Zinaida Serebriakova Biography

Zinaida Evgenievna Serebriakova, nee Lanceray, (10 December 1884 - 19 September 1967) holds a unique place in the history of Western art. A realist painter at a time when art was experimenting rapidly and the dominant movements in the art world were Futurism, Expressionism, Cubism, Fauvism and the Art Nouveau, her unique touch brought her recognition and the respect of her peers, even as the traditions she represented were becoming less fashionable and irrelevant to the contemporary world. With some of her most acclaimed work being portraits, she can be described as the Last Great Portrait Painter.

The artist was born Zinaida Evgenievna Lanceray into a dynasty of professionally creative people. Her father was Evgeny Lanceray, a sculptor, her maternal grandfather was Nikolai Benois, a prominent architect, and her great great grandfather was Catarino Cavos, the composer. All three branches of the family: the Lanceray, the Cavos and the Benois were foreigners who had settled in Russia in the end of the 18th Century, when Russia, on the one hand, was going through a phase of increased interest in Western European culture, while Western Europe was going through a period of upheaval, with the French Revolution and the Napoleonic Wars. The Benois were French, while both the Lancerays and Cavos were Italian.

Zinaida’s father Evgeny died young, when she was only 2 years old. As a result, her mother, Ekaterina Nikolaevna, moved along with her 6 children into the house of her father (Zinaida’s grandfather), Nikolai Benois.

The Benois household was a great environment for an artistically-inclined young girl. Benois was friendly with many figures of St. Petersburg’s art, theater and musical world, and practically everyone in the family dabbled in one or more of these either professionally or as a hobby. Zinaida learned to both make music and appreciate the stage, but it was art--sketching and watercolors--that fascinated her from an early age. The Benois family, unusually for the time, also believed in the importance of girls having a well-rounded education, and Zinaida attended the selective Kolomensky Women’s Gymnasium, which she graduated in 1900.

The family also owned an estate in the Ukrainian village of Neskuchnoye (literally “Not Boring”), located in modern-day Kharkiv Oblast. Zinaida spent many summers here, both as a child and as a young woman, and the intimate, family atmosphere of the country life was a key influence on the development of her personal style. Many of the major works of her early period were painted at Neskuchnoye.

After completing her education at the gymnasium, Zinaida expressed her desire to pursue art more seriously, a decision that was met supportively by her mother and grandfather. In 1901, she attended the art school of Princess Tenisheva, but was only able to do so for 25 days, before the school closed down. Her formal training continued in the studio of artist Osip Braz, who was an old-school neo-Classicist, and had his students practice by copying the works of the old masters at the Hermitage.

In 1905, she travelled to Paris to see what French art studios had to offer her. However, at this time, the various branches of modern art were all the rage in Paris, and Zinaida was frankly unimpressed with them. She enrolled at the Academie de la Grande Chaumiere where she studied sketching and watercolors.

That same year, Zinaida married her cousin Boris Anatolievich Serebriakov, an engineering student, and became Zinaida Serebriakova, the name she is best known by to the world. Over the next few years, the couple would have 4 children: Evgeny, Alexander, Tatyana and Ekaterina.

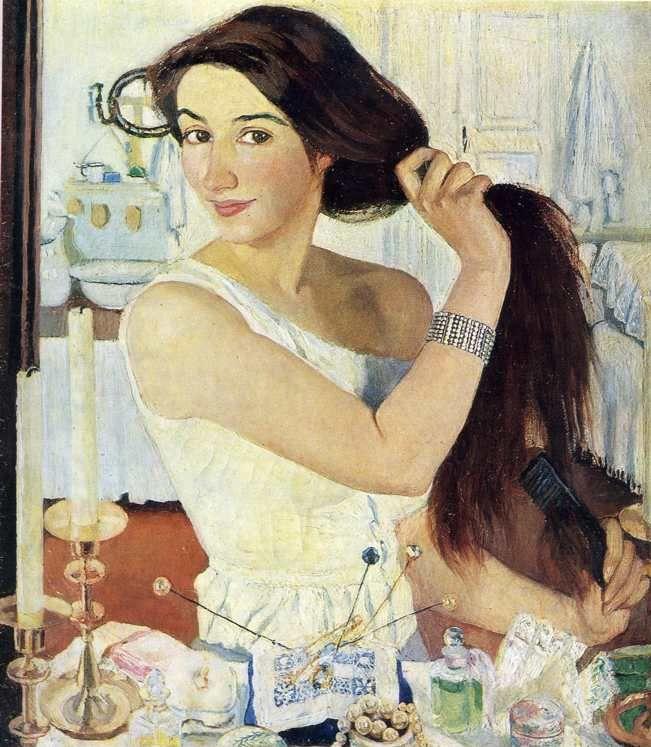

1910 saw a major professional milestone for Serebriakova: she participated in her first exhibition “The Contemporary Portrait of the Russian Woman” with her painting At the Dressing Table (1909), sometimes also called Au Toilette. In this self-portrait, the artist, wearing only a dressing gown, is standing at her dressing room table and brushing her hair. We see her as she would see herself in the mirror. This compositional simplicity, however, belies the strength of the painting. It was simultaneously titillating--the intimate setting, the dressing gown, the bare shoulder, the loose hair, the coy smile--and demure, lacking the unnatural deliberacy that is often typical of self-portraits. As a result, the painting was a sensation among St. Petersburg art critics, and is still one of Serebriakova’s best-known works.

Later that year, she was invited to participate in an exhibition of the Union of Russian Artists, and starting in 1911, became, together with her brother Evgeny Lanceray, a regular exhibitor with the re-established Mir Iskusstva society.

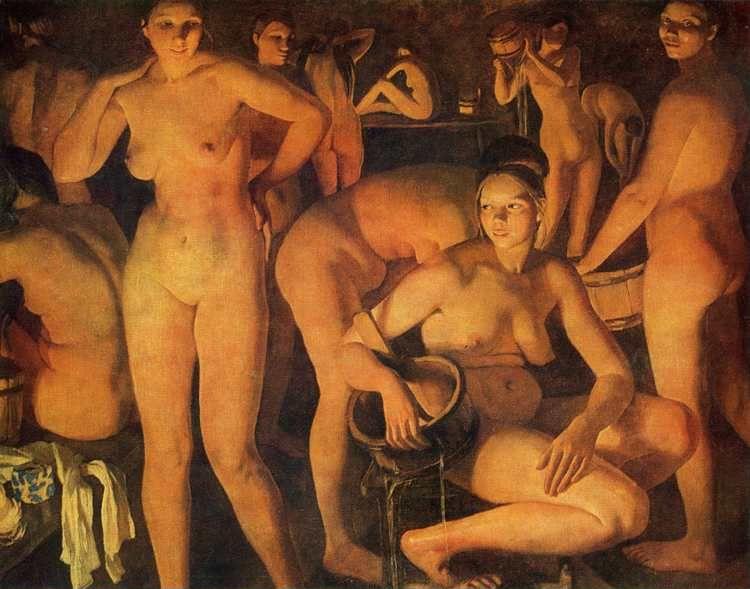

Serebriakova’s output of the time included many portraits, particularly of members of her own family and friends. During her stays in Neskuchnoye, she would paint landscapes and scenes of peasant life. The female form, both nude and clothed, becomes a particular staple of the period 1910 to 1917, with such notable works as The Bather (1911), The Bath House (1913), Harvest (1915) and Bleaching Linen (1917). For the more complex compositions, such as the latter two paintings, Serebriakova would often have one peasant girl pose for all of the figures on the canvas.

The period roughly between 1900 and 1917 would often be described by the painter as “my happy years”.

Serebriakova was in Neskuchnoye with her children when the Russian Revolution began in 1917. Fearing a return to St. Petersburg, which was the epicenter of the turmoil, they rented an apartment in the nearby city of Kharkiv. In 1919, Serebriakova’s husband, Boris, was arrested in Moscow by the Bolsheviks for unclear reasons. In jail, he contracted typhus and died only a short while later. This was the beginning of an especially difficult period in Serebriakova’s life.

For the next few years, the family resided in Kharkiv. Constrained financially, Serebriakova found work making sketches of dig sites for the Archaeology faculty of Kharkiv University. She also continued to paint, finding inspiration in the everyday life around her, primarily her children. Perhaps the most notable work of this period is the House of Cards (1919).

By 1920, circumstances made possible a return to St. Petersburg (by then, it had been renamed Petrograd). Back in 1917, Serebriakova had been nominated to become a member of the Russian Academy of Art, one of the first and one of very few women to be so recognized. However, there had been no time for the Academy to vote on her nomination due to the outbreak of the revolution. Now, the Academy was inviting her to teach some of its courses.

She and her children moved back into the house where she’d grown up: the house of her grandfather Nikolai Benois, which at this point in time housed not only him and his household, but also numerous other members of the Lanceray and Benois families and friends, who had been similarly forced into dire straits.

In 1922, the writer Sergei Ernst, a longtime friend, published a biopic of her life. Despite this and the success at exhibitions of her series of paintings of ballerinas from the Mariinsky Theatre, it was difficult to get by in a Russia, now the USSR, impoverished by war and revolution. In 1924, Serebriakova left for Paris, temporarily, she thought, to see if she could make some money abroad. During the brief time she was gone, however, there was a crackdown on travel to and from the USSR, and the painter was barred from returning. Eventually, the Soviet authorities allowed two of her four children to travel to France to join her: Alexander and Catherine. Tatiana and Evgeny were not allowed to leave.

Life as an expatriate was not easy, but Serebriakova managed to earn commissions as a portrait painter. She still felt disdain for modern art. Much of her money was sent back to her family in the USSR, so her life couldn’t exactly be described as comfortable. In pursuit of work, she travelled widely and often, including visits to England, Belgium, Germany, Italy, Switzerland and all over France. Her output consisted of the portraits that were her main source of income, landscapes and genre paintings.

In her own opinion, the works she painted abroad were inferior to her earlier paintings, and blamed it on a lack of time and opportunity. To do the type of painting that she did best, she needed to live and spend time in the countryside. Financial necessity forced her to live in cities.

Despite this, she did attract positive attention from critics. In 1927, she had a solo exhibition at the Charpentier gallery in Paris, followed by a 1928 solo exhibition in Leningrad, as St. Petersburg had recently been renamed. Soon afterwards, the political climate in the USSR changed rapidly for the worse, and this would be the painter’s last exhibition in her homeland for over 30 years.

A major project of Serebriakova’s that, unfortunately did not survive to our day except as copies was the decorative work on the country home of Belgian aristocrat and industrialist Baron Jean de Brouwer. For it, Serebriakova with the help of her son Alexander, also an aspiring artist, painted a series of decorative panels: four panels with laying nudes representing the four seasons, and four panels with upright nudes, representing Justice, Nature, Art and Light. Unfortunately, the de Brouwer mansion was looted and burned during the Second World War.

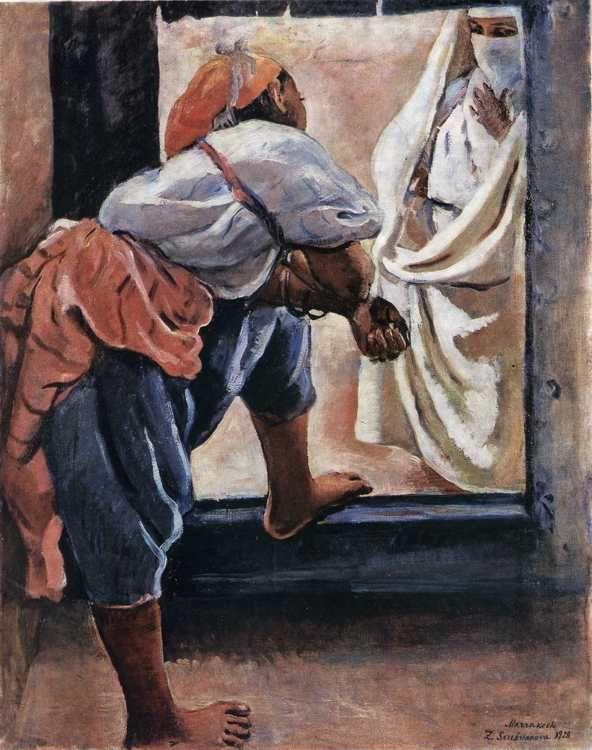

De Brouwer’s patronage also enabled Serebriakova to travel to Morocco, a country which left a bright and indelible mark on her art, with such paintings as Moroccan Woman in White (1928) and Marrakesh: Female Figure Standing in the Doorway (1928). She would return to the country several times.

In 1947, Serebriakova finally gave up her Soviet citizenship and became a citizen of France. She had retained hope of one day being able to return to her country of birth, but with the world rapidly heading towards a Cold War and no sign of change in the Soviet regime, this hope seemed ever more dim. This would change, however slightly during the Khruschev Thaw, when some of Stalin’s repressive policies were reversed. For her early paintings of peasants in the countryside, Serebriakova was recognized as having solidarity with the working masses, and her art stopped being taboo in the USSR. More importantly for the painter, her relatives were finally allowed to visit her in Paris. It would be awhile longer, however, before the rehabilitation turned into widespread recognition.

1965 saw a major retrospective exhibition of Serebriakova’s work in Leningrad. It featured both old works that the painter had left behind when she left Russia, and new work that she had painted abroad. Serebriakova, by then 81, was invited to visit. This became the first time she set foot in her native land in 41 years.

Serebriakova died in Paris on September 19, 1967.

Bibliography

Remarkable Russian Women in Pictures, Prose and Poetry by Marcelline Hutton. Zea Books, 2014.

Women-Artists of the Russian Avant Garde 1910-1930/ Kunstlerinnen de russichen Avantgarde. Galerie Gmurzynksa, 1980.

- Woman At The Mirror. Self-Portrait.

1908-9. Oil on canvas mounted on cardboard. 75 x 65 cm. The Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow, Russia.

- The Bather.

1911. Oil on canvas. 98 x 89 cm. The Russian Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia.

- Bath House.

1913. Oil on canvas. 135 x 174 cm. The Russian Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia.

- Harvest Time.

1915. Oil on canvas. 142x177cm. The Art Museum, Odessa, Ukraine.

- Bleaching Linen.

1917. Oil on canvas. 141.8 x 173.6 cm. The Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow, Russia.

- The House Of Cards.

1919. Oil on canvas. 65 x 75.5 cm. The Russian Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia.

- A Moroccan Woman In White.

1928. Oil on canvas. 93 x 74 cm. The Russian Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia.

- Marrakesh. Female Figure Standing In The Doorway.

1928. Oil on canvas. 92 x 73 cm. Donetsk Regional Art Museum, Donetsk, Ukraine.

- A Peasant Girl.

1905. Tempera and watercolor on paper. 62.5 x 34.9 cm. Private collection.

- A Peasant Girl. Detail.

1905. Tempera and watercolor on paper. 62.5 x 34.9 cm. Private collection.

- Portrait Of A Nurse.

1907. Oil on canvas. 74 x 56 cm. Taganrog Art Gallery, Taganrog, Russia.

- Portrait Of A Nurse. Detail.

1907. Oil on canvas. 74 x 56 cm. Taganrog Art Gallery, Taganrog, Russia.