Frida Kahlo Biography

Frida Kahlo was born on July 6, 1907, the third of four daughters of Wilhelm Kahlo, a German Jew of Hungarian descent, and Matilde Calderon de Kahlo, a mestizo Mexican. The family lived in a house ("The Blue House") that the parents had built themselves in 1904, in Coyoacan, a suburb of Mexico City.

Frida’s maternal grandfather had been a photographer and had taught her father the craft. Wilhelm, who changed his name to Guillermo when he became a Mexican citizen, set himself up in business and rose to relative prosperity, receiving commissions from the Mexican government. However, the Mexican Revolution, which started in 1910 and would continue for several decades, brought an end to this work, and as a result, Kahlo’s childhood was spent in relative poverty, forcing her to start working at an early age.

In 1913, at the age of 6, Frida contracted polio, which left her right foot crippled and earned her the cruel nickname “Peg-leg Frida.” Kahlo was very sensitive about this deformity, and this would lead her to wear, at first, trousers and, later, long exotic skirts that would become one of her trademarks.

Unlike many artists, Frida did not start painting at an early age. Although her father dabbled in painting as a hobby, his daughter was not particularly interested in art as a career and did not pursue it seriously.

Frida Kahlo received her primary education at the Colegio Aleman, Mexico City's German school. In 1922, she graduated and became a student at the Escuela Nacional Prepatoria (National Preparatory School), rated the best preparatory college in Mexico. Kahlo was one among only 35 female students out of a total of some 2,000. She studied the natural sciences, with the eventual aim of becoming a medical doctor.

It was at the Escuela that she first became acquainted with the ideas of socialism and national-socialism. Kahlo joined a group called the "Cachuchas", so named after the caps they wore. Several members of the group would later become prominent cultural and political figures.

The event that would transform her life and launch her artistic career took place in the September of 1925. Returning home from school with her boyfriend, Alejandro Gomez Arias, the pair was caught in a terrible accident. The bus that they were riding on collided with a tram, killing several people. Kahlo suffered severe injuries and was confined to bed for many months.

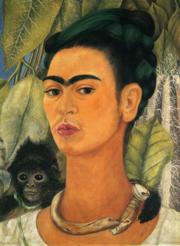

It was during this period that she took up the paintbrush, to distract herself from the pain and boredom of her condition. Her parents provided her with a mirror, so that she could serve as her own model, and this was how Kahlo began painting the self-portraits that would dominate her repertoire.

Some of her early works include the Self-Portrait in a Velvet Dress (1926), Portrait of Miguel N. Lira (1927), Portrait of Alicia Galant (1927) and Portrait of My Sister Christina (1928). With their muted colors and largely one-tone backgrounds, these works exhibit the prevailing European influence on Mexican art. This, however, was soon to change.

The ongoing Mexican Revolution was accompanied by a cultural reform, which sought to raise the status of indigenous Indian culture to the same level as the Spanish culture imported from Europe. The evolution of the dry, academic European style into the vibrant, colorful Mexicanist style can easily be seen in Kahlo's work.

By 1928, the painter had recovered sufficiently to lead a mostly normal life and she resumed contact with her old friends, many of whom had by now graduated the Escuela and were at university. It was through them that she got to know Diego Rivera, an established and esteemed painter, twenty one years her elder. The two of them had met before, when Rivera was painting a mural at the Escuela's amphitheatre, in 1922, but had not had any contact since. When Kahlo showed Rivera her work, he was greatly enthused and encouraged her to pursue painting professionally. The two would marry on August 21, 1929.

A year earlier, in 1928, Kahlo had joined the Mexican Communist Party.

By the end of the 1920s, the political climate in Mexico was starting to change. The president Plutarco Elias Calles, who ruled formally from 1924 to 1928, and then held on to power secretly until 1934, cut funding for large mural paintings, leaving Rivera, who specialized in murals, in dire straits, financially. In addition, Calles took repressive measures against political opponents, the Mexican Communist Party among them. Although Rivera had left the party in the 1920s, he was viewed as a sympathizer.

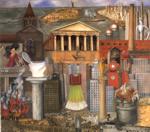

It was for these two reasons that, in 1930, Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo moved to the United States. There, Rivera hoped to find a better market for his art, as well as safety from possible persecution. The couple would stay in the country for 4 years, traveling and staying in San Francisco, New York City and Detroit, as Rivera received commissions for murals.

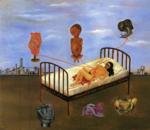

In 1930, Kahlo became pregnant. Unfortunately, the injuries that she had suffered in the 1925 accident made it impossible for her to give birth, and Kahlo was forced to make an abortion. In 1932, she conceived again, and this time decided to try and give birth to the child, even if it meant undergoing a Caesarean section. However, this was not to be. Kahlo experienced a miscarriage, losing the child.

She expressed her feelings at this misfortune in the painting Henry Ford Hospital (1932). Other works of the period include the Portrait of Dr. Leo Eloesser (1931), Self-Portrait on the Borderline between Mexico and the United States (1932), New York or My Dress Hangs There (1933) and My Birth (1932). The latter was the beginning of a series of autobiographical paintings describing her early life and heritage.

In 1934, Rivera's commissions in the United States were fulfilled and Calles, who had been the de facto dictator of Mexico, was deposed, and so Rivera and Kahlo went back to Mexico, moving into a small house in San Angel, a suburb of Mexico City. In 1935, Frida discovered that her husband, who had never been too faithful to her, was having an affair with her sister, Christina Kahlo. Extremely hurt by this, she moved out of the house, and even considered filing for a divorce.

The couple got back together at the end of 1935, but their relationship would not be the same. Rivera did not change his ways, and Kahlo started having her own extramarital affairs, both with men and women.

In 1936, Kahlo returned to political activism. She and her husband petitioned the Mexican government to grant asylum to Leon Trotsky, who had just been expelled from Norway because of pressure from Moscow. Mexican President Lazaro Cardenas acceded to the artists' request and in 1937, Trotsky and his wife Natalia Sedova moved in with Kahlo and Rivera, staying until 1939. Trotsky and Kahlo had a brief affair.

It was through Trotsky that Kahlo was introduced to the notable French Surrealist Andre Breton, who was immediately taken with her work, seeing it as a form of "naïve Surrealism […] free from the Freudian symbols and philosophy that obsess the official Surrealist painters." Breton facilitated Kahlo's first exhibition outside of Mexico.

The exhibition took place in 1938, when Kahlo was contacted by Julien Levy, an art dealer from New York. The artist had always painted solely for herself, without giving any thought to an audience, and she did not understand how her artwork could possibly be of interest to anyone. Nevertheless, she agreed to the offer.

The exhibition was a great success. At the time, there were very few art galleries in the United States, and only a handful were dedicated to avant-garde art, so the exhibition received a great deal of attention and press coverage. Out of the 25 paintings exhibited, fully half were sold, and Kahlo received several commissions.

At the time, Kahlo's and Rivera's marriage was once more in difficult straits, and the money that she received did a great deal to help her establish a greater measure of independence from her husband.

In 1939, Frida set out for Paris, at the invitation of Andre Breton, who had promised to arrange another exhibition for her. However, Breton had taken no practical steps towards this goal and after several delays, it was only with the help of Marcel Duchamp, another surrealist, that the exhibition was organized at all.

Kahlo did not like Paris. She found the surrealists and the French public to be "too intellectual" and too snobbish to appreciate the works of a foreign painter, who was, furthermore, female. In addition, Europe was preoccupied with the war that many felt was inevitable, and interest in art was generally low.

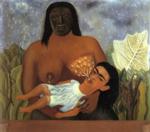

Notable works of these years include the autobiographical My Grandparents, My Parents and I (1936), My Nurse and I or I Suckle (1937) and The Suicide of Dorothy Hale (1938/39).

Kahlo left France immediately after the exhibition and returned to Mexico, where she moved away from her increasingly estranged husband, returning to the home of her parents. The couple officially divorced later that year, mostly at Rivera's insistence.

Kahlo portrayed her despair at the separation in her painting the Two Fridas (1939). However, she was also determined to fend for herself, and this attitude was pictured in the Self-Portrait with Cropped Hair (1940), where she is shown wearing a man's suit and with her hair cut short.

The divorce did not last long, however, and the couple re-married at the end of 1940.

The 1940s saw a boom in Mexico, fueled by the war in Europe, which created a rich market for the country's natural resources. As nationalism surged, Kahlo's popularity in her homeland increased greatly, and she was awarded prizes, invited to join committees and offered teaching positions. She held exhibitions both in Mexico and the United States throughout the period.

In 1942, she was elected a member of the Seminario de Cultura Mexicana, a group whose mission was to promote Mexican culture. In 1943, she was appointed to the staff of the newly founded School of Painting and Sculpture, where she taught a painting class twelve times a week.

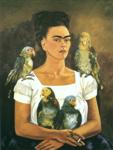

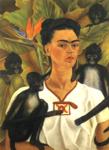

Notable works of this period include Me and My Parrots (1941), Self-Portrait with Monkeys (1943) and Self-Portrait as a Tehuana (1943), all of them exhibiting a pre-Columbian theme.

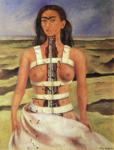

Meanwhile, the artist's health was declining -- a consequence of the terrible accident she had suffered nearly 20 years earlier. The pain in her back confined her to her home, from where she continued to teach, and she was forced to wear a steel corset. She underwent several operations.

This time of suffering is documented lavishly in her works, which include the Broken Column (1944), Tree of Hope, Keep Firm (1946) and The Wounded Deer (1946). Her work of the late 1940s is full of Aztec symbolism, which she linked with the circumstances of her life. A notable example is the Love Embrace of the Universe: the Earth, Myself, Diego and Senor Xolotl (1949).

During the 1950s, Kahlo's health deteriorated steadily. She went through a series of operations on her spine, all to no avail. Eventually, she was confined to a wheel chair, then permanently consigned to bed. She was forced to take painkillers almost constantly, and the technical execution of her work deteriorated visibly.

Some of her last works include Self-Portrait with the Portrait of Dr. Farill (1951; Dr. Farill was the surgeon who operated on her), Marxism Will Give Health to the Sick (1954) and Self-Portrait with Stalin. She also painted numerous still-lifes.

During the summer of 1954, Kahlo contracted pneumonia. She died on 13 July 1954, in the Blue House, the place where she had been born. Her body lay in state at the Palace of Fine Arts in Mexico City, where fellow Communist party members insisted on draping the red flag of their party over the coffin. This provoked a storm of outrage in right-wing newspapers, who called the act a provocation and an attack on Mexican civil society. In accordance with Kahlo's wishes, her body was cremated. The urn was placed in the Blue House, which was converted into a gallery of her work.

Bibliography

The Diary of Frida Kahlo: An Intimate Self-Portrait by Frida Kahlo. Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 2005.

Frida: A Biography of Frida Kahlo by Hayden Herrera. Harper Perennial, 2002.

Frida Kahlo: The Paintings by Hayden Herrera. Harper Perennial, 2002.

I Will Never Forget You...: Frida Kahlo to Nickolas Muray by Salomon Grimberg. Schirmer/Mosel, 2005.

Frida Kahlo: The Painter And Her Work by Helga Prignitz-Poda, Frida Kahlo. Schirmer/Mosel, 2004.

Frida Kahlo 1907-1954: Pain and Passion by Andrea Kettenmann. Taschen, 2000. Biography by Yuri Mataev

- Self-Portrait.

1926. Oil on canvas. 79 x 58 cm Private collection.

- Henry Ford Hospital.

1932. Oil on metal. 31.1 x 39.3 cm. Dolores Olmedo Foundation, Mexico City, Mexico.

- Self-Portrait On The Border Line Between Mexico And The United States.

1932. Oil on metal 31.7 x 35 cm. Private collection.

- My Dress Hangs There.

1933. Oil and collage on Masonite. 45.8 x 50.2 cm. Private collection.

- My Birth.

1932. Oil on metal. 31 x 35 cm. Private collection.

- My Grandparents, My Parents, And I.

1936. Oil and tempera on metal panel. 30.5 x 35 cm. The Museum of Modern Arts, New York, NY, USA.

- My Nurse And I.

1937. Oil on metal. 29.8 x 34.9 cm. Dolores Olmedo Foundation, Mexico City, Mexico.

- The Suicide Of Dorothy Hale.

1939. Oil on masonite. 60.4 x 48.6 cm. The Phoenix Art Museum, Phoenix, AZ, USA. Read Note.

- The Two Fridas.

1939. Oil on canvas. 170 x 170 cm. Museo de Arte Moderno, Mexico City, Mexico.

- Self-Portrait With Cropped Hair.

1940. Oil on canvas 40 x 28 cm. The Museum of Modern Arts, New York, NY, USA.

- Me And My Parrots.

1941. Oil on canvas 81 x 62.2 cm. Private collection.

- Self-Portrait With Monkeys.

1943. Oil on canvas. 81 x 35 cm. Private collection.

- Self-Portrait As A Tehuana.

1943. Oil on masonite. Private collection.

- The Broken Column.

1944. Oil on Masonite. 38.6 x 31 cm Dolores Olmedo Foundation, Mexico City, Mexico.