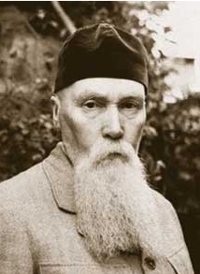

Nicholas Roerich Biography

Nicholas Roerich (1874-1947), in Russian: Nikolai Konstantinovich Rerikh, was a Russian painter of the first half of the 20th Century. Like many of his contemporaries (most prominently, Marc Chagall and Wassily Kandinsky), he left the country as a result of the Russian Revolution to live most of the rest of his life abroad, including nearly 20 years in India.

The massive body of work Roerich left behind -- numbering some 7000 paintings -- demonstrate well the diversity of his interests. His earlier works feature themes from the history of Russia, intermixed with subjects from the Russian Orthodox religion and Russian folk tales. Roerich was increasingly fascinated with the religion, culture and history of the Himalayas, so later works feature more Oriental themes, derived from both life and legend. All are interspersed with Roerich’s own spiritual beliefs and philosophy. A large part of the painter’s output were landscapes, most famously of the Himalayas, though he painted the countryside wherever he traveled, including many parts of Russia, Europe, the US, India, China, Tibet and Mongolia.

His style varies through the years as well, from a dreamy, relaxed style most similar to Impressionism, to Symbolism, to the bold, almost cartoon-like style that he is perhaps best known for, something intermediate between Expressionism, Art Nouveau and, of course, the indigenous art of the Indian sub-continent and the highlands of Central Asia. However one tries to pigeonhole Roerich's art, one thing remains clear: his style was unique and fully his own.

Roerich was born on October 9, 1874, in St. Petersburg, then the capital of the Russian Empire, into the family of a notary. His father, Konstantin (Constantine) Fedorovich Roerich, came from Swedish nobility that had settled in Russia some time in the mid-1700s. His mother, Maria Vasilievna, was descended from the prosperous Kalashnikov merchant clan. The Roerichs were well-educated and associated with many notable intellectuals of the period, including the chemist Dmitri Mendeleev, historians Konstantin Golstunskiy (1831-1899) and Nikolai Kostomarov (1817-1885) and the artist Mikhail Mikeshin (1835-1896), who became young Nicholas Roerich's first art teacher. This early exposure to many of his forward-thinking contemporaries fostered Roerich's life-long fascination with art, history and archaeology.

By the time he graduated from gymnasium (Roerich attended the Karl May Gymnasium in St. Petersburg), the young man had firmly decided to become an artist, much to the delight of Mikeshin. His father was opposed, but Roerich was stubborn enough to have his way.

Roerich studied law at the St. Petersburg University, attended lectures in the history department of the same, and took lessons at the Academy of Art. Kuindji was one of his teachers there, and greatly influenced him. Roerich later wrote that Kuindji was "not only a great artist, but a great Mentor". Roerich inherited from him the technique of the "emotional landscape". Also during his student years, Roerich joined the Russian Archaeological society.

Roerich saw the role of the painter as simultaneously that of an educator, whose function it was to shape society, and a mouthpiece, a means for society as a whole to express itself. His work from the 1890s consisted mainly of landscapes and themes derived from Slavic history and folklore. E.g. Ushkuinik, Pskovich, Ivan Tsarevich Finds a Decrepit Cabin (1894), Messenger (1897) and Gathering of the Elders (1898).

In 1895, the painter met Vladimir Stasov (1824-1906), the renowned music and art critic, who was also a scholar of Oriental folklore and literature. At the end of the 19th Century, many members of the Russian intelligentsia felt that Russian art followed Western tastes and trends too closely, and there was much interest in Russian and Slavic history, as well as Russia's connections with the cultures of the Orient. It was only natural that Roerich shared in the popular trend, but in him the interest blossomed to a life-long fascination.

After graduating from the St. Petersburg University in 1898, Roerich went to work for the Society for the Encouragement of Artists as an assistant to the director of the museum, and simultaneously as assistant to the editor of the new magazine "Art and the art industry" (Russian: Iskusstvo i hudozhestvennaya promyshlennost'). He published several articles in that magazine, and the equally new "World of Art" (Russian: Mir Iskusstva). He was also active as an archaeologist, heading several digs, the findings of which he presented annually before the Archaeological Society. He is the author of numerous books on the subject, and was considered one of the prominent Russian archaeologists of his day.

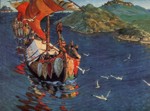

In 1900-1901, he visited Paris to further his artistic education under Fernand Cormon, who had, at different points in time, tutored Toulouse-Lautrec, Van Gogh and, in the 1890s, Borisov-Musatov. His painting style became bolder and crisper, showing the influence of the Art Nouveau and losing some of the softness that characterized his earlier works, though he stayed true to the Pan-Slavic themes of his work. E.g. The Ominous (1901), Foreign Guests (1901), Guests from Across the Sea (1902). He also tried his hand at interior decoration, painting friezes and designing furniture.

In 1901, shortly after his return from Paris, Roerich married Elena (Helena) Ivanovna Shaposhnikova (1879-1955), whom he had courted since 1899. They would stay devoted husband and wife until Roerich's death in 1947. The couple had two sons: Yuri (George) Roerich (1902-1960) and Svyatoslav Roerich (1904-1993). It was a result of his wife’s influence that Roerich began to develop an interest in Theosophy, an esoteric belief system established by Helena Blavatsky (1831-1891) in 1875, that was in vogue in Russia at the time. It would prove to be a major influence on the painter’s life and work.

During the 1900s, Roerich became friends with Diaghilev, Benois and the "World of Art" Society (Mir Isskustva). He exhibited with them several times though he never shared all of their ideals, especially political ones; he often refused to participate in political actions or sign petitions.

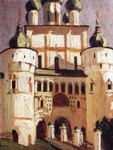

In the years 1903-1904, he traveled around Russia to study traditional Russian architecture, painting many old churches, kremlins and monasteries. A landmark work was the painting Treasure of the Angels, started in 1905 and first exhibited in 1911. Breaking for the first time with Slavic themes, the painting derived its inspiration from Indian and Tibetan folklore: it depicted the magic rock Shantamani, from which sprouts the tree of life.

In 1905, Roerich had his first exhibition outside of Russia, in Prague, where it was a sensation. Over the next two years, his works were shown in a number of European cities, including Vienna, Munich, Berlin, Venice and, most notably, the Autumn Salon in Paris, cementing his reputation in the West.

During the years 1906-1914, Roerich focused on monumental decorative projects. He painted murals, designed friezes and laid mosaics for churches, hospitals and other public buildings. Just a few examples of his work include his murals for the Church of the Veil of Our Lady in the village of Parhomovka in the Kiev Governorate, the church in the village of Morozovka, near Shlisselburg, and the church of the Moscow Life Guard Regiment in St. Petersburg; mosaics in the Cathedral of the Trinity located in Pochayevskaya Lavra in the Ternopil Governorate; frescoes for the St. Anastasia watchtower in Pskov and the Sepulchre of the Holy Spirit in Flenov, near Talashkin; friezes for the "Russia" society building in St. Petersburg; decorative panels for the chapel in the villa of L.S. Livshits in Nice, France (never delivered, due to the beginning of WWI). Unfortunately, many of these works did not survive the ravages of the two World Wars, the Russian Civil War, as well as years of neglect by the Soviet authorities.

In 1910, Roerich became chairman of the re-established World of Art society, which had been inactive since 1904, and worked in this capacity until 1913. He collaborated with Diaghilev on two productions by Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes: Prince Igor (1909) and Le sacre du printemps (1913); Roerich’s role was designing costumes and stage sets. It was during this time that the painter first wrote of his desire to visit India.

During the First World War, Roerich devoted himself to raising money for charity work, particularly welfare for wounded soldiers and their families. He also publicly advocated for the signing of an international treaty -- a "peace pact," as he himself preferred to call it, -- in which nations would agree to protect artistic and cultural sites and monuments during wartime, an idea he had floated as early as the Russo-Japanese War of 1904-05. Roerich's idea did not begin to gain support until well into the 1920s and 30s, culminating in the ratification of the Roerich Pact by ten nations, including the United States, in 1935. The Hague Convention for the Protection of Cultural Property that was adopted at the urging of UNESCO in 1954, seven years after Roerich's death, was based in large part on the Pact.

Through the 1910s, Roerich was increasingly interested in the meaning and symbolism of color. His ideas, if not his art, have much in common with those of his contemporary Wassily Kandinsky. Around this time, the Slavophile themes that characterized his earlier art began to be tempered by more universal spiritual and philosophical ideas. The bleak zeitgeist of the war and pre-war years finds reflection in many of these paintings: Sword of Courage (1912), The Last Angel (1912), Cry of the Serpent (1913 and 1914), The Doomed City, Human Works, Firelight (Zarevo), Crowns (all 1914), Arrows of the Sky - Spears of the Earth (1915), Pantaleon the Healer (1916). However, a poignant counterpoint is seen in the landscapes that Roerich painted in the Caucasus, Finland and in the Baltic states, at the time all parts of the Russian Empire.

In the years 1909-1915, Roerich, as one Russia’s foremost experts on Buddhism, was involved in the construction of a buddhist temple (or “datsan”) in St. Petersburg -- the Datsan Gunzechoinei. Despite the opposition of the Russian Orthodox Church, the first service was held in 1913 and the temple was officially consecrated in 1915. Unfortunately, the upheavals of the October Revolution and Stalin’s purges did not treat it well. The datsan was sacked during the Russian Civil War; at one point, it was used as a barracks for a detachment of the Red Army. It was briefly restored during the 1920s, only to be shut down again by the end of the decade. In the 1930s, all Buddhists in St. Petersburg were imprisoned or executed. However, the temple was fully restored in the early 2000s and today it is open to the public.

In 1916, Roerich rented a house in Karelia, an area of land on the border between modern-day Finland and Russia that is sparsely populated and remote, despite being only a short distance from St. Petersburg. Roerich intended for this to be a creative retreat, where he would be free from the stresses of his busy public life. Over the next two years, he divided his time almost evenly between the city and the countryside. The February revolution caught Roerich in St. Petersburg. Though a political moderate, the painter took the events in stride. He became member of a committee for the protection of artwork and historical artifacts. After months of intense work, Roerich retreated to his house in Karelia for a much-needed break. He was still there in May 1918 when Finland closed its borders and declared independence, cutting the painter off from his homeland. Roerich would not set foot in Russia for many, many years.

Mystical and philosophical themes abound in Roerich’s output of this period and can be seen in works such as Karelia - the Eternal Wait (1917), Holy Island (1917), The Messenger Cloud (1918), Eternal Horsemen (1918), The Prophetic Cloud (1921). As usual, he painted many landscapes.

As the situation in the Russian Empire degenerated further, Roerich was invited to travel to Stockholm by professor Oskar Bjork. There, the painter exhibited his works and gave talks. In 1919, he left for London, where he reunited with Diaghilev. In the fall of 1920, the painter travelled to the USA at the invitation of the Chicago Institute of Art. His first of a planned series of 30 exhibitions in the country took place on December 4, in New York City.

Roerich travelled widely in the United States. He was a particular admirer of the desert landscapes of the Southwest and was very interested in Native American artwork. He spent the summer of 1922 in the artists’ colony on Monhegan Island, Maine. Much of his artistic output from this time period includes landscapes, e.g. Song of the Waterfall and Song of the Crescent Moon (both 1920). It was at around this time that Nicholas and Helena Roerich began preaching the mystical philosophy of “Agni Yoga”, which they claimed was derived from the teachings of Oriental holy men and described as “The Teaching of Living Ethics”, and which was strongly inspired by Theosophy.

In the United States, Roerich found a warm reception not only for his art but also for his ideas regarding the importance of preserving and popularizing art, both of which were firmly linked in the mind of the artist. In 1921, he founded the international artists’ association Cor Ardens (Latin for “Blazing Hearts”), whose goal was to acquaint the American public with the contemporary art of the Old World. In 1922, this was followed by the founding of the international cultural center Corona Mundi (“Crown of the World”), which focused on the indigenous art of cultures and nations from around the world. Roerich found as well sponsors who were willing to finance a voyage to the Indian subcontinent, the artist’s long-cherished dream.

November 17, 1923 saw the inauguration of the Nicholas Roerich Museum in New York City. Nicholas Roerich, however, was already half a world away. On December 4, he, his wife and his two sons disembarked in Bombay, then part of British India.

The Roerichs headed north for a grand tour of the Indian Himalayas, stopping in Jaipur, Benares (modern-day Varanasi) and arriving finally in Sikkim, on the Tibetan border. The artist painted prolifically: to this relatively brief trip are attributed the Himalayas series, the “His Country” series and many, many other works.

Roerich returned to the USA towards the end of 1924 to report his findings, exhibit his works and secure support for a longer trip. In this he was successful and in 1925, the painter returned to India, this time travelling to Kashmir in the Northwest of India, and from there to the independent kingdom of Tibet, where he hoped to discover evidence supporting a theory popular among Theosophists, that Jesus Christ as a young man had travelled, lived and preached in Tibet.

His expedition made its way across Western Tibet, overwintered in the mountains and, in April 1926, arrived in Urumqi, in Western China, laden with artwork, and notes on their adventures and discoveries. From Urumqi, Roerich petitioned the Soviet government for a visa, which was granted, and on May 29 the Roerich expedition crossed the border into the USSR.

A conspiracy theory popular in Russia claims that Roerich was a Soviet spy and that his Tibetan expedition was both endorsed and funded by the USSR, who were interested in expanding their influence in Central Asia. The truth of the matter seems to be that any prominent public figure travelling across those strategically-sensitive regions was bound to arouse this kind of attention. So while American and British intelligence agencies speculated that Roerich might be working for the USSR, Soviet intelligence was worried about the opposite: that he was an American or British agent. Several documents from the Soviet archives that were released after the dissolution of the USSR suggest as much.

In either case, the artist was welcomed somewhat tepidly. In June, he arrived in Moscow by train, where he gave talks and exhibited the works that had been painted on the Himalayan crossing. A large number of these he gifted to the Soviet government. However, the painter did not tarry long, and in August his tracks once again led East. In August, he arrived in the Altai town of Verkhniy Uimon, which then, as now, was home to a colony of Old Believers, a heretical sect of the Russian Orthodox Church. Here, he painted one of his seminal works Belovodye (1926), literally meaning “White Waters”, this is a mythical land in Slavic mythology, akin to the Shambhala of Buddhist belief.

By September, Roerich was in Ulaan Baator, Mongolia, where he was forced to spend the winter, as the Central Asian mountains are completely impassable in the snow. His expedition set out again in April of the following year. The painter had requested permission to enter Lhasa, the capital of Tibet, which was closed to all foreigners except those who had the permission of the Dalai Lama. The Tibetan government vacillated. Though they were officially independent, they had to perform a careful balancing act to retain their independence from Britain, on the one side, and China, on the other. Roerich, whom rumor claimed to be a Soviet spy, was an unwelcome addition to the mix. Ultimately, the painter’s request was denied.

These proceedings caused a significant delay for Roerich’s expedition. Lacking the time to either return to Mongolia or proceed to India, they chose to spend the winter in the Himalayas. In the spring of 1928, the expedition arrived in Sikkim, British India.

The long journey, with its detours, served to make Roerich only more enamored with Asia and its mysteries. Exiled from his homeland, and without home or property anywhere else in the world, the painter decided to settle down in the foothills of the Himalayas. He ultimately purchased a home in the Kullu region of northern India. Here also, he founded the Urusvati Institute of Himalayan Studies to serve as his base of operations for future travels through the heart of Asia.

In 1929, Roerich made a trip to New York. The purpose of the trip was multifold. Firstly, the painter was at this time actively advocating his international “peace pact”, under which countries agreed to the protection of cultural relics and works of art in times of war. The United States would ultimately enter the pact in 1935. As mentioned previously, this treaty would become the basis for the 1954 Hague Convention for the Protection of Cultural Property, which is current international law governing these issues.

Secondly, Roerich brought over from India many of his new works, to be exhibited at the Nicholas Roerich Museum. Thirdly, the painter wanted to secure funding for his new institute and future travels in Central Asia. This last proved the most difficult task. With the stock market crash, there were many fewer rich patrons willing to sponsor Roerich’s artistic pursuits. The painter ultimately had his best luck in a somewhat unlikely place: the US Department of Agriculture, which was interested in crop plants and varieties that flourished in the harsh, dry climate of many parts of the Central Asian highlands.

With this new charter, Roerich set to work. Between 1929 and 1934, he led several journeys across the Great Mountain Ranges of Asia, at the end of each of which, he would ship paintings and samples back to New York.

His works from this period incorporate many South and Central Asian motifs, themes and styles. Mountains, of course, form an integral part of the opus. Paintings from this period include The Greatest and Most Revered Thang-La (1928-30), The Way to Shambhala (1933), Entry into Shambhala (1933-36). Roerich was also fascinated with indigenous rock art, which can be seen in works such as Gesar’s Sword (1932) and The Signs of Tessera (1932).

When he was not travelling, Roerich was re-visiting some old pursuits: theater decorations, e.g. his work on Stravinsky’s Eternal Spring (1929), and frescoes, e.g. the Agni-Yoga series (1928-1930).

In the latter half of the 1930s, Roerich travelled less and was less active in the public sphere. The painter had turned 60 in 1934, and came to prefer a slower pace to life. He was increasingly absorbed by theosophical ideas, and proselytizing his own esoteric philosophy of Agni Yoga. His art prominently featured the prophets of various religions who, according to theosophists, were all manifestations of one supernatural entity, “Maitreya”, which periodically appeared on Earth to guide mankind. Theosophists looked for commonalities among them, hence why, among other things, the theory that Jesus Christ had traveled to and lived in Tibet, for which Roerich had unsuccessfully searched for conclusive evidence. Paintings from this phase include The Way (1935-36), which featured Jesus, Buddha the Temptor (1927), Armaggedon (1935-36, and again 1940-41), Boris and Gleb (1942-43), who were the two missionaries that brought Christianity to Russia, and numerous portrayals of Sergey Radonezhsky (1932, 33, 35-36, 40), known in the Western tradition as Sergius of Radonezh, a monk, spiritual leader and one of the most venerated saints of the Russian Orthodox church.

In 1941, upon receiving news of Germany’s surprise attack on the USSR, Roerich organized an exhibition to benefit the Red Cross. Though the painter had distanced himself both mentally and geographically from Europe and its politics, the invasion of his homeland was painful to him. In 1945, after the Allies emerged from the war victorious, he editorialized: “In the distant Himalayas, we are overjoyed to hear that Great Rus’ is victorious.” The wording, with its reference to Russian nationalism, did not sit well with the leadership of the USSR.

After the war, the painter wanted very badly to return to his homeland, both out of nostalgia and to see what help he could provide in the reconstruction of the country. However, the tense relations between the USSR and the West prevented him from realizing this wish.

Nicholas Roerich died on December 13, 1947 at his home in Kullu, India. His last paintings were Lights on the Ganges (1947) and The Mentor’s Order (1947).

Bibliography

Messenger of Beauty: The Life and Visionary Art of Nicholas Roerich by Jacqueline Decter. Park Street Press, 1997.

Nicholas and Helena Roerich: The Spiritual Journey of Two Great Artists and Peacemakers by Ruth Abrams Drayer. Quest Books, 2007.

Nicholas Roerich by Manju Kak. Niyogi Books Pvt. Ltd, 2013.

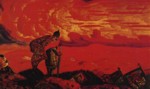

- Keeper Of The World.

1937. Tempera on canvas. 47 x 79 cm. Private collection. Moscow.

- The Messenger: Tribe Has Risen Against Tribe.

1897. Oil on canvas. 125 x 184 cm. The Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow, Russia.

- Old Russia, Rostov The Great. Entrance To The Kremlin.

1903. Oil on panel. 41 x 32. The State Museum of Oriental Art, Moscow, Russia.

- Foreign Guests. Series 'The Beginning Of Russia. Slavs.".

1901. Oil on canvas. The Kremlin Armory, Moscow, Russia.

- Dorje The Daring One.

1925. Tempera on canvas. 75 x 117 cm. Nicholas Roerich Museum, New York, NY, USA.

- Polovetsky Camp. Set Design For 1909 Production Of Borodin's Opera...

1908. Pastel, charcoal, gouache on paper mounted on cardboard. The Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow, Russia.

- Kiss To The Earth. Set Design For Igor Stravinsky's Ballet Le Sacre Du...

1912. Tempera on cardboard. 62 x 94 cm. The Russian Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia.

- Arrows Of Heaven. Spears Of The Earth.

1915. Tempera on cardboard. 103 x 188 cm. Turkmen Museum of Fine Arts, Ashgabat, Turkmenistan.

- St Pantaleon The Healer.

1916. Tempera on canvas. 130 x 178 cm. The Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow, Russia.

- Holy Island.

1917. Tempera on canvas. 49 x 77 cm.. The Russian Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia.

- Song Of The Waterfall.

1920. Tempera on canvas. 81.2 x 122 cm. Nicholas Roerich Museum, New York, NY, USA.

- The Greatest And Holiest Of Thang-La.

1928-29. Tempera on canvas. 97.1 x 61.6 cm. Nicholas Roerich Museum, New York, NY, USA.

- Gesar's Sword.

1932. Tempera on canvas. 76 x 117 cm. The Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow, Russia.

- Armageddon.

1935-36. Tempera on canvas. 91.4 x 122 cm. Svetoslav Roerich Collection, Bangalore, India.

- St Boris And St Gleb. Detail.

1942. Tempera on canvas. 61 x 123 cm. The Russian Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia.

- Lights On The Ganges.

1947. 82 x 137 cm. The Russian Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia.

- Idols. From "The Beginning Of Russia. Slavs" Series.

1901. Gouache on cardbord. 49 x 50 cm. The Russian Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia.

- The Ominous.

1901. Goasche, ink, pen, brush on paper mounted on cardboard. 25.2 x 45 cm The Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow, Russia.

- Town In Construction.

1902. Oil on canvas. 154.5 x 264.5 cm. The Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow, Russia.

- Old Russia, Yaroslav. Church Of The Nativity Of Our Lady.

1903. Oil on panel. 31.7 x 40 cm. The State Museum of Oriental Art, Moscow, Russia.

- Old Russia, Izborsk. Cross For Truvor Town Site.

1903. Oil on panel. 31 x 43.8 cm. The State Museum of Oriental Art, Moscow, Russia.

- Boats.

1903. Tempera on canvas. 165 x 170 cm. Museum of Fine Arts, Omsk, Russia.

- Rostov The Great.

1903. Oil on wood. 31.4 x 41 cm. The Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow, Russia.

- Resurrection Monastery In Uglich.

1904. Oil on panel. 46 x 83 cm. The Russian Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia.

- Ancient Life.

1904. Tempera on cardboard. 42.5 x 52 cm. The A. N. Radishchev Museum of Arts, Saratov, Russia.