Publishers, 1994.

- The Elements.

1922. Ceiling over stairway.Encaustic. National Preparatory School, Mexico, Mexico.

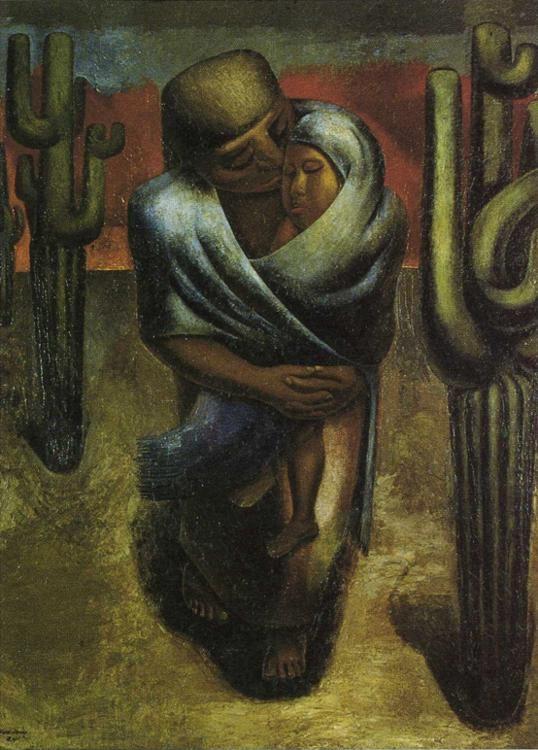

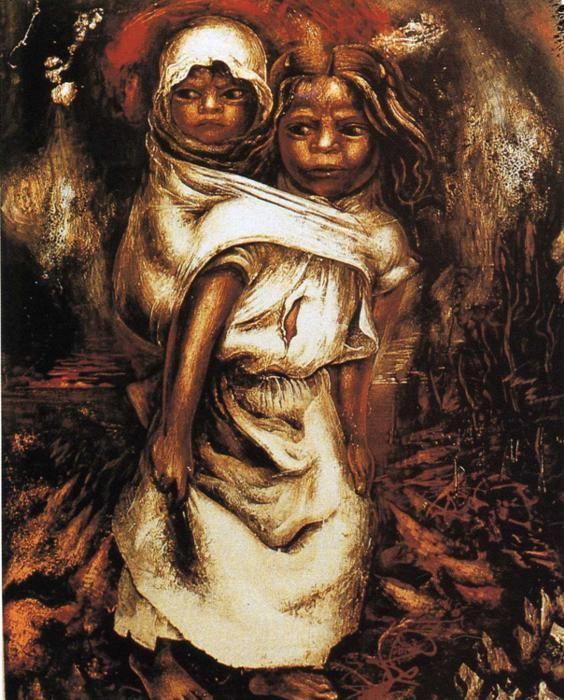

- Peasant Mother.

1929. Oil on burlap. 249 x 180 cm. Museum of Modern Art, Mexico, Mexico.

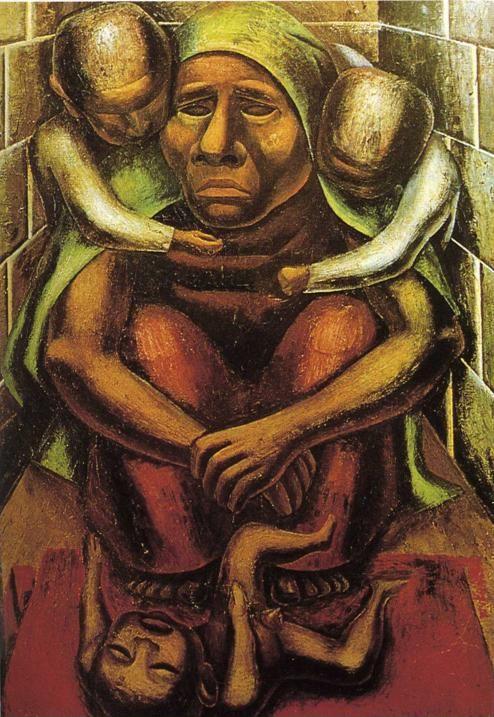

- Proletarian Mother.

1929. Oil on burlap. 249 x 180 cm. Museum of Modern Art, Mexico, Mexico.

- Portrait Of A Dead Child.

1931. Oil on burlap. 96 x 74 cm. Private collection.

- Birth Of Fascism.

1936. Pyroxylin on Masonite. 75 x 60 cm. Sala de Arte Publico Siqueiros, Mexico, Mexico.

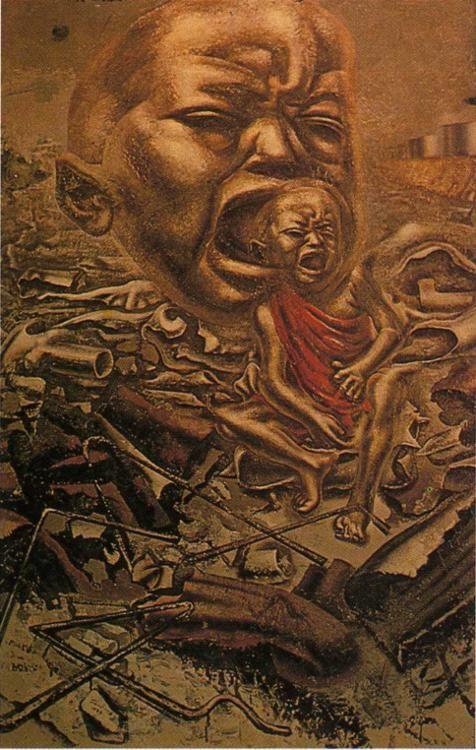

- The Echo Of The Scream.

1937. Pyroxylin. 125 x 90 cm. The Museum of Modern Arts, New York, NY, USA.

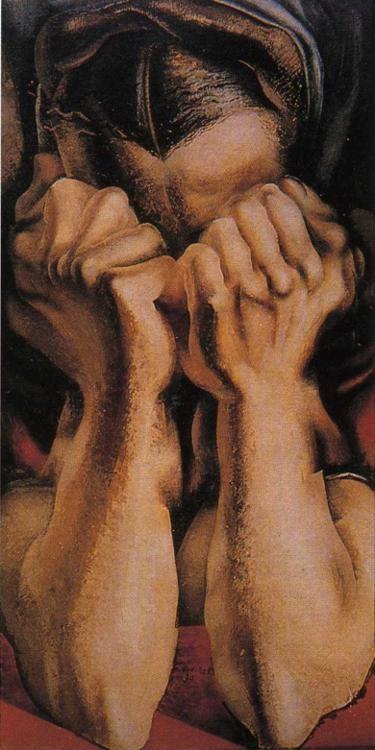

- The Sob.

1939. Pyroxylin. 122 x 61 cm. The Museum of Modern Arts, New York, NY, USA.

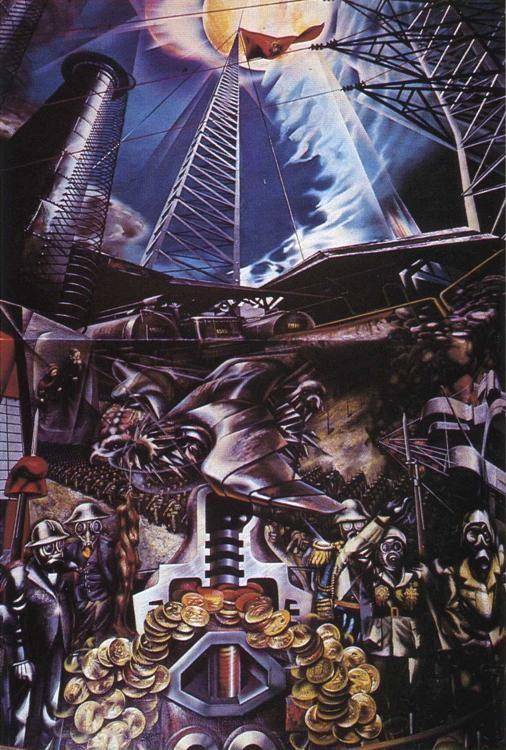

- Portrait Of The Bourgeoisie.

1939. Pyroxyline. Electrician's Union. Mexico, Mexico.

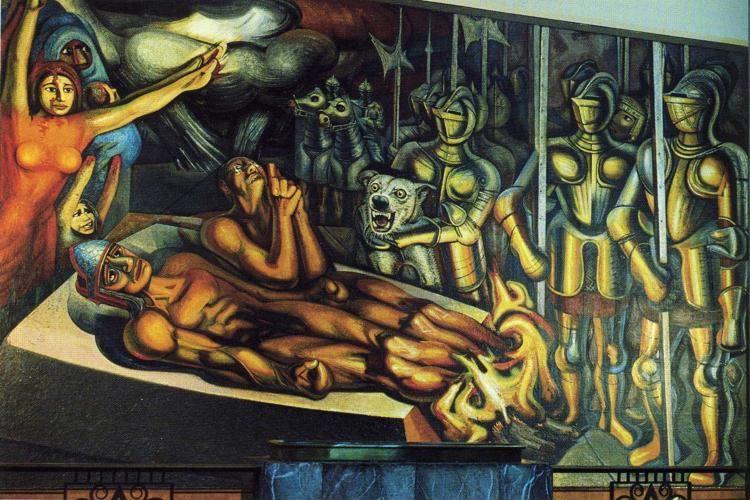

- Death To The Invader.

1941-42. Pyroxylin, mural. 240 sq. m. Escuela Mexico, Chillan, Chile.

- Cuauhtemoc Against The Myth.

1944. Pyroxylin. 75 sq. m Tecpan de Tlatelolco, Mexico, Mexico. Read Note.

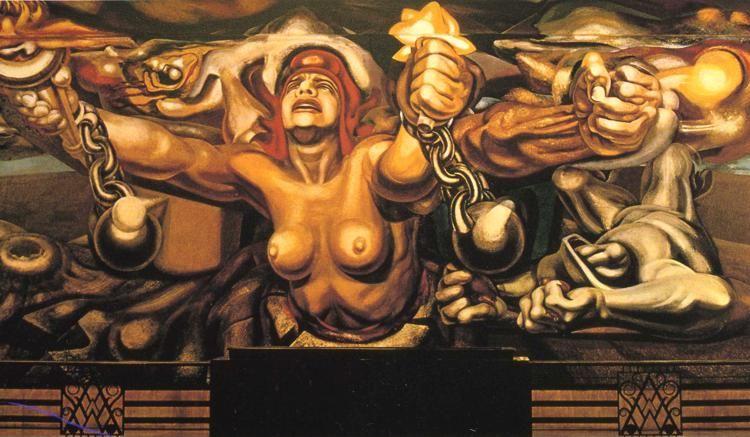

- The New Democracy.

1944-45. Pyroxylin on canvas. Palace of Fine Arts, Mexico City, Mexico.

- Patricians And The Killers Of Patricians.

1945. Pyroxylin and acrylic celotex on masonite. The work remained uncompleted. Ex Aduana de Santo Domingo, west wall, Mexico City, Mexico.

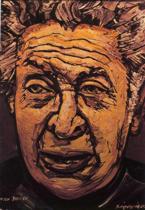

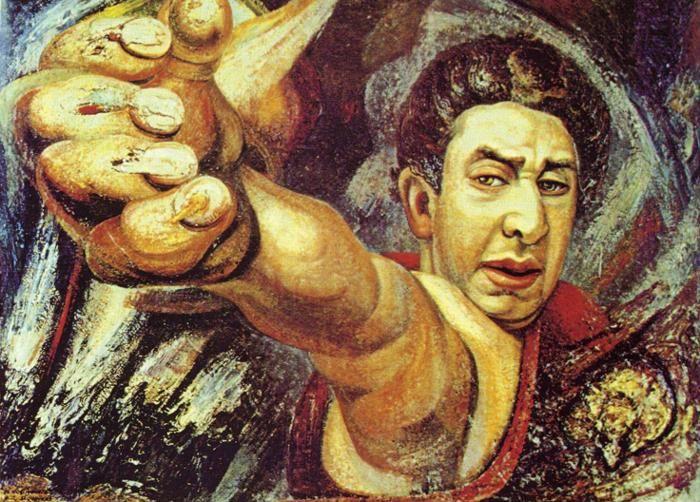

- El Coronelazo, Self-Portrait.

1945. Pyroxylin. Museum of Modern Art, Mexico, Mexico.

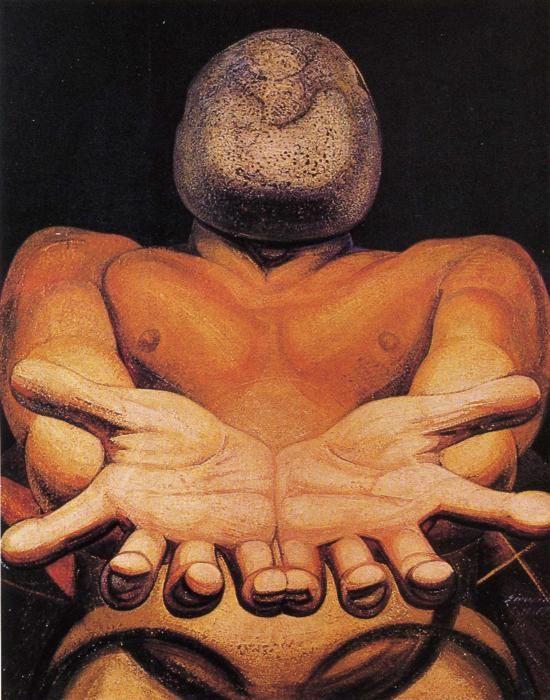

- Our Present Image.

1947. Pyroxylin. 18 x 5.5 cm. Museum of Modern Art, Mexico, Mexico.

- Cain In The United States.

1947. Pyroxylin. 93 x 76 cm. Carrillo Gil Museum, Mexico, Mexico.

- The Devil In The Church.

1947. Pyroxylin. 218 x 156 cm. Instituto Nacional de Bellas Artes, Mexico, Mexico.

- The Resurrection Of Cuauhtemoc.

1950. Pyroxylin on masonite. Palace of Fine Arts, Mexico City, Mexico. Read Note.

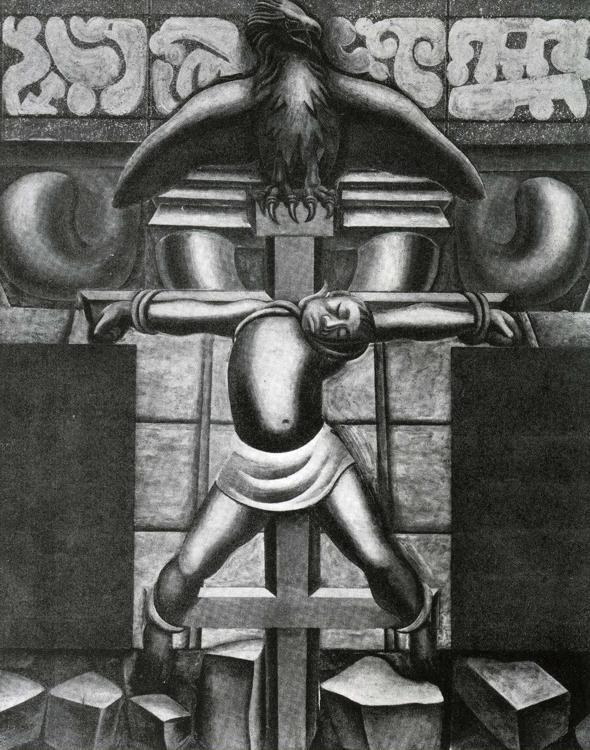

- The Torment Of Cuauhtemoc.

1950. Pyroxylin on masonite. Palace of Fine Arts, Mexico City, Mexico. Read Note.

- The Good Neighbor.

1951. Pyroxylin. 250 x 150 cm. Instituto Nacional de Bellas Artes, Mexico, Mexico.

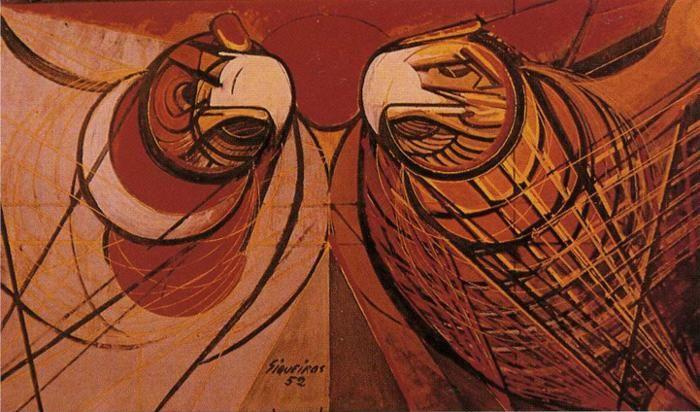

- Man The Master, Not The Slave Of Technology.

1952. Detail. 1952. Pyroxylin on aluminum. National Polytechnic Institute, Mexico City, Mexico.

- The People For The University. The University For The People.

1952-56. Relief Mosaic. National Autonomous University of Mexico, Mexico City, Mexico.

- New University Emblem.

1952. Pyroxylin painted sketch. 125 x 70 cm. Private collection.

- For The Complete Safety Of All Mexicans On Work.

1952-54. Vinylite and pyroxyline on plywood and fiberglass. Hospital de la Raza, Mexico City, Mexico.

- Defense Of The Future Victory Of Medical Science Over Cancer.

1958. Detail. Acrylic on plywood. National Medical Center, Mexico City, Mexico. This mural was taken down after irreparable damage to the building in the Mexican earthquake of 1985.

- From The Dictatorship Of Porfirio Diaz To The Revolution.

1957-65. Acrylic on plywood. Right-hand section showing the Cananean miners' strike of 1906, with William C. Green of the Green Consolidated Mining Company of America, and Fernando Palomares, leader of the Mexican Liberal Party, struggling for the possession of the flag of Mexico. On the right-hand wall Porfirio Diaz, Ministers and Courtesans. Hall of the Revolution, National History Museum, Chapultepec Castle, Mexico City, Mexico.

- El Senor Dell Veneno.

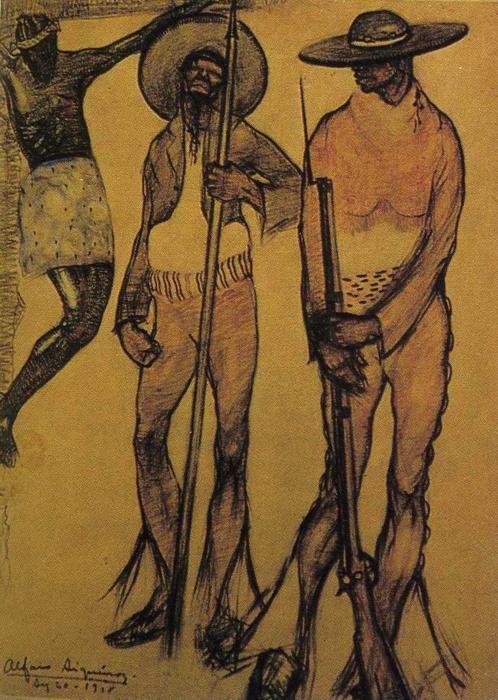

1918. Watercolor and crayon. 58 x 46 cm. Private collection.

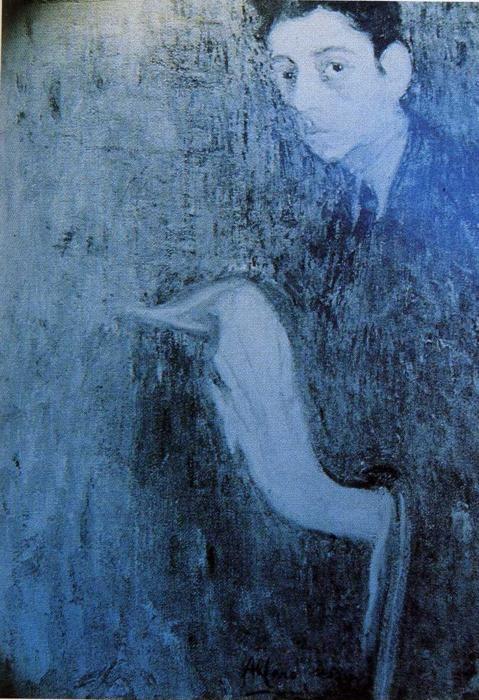

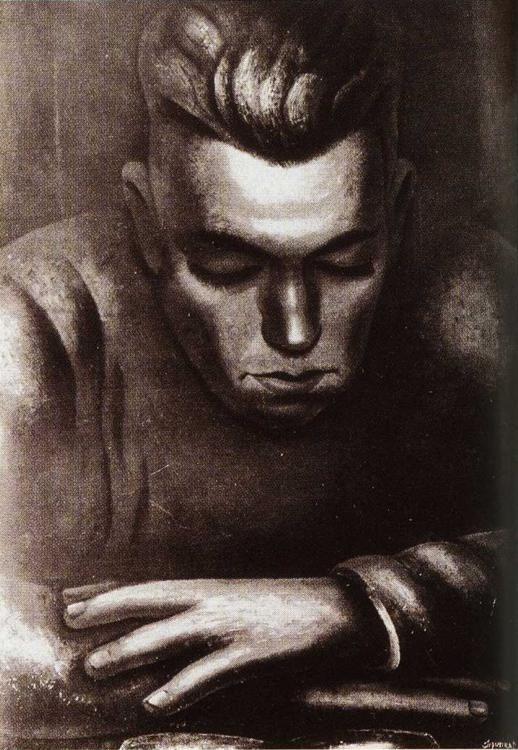

- Carlos Orozco Romero.

1918. Oil on burlap. 86 x 58 cm. Private collection.

- The Dance Of The Rain.

1919. Watercolor. An Art Nouveau illustration published in the newspaper "", January 24, 1919.

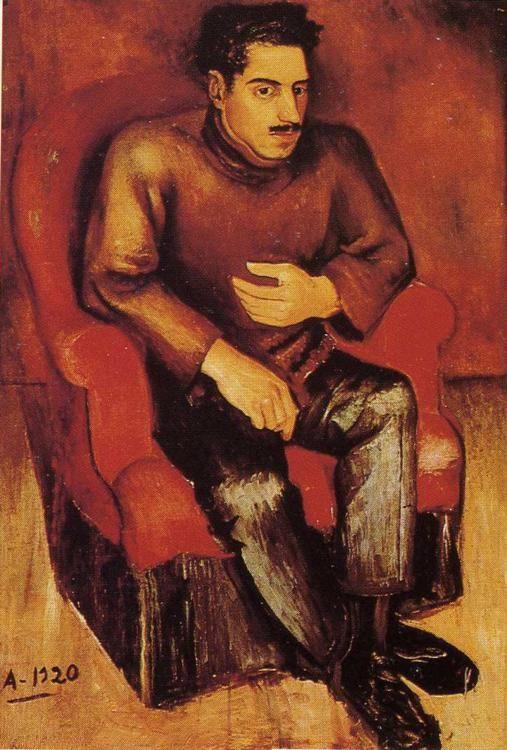

- Amado De La Cueva.

1920. Oil on canvas. 127 x 91 cm. Patrimony of Jalisco, Guadalahara, Mexico.

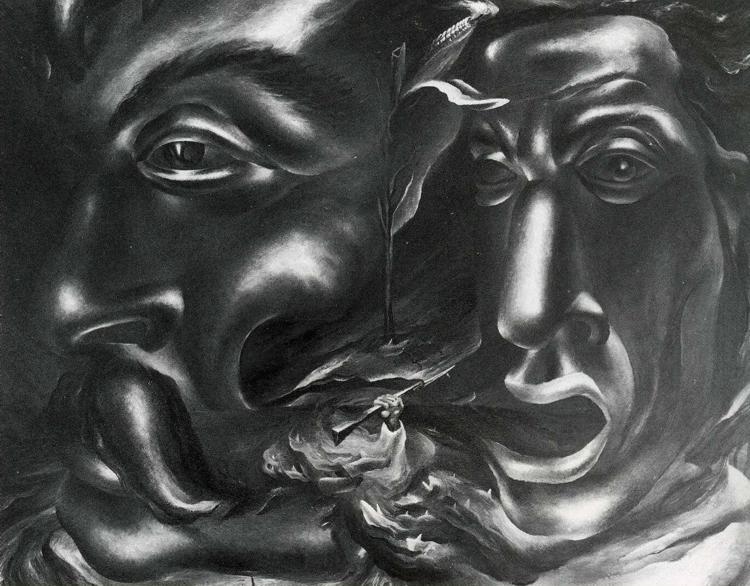

- Zapata And Lombardo Toledano.

1930. Oil on burlap. Mexican Revolution threatened as seen in the distorted faces of Zapata and Toledano. The arm of the Revolution sinks in the shark-infested waters.

- Hart Crane.

1931. Oil on canvas. 79 x 63 cm.

- Guerilla Fighters. Sketch For The Mural Tropical America.

1932. Pencil and india ink. 28 x 21 cm. Private collection.

- Tropical America.

1932. Reconstructed rendering. Cement fresco mural (obliterated with white wash). Olivera Street, Los Angeles, CA, USA.

- Tropical America. Detail.

1932. Detail. Cement fresco mural (obliterated with white wash). Olivera Street, Los Angeles, CA, USA.

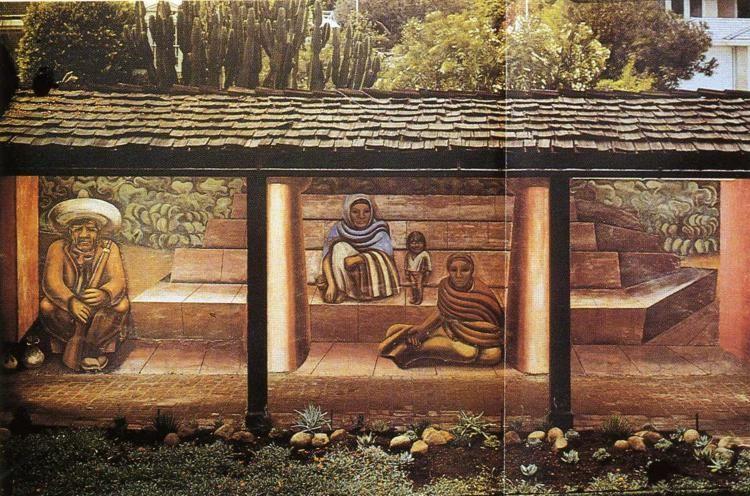

- Portrait Of Present Day Mexico.

1932. Mural in fresco. Private collection.

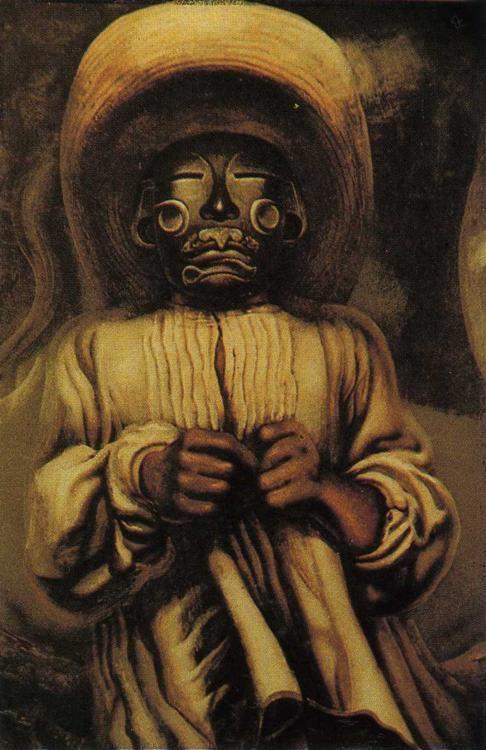

- The Child Mother.

1936. Pyroxylin. 76 x 61 cm. The Santa Barbara Museum of Art, Santa Barbara, CA, USA.

- Head Of A Woman.

1936. Pyroxylin on Masonite. 77 x 61 cm. Private collection.

- George Gershwin.

1936. Oil on canvas. 254 x 161 cm. Private collection.

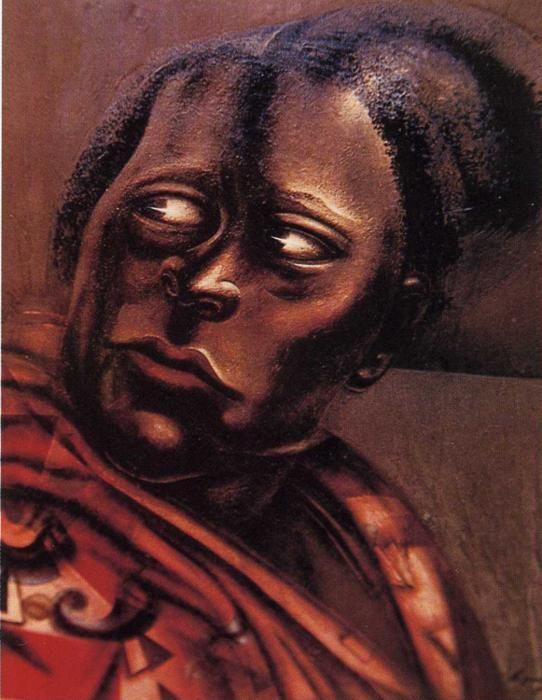

- Ethnography.

1939. Pyroxylin. 171 x 81 cm. The Museum of Modern Arts, New York, NY, USA.

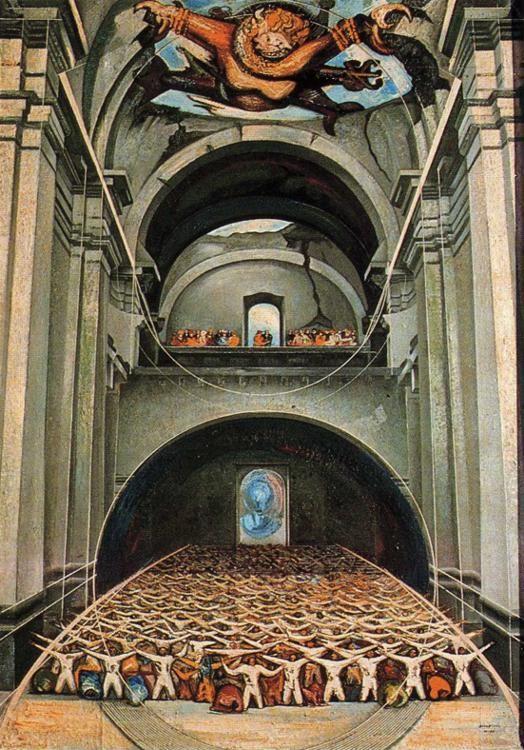

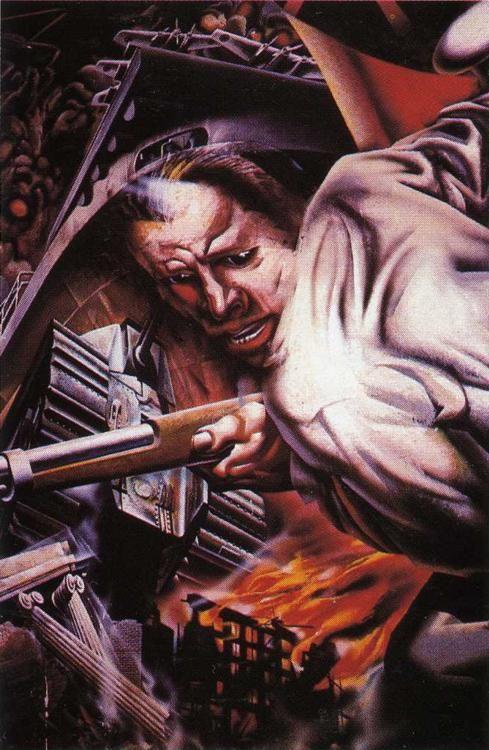

- Portrait Of The Bourgeoisie. Detail.

1939. Pyroxylin. Electrician's Union. Mexico, Mexico.

- Portrait Of The Bourgeoisie. Detail.

1939. Detail. 1939. Pyroxylin. Electrician's Union. Mexico, Mexico.

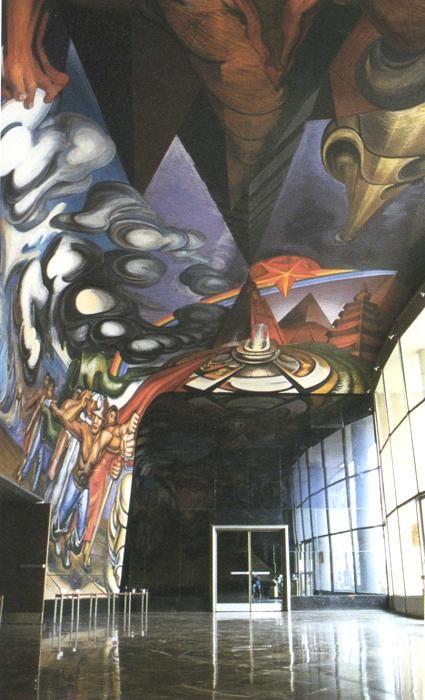

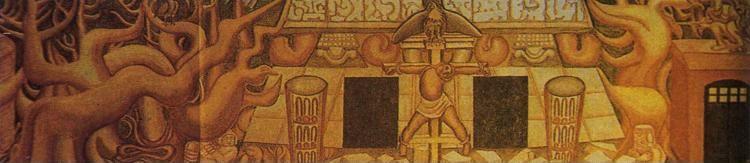

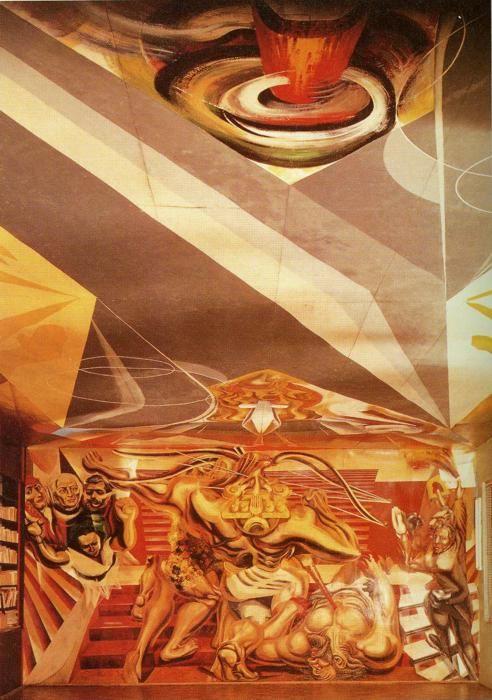

- Death To The Invader.

1941-42. Pyroxaline on masonite and plywood. Escuela Mexico, view of the south wall, Chillan, Chile.