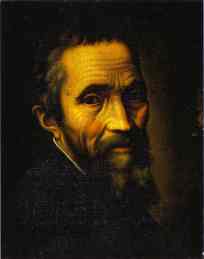

Michelangelo Biography

Michelangelo is certainly one of the most representative artists of the XVI century: a sculptor, painter, architect, and poet; a true Renaissance man in the best tradition of his contemporary, Leonardo da Vinci. He lived to a great age, and enjoyed great fame in his lifetime. Titian, and Venetian painting generally, was very much influenced by his vision, and he is responsible in large measure for the development of Mannerism.

Michelangelo di Ludovico di Lionardo di Buonarroti Simoni was born in 1475, in a village called Caprese Michelangelo, in the Casention area of Arrezo province, Tuscany, Italy. His father was Lodovico di Leonardo di Buonarotti di Simoni, a local magistrate; his mother was Francesca di Neri del Miniato di Siena. His family, the Buonarroti di Simoni, were descendants of the Countess Matilda of Tuscany, and considered minor nobility. They are mentioned in the Florentine chronicles as early as the XII century. However, Michelangelo's parents spent little time with him, and he spent much of his childhood with a sculptor and his wife in the town of Settignano, where his father owned a marble quarry.

It was thus quite natural that the young Michelangelo would want to pursue a career in art, despite his father's vehement, and sometimes violent, opposition to the idea. In 1488, at the age of 13, Michelangelo entered the workshop of Domenico Ghirlandaio, which speaks highly of his budding talent, as Ghirlandaio was by this time an established and well-known painter, and could afford to be picky with his apprentices. Thus, Michelangelo came under the indirect influence of Masaccio, as Ghirlandaio borrowed liberally from Masaccio's subjects, compositions and design elements. After less than a year, on Ghirlandaio's recommendation, Michelangelo transferred to the academy set up by Lorenzo the Magnificent. From 1489 till 1492, he lived in the Palazzo Medici in Via Larga, where he could study "antique and good statues" and socialize with the sophisticated humanists and writers of the Medici circle, such as Pico della Mirandolla, Marsilio Ficino and Angelo Poliziano.

Two notable works from this period are Madonna of the Steps (1490-1492) and Battle of the Centaurs (1491-1492).

Lorenzo the Magnificent died in 1492, and in 1494 the Medici were expelled from Florence. Under the brief rule of the priest Savonarola, whose ascetic religion and republican ideas influenced the young man deeply, Michelangelo was treated somewhat coldly because of his association with the Medici. However, he was allowed to continue with his work.

In 1494, Michelangelo left Florence and travelled first to Venice and then to Bologna, where he studied the cities' art and culture. In 1496, he arrived in Rome and stayed there until 1501. He returned to Florence briefly several times during this period but never permanently, alarmed by the city's political and economic instability.

Between 1497 and 1499, he carved the Pieta for the Vatican, one of his most famous works. Considered by contemporaries (and many critics throughout the centuries) the perfect union of Christian emotion with classical form, the sculpture would bring him widespread recognition and fame.

Returning, now widely acclaimed, to Florence in 1501, Michelangelo was commissioned by the new republican government to carve a colossal David, as a symbol of resistance and independence. Arguably his most famous work, the statue would cement his reputation as an extraordinary sculptor.

In 1504, the Signoria of Florence commissioned Leonardo da Vinci and Michelangelo to paint the walls of the Grand Council Chamber in the Palazzo Vecchio, Florence's seat of government. Leonardo worked on the Battle of Anghiari and Michelangelo on the the Battle of Cascina. Florence was immediately divided into two camps passionately supporting one or the other of the two famous painters. However, neither work was finished. Michelangelo's went no further than sketches for the final painting, which were destroyed in 1512 during a civil upheaval.

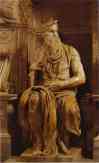

In 1505, Michelangelo was summoned by the new Pope Julius II to Rome and entrusted with the design of the Pope's tomb. The grandiose project was never completed. Although only 3 of the 40 commissioned figures were executed (Moses, Rebellious Slave (unfinished), Dying Slave), this commission dominated most of the rest of the artist's life. Michelangelo finally abandoned the constantly interrupted project only in 1547, 40 years and five revised contracts later. The final results can be seen at San Pietro in Vincoli, Rome. Victory and Crouching Boy were two other sculptures carved for the tomb, though they were never incorporated into the final version.

In 1508, Julius ordered the artist to paint the Sistine Chapel ceiling. Michelangelo accepted the commission, but from the beginning considered Pope Julius' vision too simple and limited. At the time, it was highly unusual for a patron to allow his plans to be completely changed by an artist. In this case, moreover, the changes meant that the work would feature entirely different subjects and different composition from the original plan.

As Michelangelo was not very familiar with the technique of fresco, he was forced to call in several Florentine painters for consultation. Ultimately, however, he did all the work himself, which was unprecedented on a project of such magnitude as the Sistine Chapel. It would have been normal to have the main artist work only on the most crucial details, while most of the work was left to his assistants. However, Michelangelo's ambition to produce a work that would be absolutely exceptional made it impossible for him to delegate. Michelangelo helped create his own legend, complaining of the enormous difficulties involved in the enterprise. In his sonnet On the Painting of the Sistine Chapel, he described all the discomforts involved in painting a ceiling, how much he hated the place, and how he despaired of being a painter at all.

In order to complete the task, Michelangelo had to design his own scaffolding and, after traditional plaster failed on him, had to use a new type of plaster, which was mixed for him by one of his assisstants. The new plaster formula subsequently entered Italian building tradition and is still used today.

After the death of Julius II in 1513, the two Medici popes, Leo X (1513-21) and Clement VII (1523-34) order Michelangelo to halt work on the tomb of their predecessor and commissioned him instead to decorate the Medici church of San Lorenzo in Florence. This project was aborted too, although Michelangelo finished some of the work for the Laurentian Library and the New Sacristy, or Medici Chapel, of San Lorenzo. The Medici Chapel fell just short of being completed: two of the Medici tombs intended for the Chapel were installed, the Tomb of Giuliano de' Medici and the Tomb of Lorenzo de' Medici; for the 3rd tomb, Michelangelo had almost concluded his last great Madonna (unfinished) when he left Florence for good in 1534.

It was during this period, while he was planning the tombs in the New Sacristy, that German Landknechts under Holy Roman Emperor Charles V sacked Rome (1527). Florentines used the resulting upheaval to overthrow the Medici and restore the republic, as a result of which, Florence was besieged shortly thereafter. Michelangelo used his expertise in engineering to help fortify the city, but despite this, Florence fell back into Medici hands in 1530. Michelangelo's alignment with the Florentine republicans naturally incurred the displeasure of Alessandro de Medici, but the latter was murdered in 1537 by Lorenzino, who was more sympathetic towards the artist. Michelangelo commemorated this event in his bust of Brutus.

In September 1534, Michelangelo settled down finally in Rome, where he was to remain for the rest of his life, despite flattering invitations from Cosimo I Medici to return to Florence. The new Pope, a Farnese who took the name of Paul III, confirmed the commission that Clement VII had already given him for a large fresco of The Last Judgment over the altar of the Sistine Chapel. Far from being an extension of the ceiling, this was an entirely different work and reflected many of the changes that the artist and his art had undergone. Over 20 years had passed between the two projects, full of political events and personal sorrows. The mood of The Last Judgment is somber; the naked Christ is not a figure of consolation, but one of vengeance and retribution, and even the Saved struggle painfully towards Salvation. The work was officially unveiled on 31 October 1541.

Michelangelo's last paintings were frescos in the Cappella Paolina just beside the Sistine Chapel, completed in 1550, when he was 75 years old: The Conversion of Paul and The Crucifixion of St. Peter.

In 1537-39, Michelangelo received a commission to re-design the Campidoglio, the top of Rome's Capitoline Hill, into a square. Although not completed until long after his death, the project was carried out essentially as he had designed it. In 1546, Michelangelo was commissioned to work on St. Peter's Basilica, which had been undergoing major renovation since 1506. While the overall design of the church remained that laid down by Donato Bramante, Michelangelo's predecessor at this task, Michelangelo was responsible for its dome and the exterior of the altar end of the building.

The two sculptural masterpieces of Michelangelo's later days were the extraordinary Late Pietas. The Rondanini Pieta in Milan, was literally one of the painter's last acts on this earth, as he was working on it just 6 days before his death. The artist's failing strength and haste can be seen in some of the atypically imprecise lines that form this sculpture.

Michelangelo died on the 18th of February 1564 at the age of 89 and was buried in Florence, in accordance with his wishes.

Michelangelo is, needless to say, one of the most highly-regarded artists of all time in the present day, and he was very well renowned in his own age. However, it was not always so, especially during the 17th century, when artists such as Raphael, Correggio and Titian were more in vogue. The modern-day cult of Michelangelo has its roots with the early Romantics in 19th Century Britain. In the 20th and 21st centuries, it was the unfinished, unresolved creations of the great master that evoked especially great interest, as aesthetic focus shifted from the finished piece of art, to the inextricable relationship between an artist's personality and his work.

Bibliography

Michelangelo. Poems. Correspondence. Opinions of Contemporaries. Moscow. Iskusstvo. 1983.

Michelangelo: Painting. by Luciano Bellosi. Thames and Hudson. 1984

Painting of Europe. XIII-XX centuries. Encyclopedic Dictionary. Moscow. Iskusstvo. 1999.

The Agony and the Ecstasy: A Biographical Novel of Michelangelo by Irving Stone. New American Library, 1996.

Michelangelo: The Complete Sculpture, Painting, Architecture by Michelangelo Buonarroti, William E. Wallace. Beaux Arts Editions, 1998.

Michelangelo: The Frescoes of the Sistine Chapel by Marcia B. Hall, Takashi Okamura (Photographer). Harry N Abrams, 2002.

Michelangelo by Diane Stanley. HarperCollins, 2000.

Michelangelo and the Pope's Ceiling by Ross King. Walker & Co, 2003.

Michelangelo: The Vatican Frescoes by Pierluigi De Vecchi, Gianluigi Colalucci. Abbeville Press, Inc., 1997.

- Pieta.

1499. Marble. St. Peter's, Vatican. Read Note.

- David.

1501-1504. Marble. Galleria dell'Accademia, Florence, Italy. Read Note.

- Pieta.

c.1550. Marble. Museo dell'Opera del Duomo, Florence, Italy. Read Note.

- The Battle Of Cascina, Copy After Michelangelo, Central Section Of The...

c.1542. Oil on panel. Holkham Hall, Norfolk, UK.

- The Sibyl Of Delphi.

1508-1512. Fresco. Sistine Chapel, Vatican. Read Note.

- Moses.

c.1513-1516. Marble. San Pietro in Vincoli, Rome, Italy. Read Note.

- Rebellious Slave.

c.1513-1516. Marble. The Louvre, Paris, France.

- Dying Slave.

c.1513-1516. Marble. The Louvre, Paris, France.

- The Tomb Of The Pope Julius Ii.

1542-1545. Marble. San Pietro in Vincoli, Rome, Italy.

- Victory.

c.1520-1525. Marble. Palazzo Vecchio, Rome, Florence, Italy.

- Crouching Boy.

c.1524. Marble. The hermitage, St. Petersburg, Russia.

- The Interior Of The Sistine Chapel Showing The Ceiling Fresco.

Sistine Chapel, Vatican. Read Note.

- The Last Judgment. Detail.

1534-1541. Fresco. Sistine Chapel, Vatican. Read Note.