Niko Pirosmani Biography

Niko Pirosmani (1862? - 1918) was a Georgian Primitivist painter of the turn of the 20th Century. Without any formal education in art or, in fact, much of an education in anything, he made up for this with innate talent and the fecundity of his brush. Over the course of his brief life (he died at the age of 56), much of which passed in poverty and vagrancy, and working with only the cheapest materials, Pirosmani produced an immense number of paintings, a large chunk of which are lost. The artist's work came to public attention only towards the end of his life, almost by accident, and he had only a handful of exhibitions.

Niko Pirosmani was born in the small village of Mirzaani, Kakheti, Eastern Georgia, probably in 1862, though the exact date is uncertain. His surname in the original Georgian was Pirosmanshvili (alternately spelled Pirosmanshvilli, Pirosmanshwili and Pirosmanshwilli), though he became better known abroad by the dimunitive Pirosmani. The painter had three siblings: his sister Miriam, his elder brother Georgiy and his sister Peputsa, the youngest in the family.

Soon after Niko's birth, the family moved to the village of Shulaveri, not far from Tiflis (modern-day Tbilisi), where his father Aslan Pirosmanshvili had found work as a caretaker on the estate of the merchant Eprosin Kalantarov, an Armenian from Alaverdi who had settled in Georgia.

When Niko was six, a series of disasters struck the family. In 1868, his elder brother Georgiy died. In 1870, this was followed by the death of both parents, first the father, Aslan, and then the mother, Tekleh. The elder sister, Miriam, was married and lived in the Pirosmanshvilis' native Kakheti region. The younger sister, Peputsa, was taken in by relatives from back home. This left Niko, aged eight, with nowhere to go.

He was taken in by his late father's employer, Kalantarov, who, himself, had three sons and three daughters. Niko lived in the home of his adoptive parents, at first in the village of Shulaveri, but later in their Tiflis residence, for roughly the next 15 years.

The Kalantarov household could not have been more different from the poor conditions to which Niko had been used to in the home of his peasant parents. He was taught to read and write, both in Georgian and Russian. The Kalantarov's took him to church, to the theater and the opera. His artistic inclinations were discovered early on and he was encouraged to draw and paint.

Although Niko's adoptive family took good care of him, the future painter was treated not as another child, but rather as an overgrown family pet. There were always many children in the Kalantarov house, both their own and their numerous nieces and nephews, and Niko remained their constant friend and nurse-maid far past the age at which he should have learned a trade and become an independent individual. Indeed, it is rather puzzling why the Kalantarovs did not seek to find some employment for their ward. It is likely that much of Niko's later erratic behavior and personal problems were owed to these lapses in his upbringing. On the other hand, it is hard to guess what would have happened to the painter's talent and artistic drive if his life had turned out differently.

At one point, Niko showed his work to an artist, Gevork Bandzhagian, who praised the youth's efforts and advised him to take lessons. However, the Kalantarovs would not spend the money to fund the young artist's education. Instead, Niko, already in his late teens was placed as apprentice in printer's shop. The apprenticeship, however, lasted for only a few months. Pirosmani, who was used to the easy life he had enjoyed with the Kalantarovs, did not take well to the rigors of apprenticeship and ran away.

He found shelter in the house of the Kalantarovs' widowed daughter Elisabed (Elizabeth). After some time, Pirosmani proposed marriage. This was taken as a tasteless joke and he was kicked out. Indeed, in Georgia, where it was customary to maintain a distance between men and women, the very fact that Pirosmani -- by this time an adult -- was allowed to live under the same roof as his adoptive sister indicates that no one in the Kalantarov family viewed him as a grown man in his own right. After this unfortunate incident, the future painter was taken in by Kalantar, one of Kalantarov's sons.

In the second half of the 1880s, he attempted to start a painting and decoration shop in Tiflis together with Gigo Zaziashvili, an artist. This venture did not fare well, as Tiflis had a large number of established painters and decorators at the time and Pirosmani's enterprise was still-born. It seems that the painter had an unrealistic perception of the world around him and his place in it.

Finally, in 1890, he went to work for the railroad where he was assigned to be a brake operator. In the mountainous Caucasus, every wagon on the train had an individual brake in order to prevent the train from accelerating or even de-railing when going downhill. It was Pirosmani's job to work the brakes on his wagon when he received the signal. Since this was an undemanding task, and since a brake operator's platform was located on the exterior of the wagon, this gave him the opportunity to see much of Georgia's scenery, with its mountains, lakes, villages and people. These experiences are reflected clearly in his art, especially scenes of rural life.

Again, Pirosmani did poorly at this job. He was frequently late, sometimes failed to show up for the train at all and was fined a number of times for ignoring the orders of his superiors. He often filed requests to be transferred to different sections of the railroad and applied for leave to visit relatives and sick leave. In 1894, at long last, he quit the job, though it remains unclear whether this was mostly his own decision or whether this was done under pressure from his employers. It was probably a combination of the two.

Immediately afterwards he opened a stall in Tiflis, selling milk, matsoni (a Georgian yogurt-like product), cheese and butter. This business venture turned out to be more successful than his previous ones and, quite soon, the painter was renting a small shop, which he fully decorated himself, both inside and out. Getting bored with the work, he found himself a partner, Dimitra Alugishvili, who took over the day-to-day operation of the business. Pirosmani, meanwhile, remained as erratic as ever, often abandoning the shop without warning and talking on random walks through the town. He loved listening to street musicians, especially barrel organ players (see the painting Barrel Organ Player). Neighbors also attested that the eccentric artist would purchase freshly-mown hay, spread it on the floor of his house and roll in it, enjoying its distinctive countryside scent.

It was at this point in his life that he began to paint regularly, using one of the shop's back rooms as his studio. He painted a portrait of Dimitra, who, uncertain of what to do with the product, hid it away and eventually got rid of it.

Learning of Pirosmani's improved status, his relatives in Mirzaani restored contact with him. His brother-in-law came to visit him with ideas for further business ventures. Despite the protests of Alugishvili, who was very loyal to Pirosmani and their company, even though the painter's eccentricities probably made working with him difficult in the best of times, Pirosmani went along with many of the suggestions offered by the brother-in-law.

Not much is known about the next few years in Pirosmani's life. For several, quite extensive periods of time, he stayed in Mirzaani. He used his new-found wealth to construct his sister a house -- today, this is the Pirosmanshvili Memorial Museum. There was talk for a time of the painter taking a wife, but for obscure reasons, this never occurred.

In 1899, Pirosmani's relatives persuaded him to invest money into expanding his business beyond dairy products, against the wishes of Alugishvili. The venture failed and this led to a falling out between Pirosmani and his family. The details are uncertain, but the next time his brother-in-law came to visit him in Tiflis, the painter attacked him with a knife. Though no harm was done, this made the break between Pirosmani and his relatives final.

In fact, it seems that the painter's fiery temperament and erratic behavior estranged him from many of his neighbors. He was often described as unpredictable, flying into a rage at the slightest offense, whether real or perceived, and often attempting to rectify matters with his fists. Even by the standards of the people of the Caucuses, famously hot-headed and freer with their feelings than Western people, this was unacceptable. There is evidence that Pirosmani drank much during this time. Several times, he spoke of seeing visions of St. George, whom he described as his guardian-angel, standing over him with a whip in his hand. After the death of Alugishvili's daughter, Maria, Pirosmani's god-daughter, from disease, the painter was convinced that it was his fault for bringing ill luck into the house.

In the summer of 1900, the artist left his home and went missing for several months, returning only in the fall. Alugishvili was forced to take over the running of the shop -- admittedly, business went better as a result. When Pirosmani finally returned, his partner, still retaining loyalty to the enterprise's founder, offered him a generous stipend of a ruble a day (this was a not insubstantial sum of money, and more than enough for Pirosmani to support himself comfortably).

Pirosmani began a life of half-vagrancy. He would spend days on end lounging around Tiflis' central train station. Doubtlessly, he had friends there from his days of working for the railroad. Furthermore, the station, with its large amount of human traffic, provided Pirosmani with the visual stimulation he needed for his art. He painted more than ever during this time, drawing the portraits of his drinking buddies, producing thematic artwork for passers-by, painting murals or decorating storefronts and signs, often for no more reimbursement than free meals and drinks.

In fact, were it not for pure chance, Pirosmani might have forever remained in obscurity. What happened was this: in 1912, the brothers Zdanevich, Ilya and Cyril (Kirill), both painters who identified with the Futurism movement, came to Tiflis in search of "naïve" artists: self-taught and untainted -- as they saw it -- by academic education. The two brothers were of Georgian descent themselves, though they had been educated in Russia and France, and were great enthusiasts of the Primitivist movement that was gaining recognition and popularity in Western Europe, with artists such as Henri Rousseau.

One evening, the Zdaneviches happened to dine at a Tiflis tavern known as the Varyag (literally, "The Viking"; this was the name of Russian Imperial warship, after which the tavern was re-christened). Inside, they found the walls decorated with paintings by an anonymous local artist, done with little professionalism but with great vigor. This was exactly what they had been looking for. The Zdaneviches had stumbled across Pirosmani's artwork.

Still, as Pirosmani had no permanent place of residence and the brothers were only visiting briefly, it would be nearly a year before the young artists would meet their new-found idol in person. In January 1913, Ilya Zdanevich managed to track Pirosmani down to the tavern where he was staying temporarily, paying for his food and board with his artwork. The two conversed. Pirosmani was struggling with poverty and knew nothing of developments in the artistic avant-garde. However, when Ilya spoke of exhibiting his art, the painter became interested. Ilya ended up commissioning his portrait from the artist, which furnished him with a reason to return frequently. Over the next few weeks, Ilya would meet with Pirosmani almost every day. He attempted to interest others -- artists, journalists and critics -- in the painter's life and work and, at the same time, set about collecting Pirosmani's artwork from restaurants and taverns in preparation for an exhibition.

In March of 1913, Pirosmani's paintings were shown in Moscow at the "Target" exhibition (Russian:'Mishen'), organized by the Russian Futurists. The Futurists rejected all tradition in art, which they saw as undeserved worship of the past, and so, in addition to their own works, the Target exhibition included Russian and Cental Asian folk art, work by self-taught "naïve" artists such as Pirosmani, and children's paintings. This exhibition, combined with several articles published about him, succeeded in sparking interest in the painter, particularly among Georgians living in Russia.

Most of this came as too little, too late, for Pirosmani. Unaware of his growing recognition in artistic circles, he continued to live as a half-vagrant. Friendly tavern-keepers -- and Pirosmani was well known in that layer of society by this point -- would offer him free lodging -- usually in cellars --, and food and drink, in exchange for his artwork. This lifestyle was taking its toll, however, on both the painter's health and mindset. He was an individual disillusioned with life and with few hopes or aspirations.

The outbreak of World War I brought many Georgian intellectuals that had been living in France, Germany and Russia back to their native land, leading to a great revitalization of cultural life in Tiflis. Just as the young Modern painters in Paris were the first to recognize the artistic merit of Primitivist Henri Rousseau, so Georgia's young artists were the first to appreciate Pirosmani. In 1916, an exhibition dedicated entirely to him was organized in Tiflis.

Later that year, when the artists of the city came together to form the Society of Georgian Painters, one of their first decisions was to find Niko Pirosmani and bring him out of obscurity. To many of them, he was one of the few truly Georgian painters, uninfluenced by the West, and thus it was a matter of almost national pride. Two hundred rubles were ear-marked for the painter "should he be found still alive".

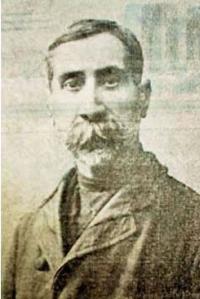

A few weeks later, the painter was found and brought to a meeting of the society. From the description of Lado Gudiashvili, a young Georgian artist: "Niko Pirosmani was tall, his graying hair was brushed back. His pale face expressed a natural softness and calm, interspersed with a great sadness. His beard was trimmed and his mustache drooped downwards. He was wearing a grey jacket and thick, dirty, paint-smeared pants. In one word, before us stood a man from the lowest station of society, broken and crushed by a life of vagrancy and drunkenness."

An important outcome of this meeting was that the painters, headed by David Shevardnadze, escorted Pirosmani to a photographer, where they took one of the artist's only extant pictures. After this, and despite the urgings of Society members, Pirosmani left and disappeared again.

Meanwhile, interest in him was only increasing. Several newspaper and magazine articles about him came out and one magazine published criticism and caricatures -- ridicule always being a sure sign of success for any artist. Pirosmani, however, had not a care for any of this.

In 1917, Lado Gudiashvili came looking for him again with more money from the Society. He found Pirosmani living in a tavern's storage room, with only a few planks for a bed. He later made a note of how sickly the artist looked.

Pirosmani's last days passed in obscurity. In the spring of 1918, he stumbled into the cellar of one of his old friends, the shoemaker Archil Maisuradze, and fell asleep on the stone floor. He was already very sick. Maisuradze discovered him there only several days later, by which time the painter was fevered and delirious. Pirosmani was immediately rushed off to the nearest hospital, but it was far too late. He died only a day later, on April 7. The artist had neither any property nor next of kin that would claim him, and even the site of his grave in Tiflis is unknown.

Bibliography

Biography by Yuri MataevBiography by Yuri Mataev

- Barrel Organist.

Oil on oilcloth. State Art Museum of Georgia, Tbilisi, Georgia.

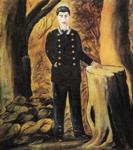

- Portrait Of Ilya Zdanevich.

1913. Oil on oilcloth. Private collection.

- Feast With Barrel Organist Datico.

1906. Oil on oilcloth. State Art Museum of Georgia, Tbilisi, Georgia.

- Portrait Of Alexander Garanov.

1906. Oil on oilcloth. State Art Museum of Georgia, Tbilisi, Georgia.

- A Georgian Woman With Tambourine.

1906. Oil on oilcloth. State Art Museum of Georgia, Tbilisi, Georgia.

- The Feast Of Five Princes.

1906. Oil on oilcloth. State Art Museum of Georgia, Tbilisi, Georgia.

- The Russian-Japanese War.

1906. Oil on oilcloth. Private collection.

- Hunting Scene With A View Of The Black Sea.

1912. Oil on oilcloth. State Art Museum of Georgia, Tbilisi, Georgia.

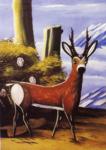

- Roe With A Landscape In The Background.

1913. Oil on oilcloth. State Art Museum of Georgia, Tbilisi, Georgia.

- Wedding In The Old-Time Georgia.

1916. Oil on oilcloth. State Art Museum of Georgia, Tbilisi, Georgia.

- Mother Bear With Her Cubs.

1917. Oil on oilcloth. State Art Museum of Georgia, Tbilisi, Georgia.

- A Boy Carrying Food.

Oil on oilcloth. State Art Museum of Georgia, Tbilisi, Georgia.

- Rooster And Hen With Chickens.

Oil on oilcloth. State Art Museum of Georgia, Tbilisi, Georgia.

- Threshing Yard. Evening.

Oil on oilcloth. House-Museum of N. Pirosmanashvili, Mirzaani, Georgia.

- Cook.

Oil on oilcloth. State Art Museum of Georgia, Tbilisi, Georgia.

- Gate-Keeper.

Oil on oilcloth. State Art Museum of Georgia, Tbilisi, Georgia.

- Feast In A Gazebo.

Oil on oilcloth. State Art Museum of Georgia, Tbilisi, Georgia.