Piet Mondrian Biography

Piet Mondrian (1872-1944) was a Dutch Abstract painter of the first half of the 20th Century. A contemporary and disciple of the famous cubists Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque, Mondrian challenged the definition of art itself, working with simple lines, right angles, correct geometric figures and pure, primary colors. His work attained a level of abstraction far beyond that of even his most progressive colleagues.

The painter was born Pieter Cornelis Mondriaan, in 1872, in Amersfoort, a small town in central Holland. Though once prosperous, by the end of the 19th Century, most of the population lived in relative property, and the town was a bastion of religious fanaticism. Mondrian's father, head teacher at the local primary school was a devout Protestant, and often neglected his family in favor of service to the church and charity. Mondrian's mother was often sick, and it fell to Mondrian's elder sister, Johanna Christina to take charge of her four brothers, of whom Pieter, the eldest, was only two years younger than she.

His miserable childhood in Amersfoort and unstable life at home made the future artist introspective, cynical and bitter. His father taught him how to draw at a young age and art became for Mondrian a way to escape day-to-day reality and immerse himself in the world of his imagination.

In 1892, the painter expressed his wish to receive a formal education in art, and his father helped him move to Amsterdam and enroll in the State Academy of Art (Rijksakademie voor Beeldende Kunst), through his religious acquaintances.

The following years were a particularly difficult time for the artist. The Netherlands were going through a period of social upheaval, and the painting profession paid poorly. At around this time, Mondrian joined the radical Protestant Gereformeerde Kerk ("Reformed Church"), which espoused the view that the world was going through the end times and sought to prepare its members for the coming societal collapse. The idea of an approaching change in the structure of society appealed to the artist's desire to escape his poor circumstances.

Several times, Mondrian was forced to interrupt his education. He spent the entirety of 1897 with his brothers in the countryside. Falling ill with pneumonia in the autumn of 1898, he had to spend most of the following year in his parents' home.

During these years, Mondrian painted prolifically, producing illustrations, most of them religious, some portraits and a large amount of watercolor landscapes, depicting rural scenes. Examples of his works of the period include: Girl Writing (1892-95), Landscape with Ditch (1895), View of Winterswijk (1898-99), Self-Portrait (1900). Although little innovation is immediately apparent in these works, Mondrian had already come to understand that the future of painting did not lie in realism. Many of the works -- even the landscapes -- were painted in his studio, not en plein air, and sought to capture mood rather than detail. There is a certain resemblance to the paintings of the Post-Impressionists, like Paul Cezanne and Vincent Van Gogh, and the early Art Nouveau artists, like Gustav Klimt.

In 1898 and again in 1901, Mondrian entered the contest for the Prix de Rome, the most prestigious art award in the Netherlands, both times unsuccessfully. The judges, all of whom were leading art critics, were very much proponents of the academic tradition and criticized Mondrian's offerings scathingly, and the artist realized that recognition would only come through the acceptance of the public.

In 1904, social unrest in the Netherlands turned violent, and Mondrian, who had been associated with several extremist political parties, fled to the countryside. Isolating himself here, he began a process of reinventing his art, his public image and himself.

The painter's first step was to begin catering to the tastes of the public, instead of focusing primarily on his own artistic interests. He produced many "typical" Dutch landscapes, depicting windmills and conventional pastoral scenes. Paintings of flowers, highly detailed and posed against uniform backgrounds are also very typical of this period (see Chrysanthemum, 1908, and Amaryllis, 1910). This work, which met with greater demand than modern art, at last allowed Mondrian to improve his financial circumstances to a more comfortable level.

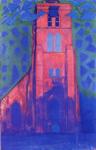

For himself, however, he continued experimenting with color and abstraction, emulating in many ways the ideas of the Fauves in Paris. The nocturnal landscape was a favorite theme during this period, for example Summer Night (1906-07), Trees by the Gein at Moonrise (1907-08) and Woods near Oele (1908). Towards 1910, the colors and compositions of his paintings simplified. Works such as Windmill in Sunlight (1908), Dune Landscape (1910-11), Church near Domburg (1910-11) and the Red Mill (1910-11) use nothing but primary colors.

In 1911, Mondrian attended the exhibition of Georges Braque. The work of the French Cubist impressed the Dutch painter greatly, as it paralleled much of what he had been experimenting with on his own, and Mondrian resolved to visit Paris, fascinated by the artistic innovations being introduced there.

However, arriving there in the winter of the same year, the artist made no attempt to contact any of the French modernists. Though he followed the development of their art and theory, he had no wish to enter their circles. Instead, Mondrian rented a small studio and went on with his experimentation in private. It is possible that the artist, with his provincial, lower-class origins felt self-conscious about approaching the crème de la crème of contemporary French art.

There is evidence that the artist had been growing disillusioned with the church and religion in general prior to his arrival in Paris. In any case, this was when he broke with it formally. At the same time, he changed his name to the more French-sounding Piet Mondrian, removing the double "aa" from his surname and shortening his first name to just "Piet."

During this period, the artist adopted the bold, black Cubist grid as the foundation of his compositions. Unlike Braque and Picasso, however, who worked mostly with people and still-lifes, Mondrian applied the Cubist ideas to landscapes and cityscapes. Works of this period in the painter's life include Apple Tree in Flower (1912), Trees in Blossom (1912), Tableau III (1914) and Composition No. 10: Pier and Ocean (1915).

In 1914, just before the outbreak of World War I, Mondrian traveled back to the Netherlands to visit his father, who had fallen seriously ill. The beginning of the war forced him to remain in Holland for the next 5 years.

Returning from Paris a mature and sophisticated painter, Mondrian for the first time took an interest in Amsterdam's high society. Appearing at social functions, he managed to win over the critics and secured the patronage of the wealthy Kroller-Muller family, through the art historian H.P. Bremmer. The Kroller-Mullers paid Mondrian an annual stipend and purchased numerous of his works for their collection.

In 1916, Mondrian moved to Laren, which had been an artists' colony since the early 19th Century and there, he began to gather around himself a circle of modern Dutch painters, designers and architects. One of Mondrian's most important new acquaintances turned out to be Theo van Doesburg, a fellow abstract painter, writer and designer. With his knowledge of art history and philosophy, van Doesburg inspired Mondrian to focus on the theory behind his works. In 1917, van Doesburg founded the art magazine De Stijl (Dutch for "Style") and Mondrian's essays would frequently appear in it, along with the best modern Dutch artwork.

Probably as a consequence of his difficult childhood, Mondrian had a tendency to distance himself from other people and, as a consequence, had few lasting relationships. However, during this period, the painter made an attempt to settle down. In 1914, he became engaged to Greet Heybroek, and the two married soon afterwards. The marriage lasted only three years and would be Mondrian's first and only attempt at family life.

His development as an artist did not stand still during this time. Although his artistic output dropped sharply, his canvasses became more deliberately abstract than ever, moreso, perhaps, than his later works. All attempts at depicting a specific subject disappeared, the paintings becoming grid-like arrangements of colored blocks and rectangles. Notable works include Composition (1916), Composition with Color Planes No.3 (1917), Composition Chequerboard: Dark Colors (1919) and Composition: Light Color Planes with Grey Contours (1919).

In 1918, Mondrian discovered the "lozenge": a square, tilted 45 degrees that became a key motif of his work. The painter was inspired by a stained glass window created by Theo van Doesburg and, indeed, his works have the appearance of stained glass, see Lozenge with Grey Lines (1918) and Composition: Light Color Planes with Grey Lines (1919).

In 1919, with the First World War safely over, Mondrian returned to Paris in order to see his studio -- which he had never intended to abandon for such an extended period of time -- and catch up with the latest developments in modern art. The artist was in for a shock.

Picasso's and Braque's return to more representational painting disappointed Mondrian severely. The painter, who just a few years earlier felt himself to be, at best, the French Cubists' younger brother, had by now far surpassed them in terms of the modernist ideals. This sudden success frightened him. In addition, Mondrian's uncompromising struggle for new heights of abstraction had alienated his clients and, feeling that he no longer had anything to paint or anyone to paint for, the artist suffered a breakdown, even threatening to abandon painting forever.

In the end, however, he did not. Deciding to remain in Paris, Mondrian set about reinventing himself and his art anew. At the beginning of his career as a painter, he had earned money by painting simple floral compositions and to these he now returned. Simultaneously, he developed a new style of abstract painting, replacing his cluttered canvasses of before with works of a new-found simplicity. His color palette was pared down to just the pure, undiluted, primary colors and the number of elements decreased from dozens to not more than a handful per painting. See Composition (1921), Tableau I (1921) and Composition with Red, Yellow, Blue and Black (1921). Mondrian took great pains over each work of art, painting and re-painting the geometric shapes multiple times until he achieved the exact effect he wanted.

He also sought to apply his abstract ideas to other media, and started by decorating his Paris studio completely in his new style, with bold black lines and rectangles of red, yellow and blue amid large fields of white. Indeed, the painter completely re-made his public image. He no longer allowed photographers to take pictures of him as he worked. Instead, he always appeared for photographs immaculate, in formal dress, in the context of his studio, which now doubled up as a showroom of his art and ideas.

This artistic revival coincided with a tragic period in the painter's career. In 1921, his father, a man of great influence in Mondrian's life, died.

In the mid-1920s, Mondrian tried his hand at the design of interiors and stage sets. However, where the painter's artwork was at the cutting edge of the avant-garde, his design work was hopelessly conservative and traditional, even if it subscribed to his color theory, and none of the designs -- except that of his studio -- were ever realized. Mondrian's failure as a designer caused him to fall out with his friend Theo van Doesburg, who was very successful in this field. According to the popular version of events, the two painters had a clash over the position of lines in a painting, but this is probably not true.

As a consequence of the argument with Doesburg, the artist stopped making contributions to De Stijl and broke contact with the Dutch abstractionists. Instead, he exhibited his works in the Abstract Gallery of the Russian artist El Lissitzky, alongside the works of such painters as Kazemir Malevich and Wassily Kandinsky, who he felt were more in tune with his understanding of contemporary art.

Meanwhile, Mondrian took abstraction to an even greater extreme, with paintings consisting of nothing but a few lines, such as Composition with Two Lines (1931), Composition II with Black Lines (1930) and Composition with Yellow Lines (1933). The Composition with Two Lines was originally painted for the Hilversum Town Hall. The citizens of Hilversum, however, were unimpressed with the work and sold it to the Stedelijk Museum (City Museum) of Amsterdam.

In 1932, a major retrospective exhibition of Mondrian's work was held at the Stedelijk Museum, in honor of the artist's 60th birthday.

It was around this time that the painter began to be fascinated with the idea of the line and dismantling the very definition of painting. Drawing and draughtsmanship -- exemplified in the line --, he argued, had always lain at the heart of painting, from the Renaissance to the Impressionists to the Modernists, and no one had ever thought to challenge that.

The artist started out by playing with the bold black lines he used in his own art, varying them in thickness, length, span and regularity. The evolution can be seen clearly in the works of this period, such as Composition with Red and Blue (1936), Composition with Blue (1937) and Composition (1939). Finally, with his Composition with Red, Yellow and Blue (1939-1942), he made a breakthrough, making two of the lines in color and thus blurring the definition of drawing, and the role of draughtmanship.

In 1938, as the political situation in Europe began to grow tense, Mondrian abandoned the continent for London, where he stayed with the British artists Ben Nicholson and Barbara Hepworth. In 1940, with France fallen to Nazi Germany, and England suffering daily air raids, the artist took a ship to New York, despite the risk of U-boats. He held a number of exhibitions in the United States together with other European Abstract artists who had fled there to escape the war and the oppressive Nazi regime, which viewed modern art as an aberration.

Through all this, Mondrian advanced with his theory. As during all his periods of experimentation -- and probably as a consequence of frequent travel -- his output dropped, but each piece was executed with a lot of thought and deliberation. New York, New York (1941-42) features a larger number of colored lines, as the artist sought to break up the established structure of his work. By New York City I (1942), black lines are completely gone. In Broadway Boogie-Woogie (1942-43), the colored lines are broken up with patches, completely defying the definition of anything that could be called drawing.

Mondrian's last painting, Victory Boogie-Woogie, which he began in 1943, sadly remained unfinished at the time of the artist's death on February 1, 1944, from pneumonia. The painter's sole heir was the young artist Harry Holtzman, whom he had befriended during the last decade of his life, and in favor of whom Mondrian disinherited his younger

Bibliography

Mondrian: On the Humanity of Abstract Painting by Meyer Schapiro. George Braziller, 1995.

Mondrian by John Milner. Phaidon Press, 1995.

Complete Mondrian by Marty Bax. Lund Humphries Publishers, 2002.

Mondrian: The Transatlantic Paintings by Harry Cooper, Ron Spronk. Huam, 2001

Mondrian: The Art of Destruction by Carel Blotkamp. Reaktion Books, 2004.

Piet Mondrian by Joop M. Joosten. Harry N. Abrams, 1996.

- Girl Writing. / Schrijvend Meisje.

c.1892-95. Black chalk on paper. 57 x 44.5 cm. Gemeentemuseum, the Hague, Netherlands.

- Landscape With Ditch. / Landschap Met Sloot.

c.1895. Watercolor. 49 x 66 cm. Gemeentemuseum, the Hague, Netherlands.

- View Of Winterswijk.

1898-99. Watercolor. 52 x 63.5 cm. Private collection.

- Self-Portrai / Zelfportret.

c.1900. Oil on canvas, mounted on stone. 50.4 x 39.7 cm. The Phillips Collection, Washington, DC, USA.

- Chrysanthemum / Chrysant.

1908-10. Charcoal on paper. 36.4 x 24.8 cm. Private collection.

- Amaryllis.

1910. Watercolor over pen. 49.2 x 31.5 cm. Private collection.

- Summer Night / Somernacht.

1906/07. Oil on canvas. 71 x 110.5 cm. Gemeentemuseum, the Hague, Netherlands.

- Trees By The Gein At Moonrise. / Bomen Aan Het Gein Bij Opkomende Maan.

1907-08. Oil on canvas. 79 x 92.5 cm. Gemeentemuseum, the Hague, Netherlands.

- Woods Near Oele. / Bos Bij Oele.

1908. Oil on canvas. 128 x 158 cm. Gemeentemuseum, the Hague, Netherlands.

- Windmill In Sunlight / Molen Bij Zonlicht.

1908. Oil on canvas. 114 x 87 cm. Gemeentemuseum, the Hague, Netherlands.

- Dune Landscape./ Duinlandschap.

1910-11. Oil on canvas. 141 x 239. Gemeentemuseum, the Hague, Netherlands.

- Church Near Domburg ./ Kerk Te Domburg.

1910/11. Oil on canvas. 114 x 75 cm. Gemeentemuseum, the Hague, Netherlands.

- The Red Mill. / De Rode Molen.

Oil on canvas. 150 x 86 cm. Gemeentemuseum, the Hague, Netherlands.

- Apple Tree In Flower. / Bloeiende Appelboom.

Oil on canvas. 78 x 106 cm. Gemeentemuseum, the Hague, Netherlands.

- Trees In Blossom. / Bloeiende Bomen.

1912. Oil on canvas.65 x 75 cm. The Judith Rothschild Foundation, New York, NY, USA.

- Tableau Iii.

Oil on canvas. 140 x 101 cm. Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam, Netherlands.

- Composition No.10 (Pier And Ocean) / Compositie Nr.10 (Pier En Oceaan).

Oil on canvas. 85 x 108 cm. Rijksmuseum Kröller-Müller, Otterlo, the Netherlands.

- Composition / Compositie.

1916. Oil on canvas. 119 x 75.1 cm. The Solomon R. Guggebheim Museum, New York, NY, USA.