Diego Rivera Biography

Diego Rivera (1886-1957) was a Mexican painter of the first half of the 20th Century and a collector of Pre-Columbian Mesoamerican art. He is most famous for his large murals, executed in the nascent Mexicanist style. He lived during a time of revolution and rising nationalism in his native country, when peasants and poor farmers of largely Native American and Mestizo ancestry sought to overthrow the land-owning Spanish Creole class that had ruled Mexico since it gained independence in 1821. This was accompanied by the birth of a brand of Mexican art that combined the influences of Pre-Columbian Native American culture with contemporary European trends. Rivera was a leading figure in this movemenet.

Early Life and Education

Jose Diego Maria Rivera-Barrientos, along with his twin brother Jose Carlos Maria, was born on 8 December 1886 (some sources say 13 December), in the city of Guanajato, Mexico. They were the two eldest sons of Diego Rivera and Maria del Pilar Barrientos. Both the parents were school teachers. The father was of Creole origin; according to rumor the painter's paternal grandfather had been born in Russia and immigrated to Mexico. Diego's mother was one-quarter Indian.

Diego's twin brother would die in infancy.

In 1892, the family moved to Mexico City, where Diego was sent to the Carpantier Catholic College.

Diego exhibited a vocation for painting early in life. In 1896, he began attending evening classes at the San Carlos Academy of Art. Two years later, he enrolled at the Academy full-time, despite the wishes of his father, who wanted a military career for his son. Diego studied under such painters as Santiago Rebull, Felix Parra and Jose Maria Velasco, his artistic education firmly grounded in classical principles.

In 1906, at the age of 20, Rivera exhibited his works for the first time, as part of the annual exhibition held by the San Carlos Academy.

Rivera's Artistic Development: Europe

In 1907, the governor of Veracruz granted the young painter money to travel to Europe, in order to further his artistic education, and in January 1908, Rivera left for Spain. While in Europe, Rivera experimented with a great variety of styles and techniques, emulating the old masters like El Greco and the painters of the Italian and Northern Renaissances, experimenting with Classicism and Impressionism, dabbling in the contemporary movements of Cubism and Post-Impressionism and finally settling on the simple, straightforward Realist style that would characterize most of his later work.

He stayed in Spain for more than a year. In 1909, he traveled to France, then visited England and Belgium, where he met the Russian artist and art teacher Angelina Beloff (Belova) who would become his mistress and companion for the next twelve years.

Some works of this period include: House over the Bridge (1909), Head of Breton Woman (1910) and Breton Girl (1910). These paintings show the strong influence of Rivera's formal academic education.

In 1910, Rivera exhibited at the Salon des Independents in Paris for the first time. In August of that year, he returned to Mexico, where he exhibited at his alma mater, the San Carlos Academy. His stay coincided with the outbreak of the Mexican Revolution, which would continue over the next two decades and play an important part in the painter's rise to prominence. In his memoirs, Rivera would later claim that he fought in the Revolution in the ranks of the Zapatistas, but this is highly unlikely, at best.

Just a few months after the exhibition, Rivera returned to Europe, spending the summer in Paris, and then traveling to Catalonia, in Spain. In 1912, he and Angelina moved into an apartment in Paris. That summer, the two of them stayed in Toledo. His work of the period shows the first signs of Cubist influences.

In 1913, his first Cubist works were shown at the Salon, demonstrating a much brighter palette and bolder paintwork than that of his fellow Cubists. In 1914, the artist held his first solo exhibition, shortly before the outbreak of the First World War. When the war began, he retreated to neutral Spain, spending some time on the island resort of Mallorca, and then Barcelona and Madrid.

In 1915, Rivera had his first exhibition in the United States, at the Modern Gallery in New York.

With the war dragging on, he returned once more to Paris, where he became one of the leaders of the "Classicist" Cubist group, which included artists such as Juan Gris, Gino Severini and Jean Metzinger. Angelina also introduced him to an intellectual circle that had collected around Henri Matisse and included many Russian expatriates.

It was here that he met and started a relationship with the Russian artist Marevna Vorobiev-Stebelska, whilst still maintaining his relationship with Angelina. The following year, Angelina gave birth to his son, also named Diego. The child would fall victim to the Spanish flu pandemic that swept through the world in the latter years of the war. In 1919, Marevna would give birth to a girl, Marika, who she claimed was Rivera's child. Rivera never acknowledged paternity, though he agreed to support his lover and her daughter financially.

In 1917, Rivera was employed by the Galerie "L'Effort Moderne," and it looked liked the artist would make an outstanding career as a Cubist. This was not to be, however. Rivera's Cubist work was disparaged by Pierre Reverdy, an influential Parisian art critic. Incensed, Rivera confronted Reverdy, and they came to blows. As a result, Rivera abandoned Cubism and changed his circle of friends completely.

Works of this period would include such diverse paintings as: View of Toledo (1912), Sailor at Breakfast (1914) and Zapatista Landscape -- The Guerrilla (1915).

In 1918, the Diego and Angelina moved to the Champ-de-Mars in Paris. His work of the period shows the influence of Post-Impressionism, particularly that of Cezanne. Little by little, the painter returned to figurative painting.

In 1919, Diego Rivera first met David Alfaro Siqueiros, another Mexican painter and a passionate Communist. The two discussed the need for the development of a unique Mexican style of art, based on the art of the pre-Colombian inhabitants of Mexico. Rivera's growth and maturation as an artist was coming to a climax.

In 1920 and 1921, Rivera traveled through Italy, admiring the art of the Renaissance. He was greatly impressed by the large and elaborate murals of the Italian masters, and this provided the final stroke in the development of the artistic style that he would be best known for.

After another brief stay in Paris, he finally returned to Mexico, breaking almost all contact with his European friends, girlfriends and children. He had lived in Europe for the better part of 14 years.

Return to Mexico and Rise to Prominence

Diego Rivera's return to his homeland coincided with the Mexican government adopting a policy of popular education, which included, among numerous other provisions, funding for the painting of murals in public places. After a period of familiarizing himself with indigenous Mexican art and experimentation, Rivera settled on a simple, realist style that made him ideally suited to the task.

In 1922, Rivera painted his first mural in the Mexicanist style, the Creation (1922-1923), decorating one wall of the Simon Bolivar Amphitheatre in the Escuela Preparatoria Nacional (National Preparatory School). The work espoused many of the ideals of the new Mexicanism movement: racial equality, with the figures in the fresco featuring all of Mexico's many racial groups; religious symbolism; and the unity of man and nature.

The mural was, unfortunately, dismantled a decade letter, under the Nationalist government of Plutarco Elias Calles.

Also that year, Rivera married Guadalupe Marin, who had been one of his models. They had their first child, a daughter whom they named Guadalupe, in 1924, and in 1927 they had their second daughter, Ruth.

During the same period of time, Rivera helped found the Union of Revolutionary Painters, Sculptors and Graphic Artists, and through this organization was first introduced to Communist ideology. Soon afterwards, he joined the Mexican Communist Party. It is questionable whether the artist was truly dedicated to Communism, or whether he was merely going along with his fellow artists. It is almost certain that he never read the works of Marx, let alone later Communist theorists.

In September of 1922, Rivera began work on a monumental wall-painting project: the decoration of the two inner courtyards at the new building of the Secretariat of Public Education (Secretaria de Educacion Publica or SEP). The artist's task was to paint -- with the aid of a team of assistants -- 117 frescoes, over a total surface area of more than 17,000 square feet (1,600 square meters). The project would take 6 years, and would only be finished in 1928 and is considered to be one of the painter's best works.

Some frescoes of the SEP project are Entry into the Mine (1923) The Maize Festival (1923-1924), The Sacrificial Offspring - Day of the Dead (1923-1924) and Good Friday on the Santa Anita Canal (1923-1924).

In 1925, Rivera began work on frescoes at the National School of Agriculture, at Chapingo. Here, he decorated the school's assembly hall in a manner that was not unlike Michelangelo's work in the Sistine Chapel, although Rivera rejected Christian symbolism and themes, employing instead a mix of Socialism with pre-Columbian Indian religion.

In 1927, he was invited to the Soviet Union as a member of the Mexican Communist Party, to take part in celebrations for the tenth anniversary of the October Revolution. Rivera had wanted to visit Russia since his Paris days and looked forward to the trip. However, the USSR would disappoint him, and the painter's unsound political views would disappoint the Soviets. After an initially warm reception and 9-month stay, the painter was asked to leave. Rivera's entire artistic output over the course of this period consisted of a few watercolor sketches.

Returning to Mexico in 1928, Rivera went back to work on the SEP project. At around this time, he met the art student Frida Kahlo, and this led him to paint what is perhaps the best-known mural of the SEP series: The Arsenal - Frida Kahlo Distributes Arms (1928). The fresco, which shows workers taking up rifles and bayonets, includes many of Rivera's friends and associates. In the center stands Frida Kahlo, dressed in the red shirt of the Mexican Communist Party (though she was not a member at the time). On the far left of the painting, it's possible to see David Alfaro Siqueiros, a fellow mural painter and dedicated Communist. On the right, Rivera depicted Julio Antonio Mella, one of the founders of the Cuban Communist Party, and Mella's companion Tina Modotti, an Italian-American who was a prominent Communist activist.

At this time, the political climate in Mexico was beginning to change and funding for murals was cut. Many mural painters, including David Siqueiros and Jose Orozco, left Mexico City for the provinces. Rivera, however, viewed as the principal figure of the mural painting movement, stayed on and managed to convince the government to allow him to carry through with the epic work at the SEP.

Later in 1928, Rivera requested a separation from his wife Guadalupe. He married Kahlo the following year.

1929 was a productive year for the painter. He painted murals down the walls of the stairwell at the National Palace and on the walls of the Ministry of Health, in Mexico City. At Cuernavaca, he was commissioned to paint a mural at the Palace of Cortes. He was also briefly appointed director of the upper classes at the San Carlos Academy of Art, but was soon dismissed by the leftist administration, which did not think him committed enough to its political ideals. That year, he left the Mexican Communist Party, unwilling to become embroiled in any sort of political struggle.

Work in the United States

The bloom of Mexican mural painting had attracted much attention in Mexico's northern neighbor, the United States, and Rivera received numerous invitations to travel there. As his brand of art fell out of favor with the increasingly rightist government at home, he decided to take advantage of the opportunity. Rivera would spend the next 4 years in the United States. In 1930, he stayed on the West Coast, working on murals for the San Francisco Pacific Stock Exchange and for the California School of Fine Arts. The following year, he moved to New York, where he held an exhibition at the newly opened Museum of Modern Art. This was only the second one-man exhibition in the museum history; the previous had been a Henri Matisse retrospective several years prior.

Initially, he was greeted enthusiastically by patrons and the public, but with suspicion by intellectuals and fellow artists, who correctly saw in him a very capable rival. Ironically, by the end of his stay in the United States, the opposite would be true: Rivera and his wife Kahlo would charm American art circles, while patrons would be turned away by the overtly socialist symbolism and ideology that Rivera incorporated into his work.

This did not prevent the artist painting what is considered one of his masterpieces, and one of the greatest works of 20th Century monumental art. This was the fresco series Detroit Industry, which the artist worked on between 1932 and 1933. Based on the observations that the artist had made at the Ford family factories, it celebrated the American industrial worker in the way that his earlier Mexican frescoes had celebrated the farmer. This would also be one of Rivera's most complete fresco series.

Many critics condemned the work for what they saw as its socialist and Communist themes. However, the Ford family, who had sponsored the paintings, defended the works and Rivera was allowed to complete it.

This was not the case with a mural that Rivera painted for the Rockefeller Center, in New York, just months after finishing Detroit Industry. The artist was asked to depict mankind striding towards a "new and better future". Rivera decided to incorporate portraits of Lenin and Trotsky into the work, which, understandably, did not sit well with his employers. The commission was cancelled and the unfinished mural taken down. However, Rivera did not abandon the idea and, in 1934, when he and his wife Frida returned to Mexico after the deposition of the Nationalist leader Calles, he re-painted the mural for the Palace of Fine Arts in Mexico City. This version was entitled Man, Controller of the Universe (1934).

Rivera's Peak Years

Rejected by both the Communist party and bourgeoisie of the United States, upon his return to Mexico in 1934, Diego Rivera was embraced by Mexico's new moderate government, and he gradually began to settle down.

He fulfilled several murals for government buildings, including the fresco series Epic of the Mexican People for the National Palace in Mexico City. The work had been commissioned as early as 1929, but Rivera had left it unfinished when he departed to the United States. The series included Pre-Hispanic Mexico -- The Early Indian World (1929), History of Mexico from the Conquest to 1930 (1929-1931) and Mexico Today and Tomorrow (1934-1935). Though less expansive than some of his other works, the National Palace murals are considered among his best.

During this time, Rivera began to paint extensively in his studio, producing work in many different genres, but particularly portraits of "typical" Mexicans, as well as numerous landscapes. These works were very popular with tourists, and the painter's financial standing improved substantially. He used the money to start building a collection of Pre-Columbian Mexican art.

Soon after his return from the United States, Rivera came under fire from fellow muralist Siqueiros and the Mexican Communist Party, who denounced him as a traitor of their cause. In 1936, the painter publicly declared that the cause for his break with the Communist party were its increasingly Stalinist views, which he did not agree with.

That year, he petitioned the Mexican government to grant political asylum to Leon Trotsky, who had been kicked out of Norway because of pressure from the USSR. The Mexican government acceded to the request, on condition that Trotsky would refrain from political activism and, in 1937, Trotsky and his wife Natalia Sedova moved in with Rivera and Kahlo. It turned out, however, that Rivera's political views were no more Trotskyist than they were Stalinist. The Bolshevik leader and Rivera had an ideological falling out and, in 1939, Trotsky and his wife moved out. Rivera and Kahlo, who sympathized with Trotsky, divorced. Trotsky would be assassinated a short time later.

Rivera and Kahlo were unable to keep apart for long, and they re-married less than a year later.

In 1940, Rivera again visited the United States. Though he had been deeply hurt by the rejection of his Rockefeller mural, he was reconciled somewhat by the fact that the United States were vehemently opposed to fascism -- as the artist himself was. In fact, this formed the subject of a series of frescoes he painted for the Golden Gate International Exposition in San Fransisco: Pan-American Unity (1940). This series featured and eclectic jumble of elements of modern life in both the United States and Mexico, figures and events from the histories of these two countries and symbolism borrowed from Pre-Columbian Indian art.

This was the high point of the Diego Rivera's career, with lucrative commissions coming in as fast as he could fulfill them, and his renown in intellectual circles at a peak.

In 1941, Rivera began the construction of the Anahuacalli, a museum to house his private collection of pre-colonial Mexican art and relics. Rivera had had a fascination with Pre-Colombian Native American culture for some time, and seeking a way to exhibit his growing collection, decided that a stone building, modeled after the Aztec pyramid at Tenochitlan would make fitting housing. The Anahuacalli became something of the artist's child and hobby, into which he would invest much time and money throughout the remainder of his life.

In 1943, he became one of the first members of the National College, and conducted a number of conferences on politics, science and art. He was also given tenure as professor at the La Esmeralda College of Art. In 1947, with fellow mural painters Jose Clemente Orozco and David Alfaro Siqueiros, he founded the National Institute of Fine Arts' Commission for Mural-Painting.

During this time, he had painted fresh murals for the National Palace (1941), murals for the National Institute of Cardiology (1943) and a large-scale mural for the Hotel del Prado (1946), among other works.

In 1949, the artist celebrated the fiftieth anniversary of his painting career with a large exhibition at the Palace of Fine Arts. The following year, he was awarded the National Prize for Plastic Arts by the Mexican government. Together with Siqueiros, Orozco and Rufino Tamayo, he represented Mexico at the Venice Biennale.

Later Years and Death

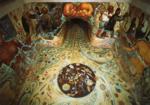

In 1951, Rivera undertook a new type of project. He was asked to execute a series of underwater murals at the Carcamo del Rio Lerma waterworks in Chapultepec Park in Mexico City. The title of the work was Water, Origin of Life, and Rivera had not done anything similar neither before, nor after.

The chief problem was the medium. The work was done around the edges and along the bottom of a pool, and would be underwater most of the time. After some experimenting, Rivera settled on a technique that used polystyrene in conjunction with colored rubber solution. On one side of the pool, Rivera depicted a female figure; on the other, a male figure. From these flows water, teeming with all forms of life: fish, crabs and lobsters, mollusks, amphibians and plants. At one end, where the pipe bringing water into the pool was connected, he depicted humans digging a well, and distributing cups of water to thirsty figures around them. On the fourth side, Rivera showed water being used by people for agriculture and recreation. Outside the waterworks, Rivera laid out the mosaic for a large fountain.

This would turn out to be one of his last outstanding public decoration projects.

In 1953, he executed murals for the Teatro de los Insurgentes, the Olympic Stadium on the campus of the Mexico University and the La Raza Hospital at the Mexican Institute of Social Security. These would be his last monumental public works, as the artist, 67 by this time, was growing too frail for this kind of work. Many of his works of the 50s were done in the studio, and include a large number of portraits.

In his latter years, and under the influence of his wife, the painter once again turned to Communism and this can be glimpsed in some of his work. He re-applied for membership to the Mexican Communist Party several times, but was rejected. In 1952, he sparked controversy with a "portable fresco" intended for the traveling exhibition Twenty Centuries of Mexican Art, which was to make a tour of Europe. The portraits of Stalin and Mao Ze Dong that he included in the painting made it unsuitable for the anti-Communist attitudes prevalent on the Continent at the time, and it was presented as a gift to the People's Republic of China, instead.

Rivera's wife Frida Kahlo died in 1954, ending a relationship that, while never stable, was, ultimately, loving. Stricken by her death, the artist made ready for his own. He presented Kahlo's "Blue House" and his own "Anahuacalli" to the Mexican government to be made into museums, and wrote a will and testament, expressing his wish to have his ashes mixed with those of Kahlo, after his death.

Shortly thereafter, Rivera was finally allowed to re-join the Mexican Communist Party. In 1955, the painter was diagnosed with cancer and he traveled to the Soviet Union for treatment. The result of this trip was the painting May Day Procession in Moscow (1956).

Diego Rivera died in Mexico City in 1957, of a stroke. His will was not honored, and he was buried in the Rotunda of Famous Men in the Civil Pantheon of Mourning. His studio was turned into a museum.

Bibliography

Mexican Muralists: Orozco, Rivera, Siqueiros by Desmond Rochfort. Chronicle Books, 1998.

My Art, My Life: An Autobiography by Diego Rivera with Gladys March. Dover Publications, 1992.

Diego Rivera by Pete Hamill. Harry N. Abrams, 2002.

Diego Rivera: A Retrospective by Linda Banks Downs, Cynthia Newman Helms. W. W. Norton & Company, 2002.

Dreaming with His Eyes Open: A Life of Diego Rivera by Patrick Marnham. University of California Press, 2000.

Diego Rivera: The Detroit Industry Murals by Linda Bank Downs. W. W. Norton & Company, 2000.

The Fabulous Life of Diego Rivera by Bertram D. Wolfe. Cooper Square Press, 2000.

Diego Rivera, The Complete Murals by Luismartin Lozano, Juan Coronel Rivera. Taschen, 2007.

- Portrait Of Angelina Beloff.

1909. Oil on canvas. Collection of the State of Veracrus, Xalapa, Mexico.

- Land And Freedom.

1923-24. Fresco. Ministry of Education, Mexico City, Mexico.

- Head Of A Breton Woman. / Cabeza De Mujer Bretona.

1910. Oil on canvas. 129 x 141 cm. Museo Casa Diego Rivera, Guanajuato, Mexico.

- Breton Girl. / Muchacha Bretona.

1910. Oil on canvas. 100-80 cm. Museo Casa Diego Rivera, Guanajuato, Mexico.

- View Of Toledo. / Vista De Toledo.

1912. Oil on canvas. 112 x 91 cm. Fundación Amparo R. de Espinosa Yglesias, Puebla, Mexico.

- Sailor At Breakfast. / Marinero Almorzando.

1914. Oil on canvas. 117 x 72 cm. Museo Casa Diego Rivera, Guanajuato, Mexico.

- Zapatista Landscape.

1915. Oil on canvas. Museo Nacional de Arte, Mexico City, Mexico.

- Creation. / La Creación.

1922-23. Fresco in encaustic and gold leaf Anfiteatro Simón Bolívar, Escuala Nacional Preparatoria, Colegio de San Ildefonso, Mexico City, Mexico.

- Entry Into The Mine. /Entrada A La Mina.

1923. Fresco. 4.74 x 3.66 m. East wall. Court of Labour, ground floor, Ministry of Education, Mexico City, Mexico.

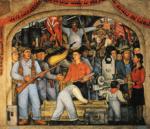

- From The Cycle: Political Vision Of The Mexican People (Court Of...

1923-24. Fresco. 4.38 x 2.39 m. Ground floor, south wall wall. Ministry of Public Education, Mexico City, Mexico.

- From The Cycle: Political Vision Of The Mexican People (Court Of...

1923-24. Fresco. 4.15 x 2.37 m. Ground floor, south wall wall. Ministry of Public Education, Mexico City, Mexico.

- From The Cycle: Political Vision Of The Mexican People (Court Of...

1923-24. Fresco. 4.56 x 3.56 m. Ground floor, west wall wall. Ministry of Public Education, Mexico City, Mexico.

- From The Cycle: Political Vision Of The Mexican People (Court Of...

1928. Fresco. 2.03 x 3.98. Second floor, south wall. Ministry of Education, Mexico City, Mexico.

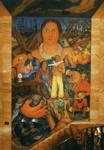

- The History Of Mexico - The Ancient Indian World.

1929-35. Fresco. North wall, National Palace, Mexico City, Mexico.

- The History Of Cuernavaca And Morelos - Crossing The Barranca. Detail.

1929-30. Fresco. Cortez Palace, Cuernavaca, Mexico.

- Allegory Of California. / Alegoria De California.

1930-31. Fresco. Mural on wall and ceiling of main staircase between tenth and eleventh floors. Exchange's Luncheon Club/City Club, Pacific Stick Exchange Tower, San Francisco, CA, USA.

- Detroit Industry.

1932-33. Fresco. The Detroit Institute of Arts, Detroit, Michigan, USA.

- Man, Controller Of The Universe.

1934. Fresco. Palacio de Bellas Artes, Mexico City, Mexico.

- The History Of Mexico.

1929-35. Fresco. West wall, detail of central arch, National Palace, Mexico City, Mexico.

- The History Of Mexico - The World Of Today And Tomorrow.

1929-35. Fresco. South wall, National Palace, Mexico City, Mexico.

- Dream Of A Sunday Afternoon In Alameda Park.

1948. Fresco. Museo Mural Diego Rivera, Mexico City, Mexico.

- The Hands Of Nature Offering Water. / Manos De La Naturaleza Bridando...

1951. Ground and four wall surfaces. Fresco in polystyrene and rubber solution. Carcamo del rio Lerma, Chapultepec Park, Mexico City, Mexico.

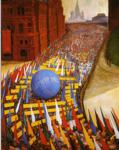

- May Day Procession In Moscow. / Desfile Del 1.De Mayo En Moscu.

1956. Oil on canvas. 135.2 x 108.3 cm. Private collection.

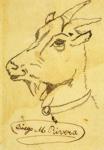

- Head Of A Goat. / Cabeza De Cabra.

c.1905. Pencil on paper. 12.5 x 9.5 cm. Rafael Coronel Collection, Cuernavaca, Mexico.

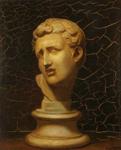

- Classical Head.

1898. Oil on canvas. 48.5 x 39.2 cm. Museo Casa Diego Rivera, Guanajuato, Mexico.