Georges Braque Biography

Georges Braque (1882-1963) was a notable French artist, considered, together with Pablo Picasso, to be the founding father of Cubism, one of the definitive art movements of the 20th Century. He is probably one of the best known French painters today.

Georges Braque was born on May 13, 1882, in the village of Argenteuil-sur-Seine, the village made famous by Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Edouard Manet and, most of all, Claude Monet. His family soon moved away, in search of work, and finally settled in the northern port town of Le Havre, where Georges' father started a painting and decorating business. Braque elder was an amateur artist himself, and fully supported his son when Georges began to attend evening class at the Le Havre Ecole des Beaux-Arts.

Braque did not immediately settle on a career of painting, and there was at least some pressure from his parents to carry on the family business so, in 1899, he became apprenticed to a local painter-decorator named Roney. Soon after, the young man moved to Paris, where he gained his craftsman's diploma in 1901. Ready-made decorative panelling, so ubiquitous these days, was, of course, unavailable at the turn of the century, and so a painter-decorator was a skilled artisan employing some unusual techniques: for example, he had to be able to imitate a variety of natural textures, such as wood or marble, using his brush. Georges Braque's professional training would contribute to the later development of the theory and practice of Cubism.

In 1902, Braque went through a period of mandatory military service, during which he decided that he was interested in pursuing the career of a professional artist. He enrolled at the Academie Humbert, where he made the acquaintance of Francis Picabia, Raoul Dufy and Othon Friesz. Both the latter two also hailed from Le Havre and had, in fact, attended the Ecole des Beaux-Arts there, albeit slightly before Braque's time. In Paris, the young painter was exposed to a variety of influences, ranging from ancient Greek and Roman art, to the Neo-Classicists, to the Impressionists, Van Gogh and Gauguin. His work of the time, much of it later destroyed by the artist, clearly reflects the influences he was exposed to.

After two years at the Academie Humbert, Georges Braque rented his own studio in the Montmartre district -- beloved of poor young painters -- and set out on his own. Works from this time period, such as Boats (1901-5) and Ship in Harbor, Le Havre (1905), demonstrate the influence of Cezanne, Van Gogh and, to some degree, the Pointillists.

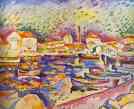

In 1905, after returning from a summer spent at home in Normandy, the artist was greatly impressed by the debut of the Fauves at the Salon d'Automne. He soon fell in with the group gathered around Henri Matisse and Andre Derain, starting on a period of experimentation that would last the next few years. In March 1906, Braque had his work exhibited for the first time, contributing seven paintings to the Salon des Independents. That winter, he stayed in the Mediterranean fishing town of L'Estaque, near Marseilles, and it was here that he achieved his peak as a Fauve, with such paintings as Le Mas (1906), At L'Estaque (1906) and La Ciotat (1907). Already, however, his art was displaying a growing fascination with geometric patterns and solid, defined forms that was out of step with the canon preached by Matisse. Braque was ready to move on.

Paul Cezanne had died in 1906, and there was a large retrospective of his work the following year, which attracted the attention of many avant-garde artists of the time, including Braque and his soon-to-be colleague Pablo Picasso. The former reacted by painting View from the Hotel Mistral, L'Estaque (1907), in which he abandoned the Fauvist tenets of color and moved towards a simplified Cezannian geometry. The latter reacted by painting Les Demoiselles D'Avignon (1907), one of the most iconic works of the 20th Century.

The two founders of Cubism met through Guillaume Apollinaire, who had seen Braque's work at the gallery of Daniel Kahnweiler, a German art dealer who had moved to Paris in pursuit of new movements in art. At Picasso's studio, situated less than two blocks from his own, Braque was confronted with the Demoiselles D'Avignon, allegedly reacting with shock and revulsion. Soon afterwards, however, the artist painted the Nude (1907-08), clearly inspired by Picasso's work. Braque's move towards Cubism had begun.

After painting the Nude, more as a tribute to Picasso than anything else, Braque returned to his practiced field of landscape, experimenting with the new Cubist ideas. See: Houses at L'Estaque (1908), Trees (1908) and Landscape at L'Estaque (1908). Rather than striving for any sort of representational approach, the painter did his best to get rid of the appearance of distance. The landscapes are executed from a high angle that eliminates the line of the horizon, and objects are maximally flattened, almost acquiring the appearance of theater scenery.

It was, perhaps, quite logical that the next step for both Braque and Picasso was to be still-life. In a movement that aimed to do away with the traditional tenets of perspective in favor of art that emphasized a multiple-view approach, the still-life was the most natural subject. One of Braque's first works in this genre in the Still-Life with Fruit-dish and Plate (1908).

In 1908, the painter submitted six works to the Salon d'Automne, but though the jury included multiple avant-garde artists, Matisse among them, they proved unresponsive to Braque's innovations, and rejected his paintings out of hand. It was to be many years before the artist again submitted his work to the Salon. In the meanwhile, Braque's dealer Daniel Kahnweiler arranged an exhibition of the painter's work at his gallery. This was the first Cubist exhibition. The critic Louis Vauxcelles, who had coined the term "Fauvism" three years earlier, was in attendance, and dismissed the new art movement as a reduction of "everything, landscapes and figures and houses, to nothing more than geometrical patterns, to cubes." Thus, he became responsible for christening one of the most influential art movements of the 20th Century: Cubism.

Braque spent the summer of 1909 at La Roche-Guyon, on the Seine. His return to Paris that Autumn marked the beginning of his collaboration with Picasso, which would last the next 5 years. The two painters sought to further their effort at getting rid of perspective in art, focussing instead on shape and volume. The works of this period are characterized by bland, neutral colors, as Braque believed bright colors would detract from the idea they were trying to get across. He himself described their approach to painting as an "image seen through broken glass -- the shapes distorted, but not broken." Iconic works of this period include Woman with a Mandolin (1910), the Gueridon (1910-1911), Woman Reading (1911). Juan Gris, the young Spanish painter who would become the third member of the Cubist trio, called this period in Braque's and Picasso's art "Analytical Cubism".

In 1910, Braque started a relationship with Marcelle Lapre, a professional model who had been introduced to him by Picasso (she is listed in some literature as Marcelle Varvonne, her father's surname; however, her parents were never married). The couple wed in 1912. They spent that summer at a house they had rented in the small town of Sorgues in southeastern France. It was here that the next stage of his art -- Synthetic Cubism -- was born. Braque, seeking to re-introduce color and texture to his compositions, tried to do this by pasting pieces of wallpaper, fabric and simulated wood panelling onto his drawings. This was the birth of the papier colle technique that he and Picasso were to popularize. It is doubtful that Braque would have been able to make this leap without his training as a house decorator, early in his life. Thus were born such works as Aria de Bach (1913), Still-Life with Playing Cards (1913) and Music (1914). They would be the last products of his association with Picasso.

On August 1, 1914, France declared a full-scale mobilization of its armed forces in response to Germany's and Austria-Hungary's declaration of war against Russia. It was the beginning of World War I. Georges Braque had just turned 32 and was a member of the reserve, so he was among the first to receive his mobilization papers. Picasso and Juan Gris, both Spaniards and so exempt from military service, saw hin off at the station. Weeks later, Braque was in the trenches as a sergeant of the infantry.

The artist served with distinction. He was mentioned twice in despatches, awarded the Croix de Guerre and soon promoted to second lieutenant. On May 11, 1915, just two days shy of his 33rd birthday, Braque was hit in the head by a piece of shrapnel and almost killed. The painter spent the next year and a half in various military hospitals, during which time he was recommended for and received the Legion d'Honneur, France's highest decoration. In January 1917, deemed unfit for further military service he was discharged and returned to Paris, where he was warmly welcomed back by his friends, including Juan Gris and the sculptor Henri Laurens.

Braque returned to painting in the summer of 1917, after a hiatus of nearly 3 years. There was little reflection of the war in the subject matter of his paintings: the Guitar (1917), the Musician (1917-1918), the Black Gueridon (1919). The works become noticeably darker in tone. Though the techniques are very similar to his pre-war paintings, the artist now often makes use of a dark background, somewhat akin to the older Georgian painter Niko Pirosmani and his black oilcloths.

Braque's stylistic break with Picasso (who at the time was going through his Classicist period) marked also his rise to prominence as an artist in his own right. Overshadowed by Picasso's sociable and flamboyant figure in the pre-War years, Braque had been regarded, rather unfairly, as the junior member of their partnership. This now changed. In 1919, the artist had a one-man exhibtion at the gallery of his dealer Leonce Rosenberg, his first major appearance before the public since the pre-war years, and experienced great success, selling his works at relatively high prices for the first time. In 1922, the Salon d'Automne recognized Georges Braque's anniversary by devoting an entire room to his paintings. All of them sold well, though Braque had a violent argument with Rosenberg, who had put up a number of Braque's old Cubist works at far below their going price at the time, which ended with the dealer being struck violently to the ground.

In 1924, after a successful one-man exhibition with his new dealer Paul Rosenberg, the painter purchased a house in Paris's well-to-do 14th arrondissement. This was to remain his city home until he died.

Through the 20s, the painter's works, after verging on the abstract, grew more representative and lyrical. As Picasso was discovering simultaneously, Cubism in its purest form had its creative limitations. As soon as an artist arrived at his pinnacle in the new field, it became neccessary to move beyond it. Braque's repertoire of these years focused on two principle themes: the nude, for example, Canephorus (1922-23) and Reclining Nude (1925), and the still-life, such as Bottle, Glass and Fruit (1924) and Still-Life with Fruit (1926). In both of these he was following very much in the French tradition of the cabinet-painting, dating back to Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot and Simeon Chardin.

It was not in Braque's nature to remain long in one place, artistically speaking, and towards the end of the 1920s another transformation took place in his artwork, with his palette lightening and the Gueridon once again rising to a place of prominence in his work.

In 1929, the painter spent the summer on the Normandy coast, where he had been raised, but which he had not returned to since 1905. Two years later, in 1931, Braque had himself built a house at Varengeville, near Dieppe. It was here that he would spend most of the rest of his life. As countless painters before him had discovered, the Norman coastline invited art of the landscape genre, and to this Braque gradually returned with paintings such as Boats on the Beach, Dieppe (1929). For the first time in over 20 years, the sky appears again in his paintings. Simultaneously, the painter was developing an interest in line that led to his invention of the platre grave: on a plaster surface painted in a dark color, usually black, he would carve lines, much in the fashion of pre-Classical Greek intaglio. Examples include the Clay Pipe (1931) and Nereid (1931-32). It was during that period that Braque first tried his hand at lithography, which would become his most prolific medium through his latter years.

The year 1932 was also important because Braque, now fifty, had his first major retrospective exhibition, which took place in Basle's Museum of Art.

Braque's output of the 30s possessed the confidence and exuberance of an artist in his prime. No longer content with depicting merely the real, he introduced stylistic elements that were purely ornamental, and expressed emotional and metaphysical aspects of a piece, rather than purely visual ones. Vivid examples include the Yellow Tablecloth (1935), Still-Life with Fruit-Dish (1936), the Duet (1937), Vanitas I (1938).

In 1940, when the German tanks rolled across the Belgian border, Braque and his wife were staying in Varengeville. Along with countless other French civilians, they fled southeast, first staying in the Limousin region, and then moving on to the Pyrenees, where in 1911, Braque had spent a summer with Picasso, advancing the Cubist theory. However, once the situation in France stabilized, with the Germans occupying the north, and the Vichy French State controlling the south, the painter preferred to return to Paris, where he remained until the end of the war.

Just like the First World War, the Second World War had little affect on the subject matter of Braque's works, which continued much in the same vein as the later 1930s. There were many more interiors than previously (The Black Fish, 1942; Interior: the Grey Table, 1942; Billiard-Table I, 1944) and, of course, the Normandy landscapes disappeared wholly. The artist also took up sculpture and colored lithography during the war, which, viewing these media as "less serious" than his oil canvases, served as a means for him to take a break from painting.

The war passed by without accident, but in the three years that followed it, Braque painted little, recovering from a serious illness he contracted in 1945, and then from another he contracted in 1947. Almost all the output from this period consists of lithographs, which were less physically demanding than oils. Just as during his convalescence from his head-wound in World War I, the painter used the time to meditate on his art and the direction it was going, as well as write a short autobiographical treatise entitled Le Cahier de Georges Braque (The Notebook of Georges Braque, published 1948). That year, Braque was invited to represent France at the Venice Biennale, the first Biennale since the outbreak of the war, where he won first place. Two years earlier, in 1946, a number of the painter's war-time works were exhibited at the Tate Gallery in London, his first exhibition in the United Kingdom.

In 1948, fully recovered and refreshed, Braque embarked on the series of paintings that is considered by some to be his masterpiece -- the Studio series. Although the series consisted of a total 8 paintings (Studio I, II, III, IV, V, VI, VIII and IX), they occupied most of the next decade of the artist's life, culminating with Studio IX, which was completed in 1956. As the name implies, the subject of these works was the artist's own workspace. Redolent with paints and other artistic supplies, the fruit, glassware, platforms and drapery that were used in Braque's still-lifes, as well as easels with unfinished works -- the painter would sometimes have dozens of these at the same time -- the studio was the perfect subject for this next stage in Braque's artistic evolution. In these works, the purpose of depicting reality becomes wholly secondary. The canvases are a juxtaposition of real objects and images that exist only in the painter's imagination, and the question of what is real and what fancied is left purposely ambiguous.

The Studio series, together with some major decorative commissions, occupied the painter through most of the 50s. Another serious illness in the winter of 1953-54 prevented him from undertaking any more ambitiious projects. However, he did manage to produce two final figure compositions: the Night (1951) and Ajax (1955). After 1956, the dominant theme in Braque's work became the flying bird, which he saw as a personal symbol of his art, and it is one of these that he chose in 1958, when asked for a painting to represent himself at the World Fair. The work he displayed was the then-unfinished Bird Returning to its Nest (1959).

The artist died on August 31, 1963, in his Paris home. He was buried at Sainte-Marguerite-sur-Mer, in Normandy. Some of the last work of Georges Braque -- Georges Braque the Fauve, Georges Braque the Cubist, Georges Braque the Expressionist -- hearks back to the turn of the Century, as if the artist sought to bring his life's work full circle. Paintings such as The Plough (1959-60), The Belgian Plough (192), The Weeding Machine (1961-63) are reminiscent, more than anything, of the Post-Impressionists Cezanne, Gauguin, Van Gogh, who had been the original inspiration for the Modernists to whom Braque belonged.

Bibliography

Georges Braque by Georges Braque, Jean Leymarie. Prestel Publishing, 1988.

Georges Braque. A Life. by Alex Danchev. Arcade Publishing, New York. 2005.

Braque: The Late Works by John Golding, Sophie Bowness, Isabelle Monod-Fontaine. Yale University Press, 1997.

Georges Braque. Text by Raymond Cogniat. The Library of Great Painters. Harry N. Abrams, Inc., Publishers, NY. 1980

Braque. by Francis Ponge, Pierre Descargues, Andre Malraux. Harry N. Abrams, inc./Publishers/New York

Picasso and Braque. Pioneering Cubism. The Museum of Modern Art, NY. 1989.

The Essential Cubism 1907-1920. by Douglas Cooper and Gary Tinterow. George Braziller, Inc. New York in association with Tate Gallery, London. 1983.

Georges Braque. by Karen Wilkin. Abbeville Press. NY. 1991 (last scans from here)

Braque by Serge Fauchereau. Rizzoli International Publications, Inc.. New York 1987 (last scans from here)

Cubism. by Philip Cooper. Phaidon Press ltd. 1995.

Cubists by Jeremy Wallis. Heinemann Library, Chicago, Illinois, 2003

- L'Estaque.

1906. Oil on canvas. Private collection.

- Landscape At La Ciodat.

1907. Oil on canvas. 71.7 x 59.4 cm. The Museum of Modern Arts, New York, NY, USA.

- View From The Hotel Mistral, L'Estaque.

1907. Oil on canvas. 81 cm x 61 cm. Private collection.

- The Musician.

1917-18. Oil on canvas.220.8 x 113 cm. Kunstmuseum Basel, Basel, Switzerland.

- Big Nude.

1907-8. Oil on canvas. 139.5 x 101.8 cm. Private collection.

- Houses At L'Estaque.

1908. Oil on canvas. 73 x 60 cm. Kunstmuseum, Berne, Switzerland.

- Big Tress At L'Estaque.

1908. Oil on canvas. 79 x 60 cm. Private collection.

- Landscape.

1908. Oil on canvas. 81 x 65 cm. Kunstmuseum Basel, Basel, Switzerland.

- Plate And Fruit Dish.

Autumn 1908. Oil on canvas. 46 x 55 cm. Private collection.

- Woman With A Mandolin.

1910. Oil on canvas. oval 92 x 73 cm. Bayerische Staatsgemaldesammlungen, Munich, Germany.

- Pedestal Table.

1911. Oil on canvas. 116.5 x 81.5 cm. Musée National d'Art Moderne, Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris, France.

- Woman Reading.

1911. Oil on canvas. 130 x 81 cm. Private collection.

- Still Life With Playing Cards.

1913. Oil on canvas. 80 x 59 cm. Musée National d'Art Moderne, Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris, France.

- Still-Life With A Violin, Glass And Pipe On Table (Also Known As Music).

Spring 1914. Oil, gesso and sawdust on canvas. 91.5 x 59.7 cm. The Phillips Collection, Washington, DC, USA.

- The Black Guéridon.

1919. Oil on canvas. 75 x 129.8 cm. Musée National d'Art Moderne, Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris, France.

- Canephorae.

1922. Oil and sand on canvas. 181 x 73 cm. Musée National d'Art Moderne, Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris, France.

- Barques Sur La Place.

1929 (?). Oil on canvas. Private collection.

- The Yellow Napkin.

1935. Oil on canvas. Private collection.

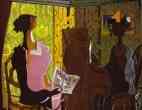

- The Duet / Le Duo.

1937. Oil on canvas. 129.8 x 160 cm. Musée National d'Art Moderne, Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris, France.

- Vanitas.

1939. Oil on canvas. Private collection.

- The Black Fish.

1942. Oil on canvas. 33 x 54.8 cm. Musée National d'Art Moderne, Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris, France.